The Block 2019: Why owner-occupiers, investors and developers are embracing medium-density housing

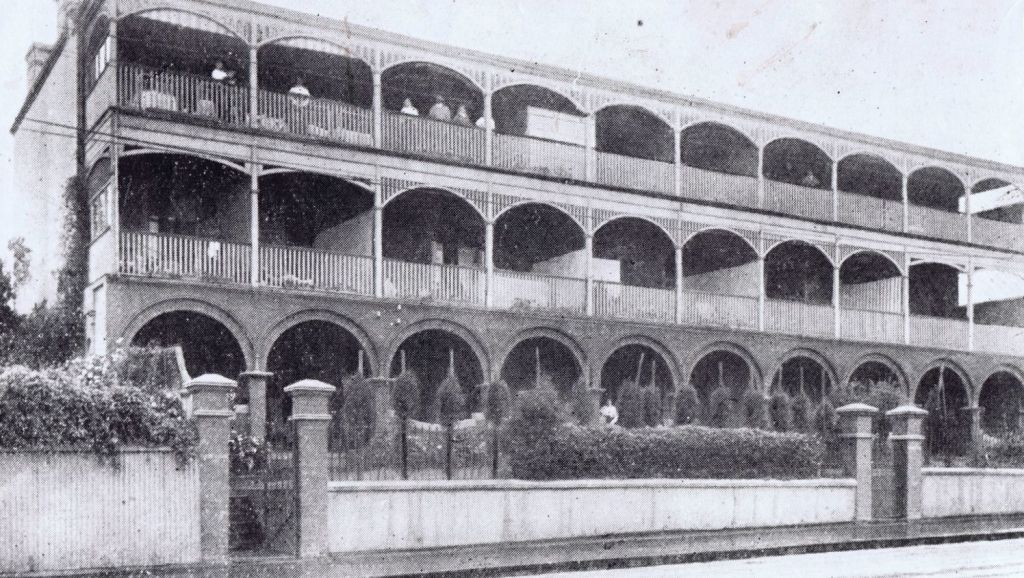

They were originally built in the late 1800s and early 1900s to maximise profit for speculative investors, who bought up inner-city blocks and divided them into skinny lots.

But this old style of housing is back in fashion today both for its relative affordability and the promise of low-maintenance living close to amenities.

Medium-density houses have fallen under the spotlight with The Block’s reveal of this year’s challenge: a row of five terraces that were tucked behind the facade of St Kilda’s Oslo Hotel.

David Mann is general manager development with Metro Property, a company with its sights firmly set on delivering high-quality medium-density housing that will address Australia’s “missing middle”– a term for the lack of medium-density dwellings that sit between free-standing homes and mid to high-rise apartment buildings.

Mann says these dwellings are typically two to three storeys in height, with two to four bedrooms, and front and back gardens or courtyards. There may be a collection of just three dwellings, or as many as 300 dwellings in a development.

“Medium density is where people are living side by side rather than on top of one another,” Mann says, noting the designs and title types are site-specific but can include terraces and townhouses, can be free-standing or with common walls and can be strata title, community title or torrens title.

A change in attitudes

Inadequate design and poor building standards created slum-like conditions in the country’s early terrace housing, which historians say led to many councils banning new terrace development altogether.

Now, government bodies are actively encouraging terraces and other forms of medium-density development, with initiatives like 2017’s The Missing Middle Design Competition, where architects and building designers were asked to showcase their visions for the future of medium-density housing in NSW.

Architect Erhard Rathmayr, co-founder of Brisbane’s Refresh Design, a studio specialising in “urban infill architecture” says the resurgence of medium density has been fuelled by a combination of increasing land prices and “designers who have become more mature to be able to work within the constraints of smaller lots” .

Rathmayr believes a key attraction of terrace housing is its ability to provide “reasonably good density” while at the same time maintaining human scale.

“With a terrace house you lose the setbacks that you get on normal housing but you don’t get the big high-rise block that you get in apartment housing,” he says.

“The owner of a terrace house still feels like they own a house – they have their own identity with a facade, your own front door, you can see your bedroom window, and you have a connection from your parking to your house. But, because they’re sort of glued together, you can get many more dwellings on the same plot than what you get with individual housing.”

Better communities

Daniel Parolek, the American architect who coined the “missing middle” moniker, says medium-density housing supports walkable communities, local retail and public transportation options.

It also creates community through the integration of shared community spaces – an important aspect of this type of housing, writes Parolek in his 2013 paper Missing Middle Housing, particularly within the growing market of single-person households.

Mann says medium-density development allows for better utilisation of costly infrastructure such as water, electricity, roads and rail and while residents may be forgoing land area, they are likely to have access to parks and public open spaces provided by the developer or local council.

Metro Property has built townhouses and terraces across the country and says they have proven popular with a broad demographic, from empty-nesters to upwardly mobile couples who don’t want the maintenance associated with a larger block.

For investors, torrens title terraces may provide more affordability than a free-standing house without the strata levies of an apartment.

Growing demand

Refresh Design has completed projects in Queensland and NSW and Rathmayr says they have been “extremely well-received”.

“Refresh has teamed up with a builder on some of the projects and the first project we did like that – three up-market properties – sold within three weeks,” he says. “We work with light wells or courtyards, so we can get some light into the centre of the plan.”

A return to “rear-loading”, perhaps better known as providing rear lane access, means garages can be moved from front to back with gardens facing the street. Mann says he can see Australia coming full circle, with a return to the Paddington row-terraces so sought after today.

“I think Perth, which has lots of terraces with rear lanes, really started the revival, and a lot of what they’ve done in Perth has been imported to the eastern states,” he says.

For Rathmyr, who hails from Austria, it’s a move towards a European model he’s very familiar with.

“Most Australian cities are dominated by the classic divide between high rise and house,” he says.

“In Europe they settled on [smaller] blocks so that you’ve got a relationship to your neighbour and there’s a social fabric around it. I think Australia would do very well if they develop the missing middle here.”

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More