What you need to know before buying a property in the NSW snowy region

Snow season is upon us, and avid skiers might be wondering whether a mountain property makes financial sense.

After all, peak season rates can be pricy, and regular visitors may prefer putting that money towards a mortgage on their own holiday rental.

Where to buy

Homes in the ski resorts of Perisher Valley and Thredbo are the region’s most expensive, but the prime position means the rental return is higher, and properties are less likely to be vacant throughout the peak season.

At Perisher, expect to pay between $700,000 and $1 million for a two to three-bedroom apartment. A modern three-bedroom chalet at Thredbo costs about $1.3 million.

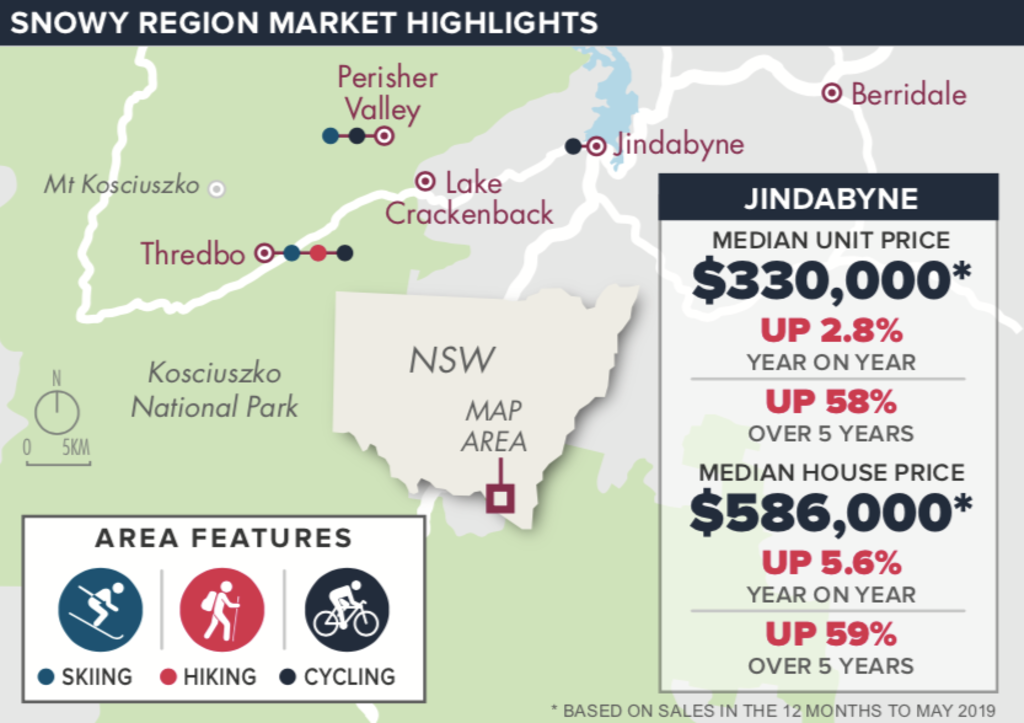

Buyers get more for their money at Jindabyne, about 40 minutes from the snow. Studios start at $200,000, three-bedroom apartments can be found for less than $500,000, and free-standing houses start at about $600,000. Acreage usually costs more than $1 million.

Berridale increasingly draws city buyers due to its affordability, according to local real estate agent Michael Henley of Henley Property Sales. He says a three-bedroom home on a quarter-acre block can be found for about $350,000, but the slopes are an hour away.

What to consider

Before getting carried away, buyers should understand the quirks of resort properties.

Homes within Kosciuszko National Park at Thredbo and Perisher are leasehold rather than freehold. Properties must be used for holiday accommodation, and the typical lease length is 50 years, with most leases expiring in 2057 or 2058.

Securing finance for these properties can be challenging but, according to local agent Michelle Stynes of Forbes Stynes Prestige Property Sales, the premium location is worth the unusual ownership structure.

“If you want to be on snow, you’ve got to be prepared to accept the fact that it’s leasehold,” she says.

Owners of resort properties pay a levy or “bed licence”, which covers upkeep of village facilities. These extra fees eat into profits, says Anna Porter, principal at wealth advisory Suburbanite.

“It can be in the tens of thousands of dollars depending on how many people the property sleeps,” Porter says. “As an investment, they can be very costly to hold.”

Should you invest?

Prices movements tend to follow Sydney and Melbourne, delayed by a few years. This is because buyer activity is often linked to the fortunes of city-based homeowners.

“Snow markets can be very volatile,” Porter says. “When Sydney and Melbourne buyers have wealth to tap into and the market has been strong, they see these opportunities.

“When the market is softer, and their properties aren’t performing as well, they’re less likely to buy into these areas.”

The area relies on winter tourism, lacking traditional growth drivers of a diverse economy, but Stynes says the flourishing mountain biking scene is boosting summer visitation.

Despite the risks, Porter says snow properties may make better holiday homes than beach houses.

“There are only a couple of snowfields in Australia, so there is a limited supply of this type of property,” she says. “Once you get scarcity, you will have a better investment than something that has oversupply issues.”

Holiday homes often aren’t the most profitable financial investments, so buyers should consider snow properties primarily a lifestyle purchase.

While some buyers may have success timing the market, most would be better off buying a high-performing asset and using the income to fund their ski trips.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More

- © 2025, CoStar Group Inc.