Buckle up, Australia: Get ready for a future of room-sharing as renting becomes so expensive

Is the price of rental accommodation in the big cities getting you down? Can’t see how you can afford a roof over your head? Well, in the words of all the least funny people you’ve ever met, “get a room!”

More specifically, get a room that already has other people in it.

Yes, according to a piece by Christian Tietz in The Conversation, room sharing is sharply on the rise in Australia. And while the idea of living with a bunch of other people has historically been most popular with those that join the military or go to prison, most law-abiding civilians find the idea less than appealing.

And that’s not least because the ambience of the typical share-room situation is less “school camp good times” and more “Dickensian slum-hole”.

As with every article moaning about Australia’s housing crisis, the most acute example is Sydney – which is conveniently the city in which this article is part-funding the author’s own exorbitant rent.

If you’re a student or a low-waged worker then there’s a decent chance that your places of employment and study are somewhere in the metropolitan area – where housing is least available and affordable.

So, let’s look at the situation for a student with a part-time job, or someone with an annual income of $39,000 – the after-tax income of a Sydney retail worker on the median salary of $46k a year.

With rental properties in Sydney now sitting on a median of $540 per week, few landlords are going to think your weekly income of $750 makes you a reliable bet. Even a room in a near-city sharehouse is still to cost you around half your salary.

- Related: International students being exploited in Sydney

- Related: Packed to the rafters in problems

- Related: Big data fighting illegal boarding houses

And sure, you could move out into the cheaper, boondockier bits of the outer suburbs, but then you’re opting for fresh problems.

Uni courses are generally strict on attendance, and the lower down the corporate ladder one’s position is, the less flexible employers are about their workers being late for shifts without getting fired. Wear a uniform for your job? Then tardiness is likely to be a punishable offence.

So, since your future ability to eat depends on a high degree of punctuality, how do you plan to never be late if you’re living an hour or more away from work?

Do you budget in the cost of running a car – the sort of reliable, fuel-efficient, never-breaking-down kind of a car that a student or low-income earner might find tricky to afford – day in day out along the city’s majestic toll roads?

Or would you like to bet your employment and/or your degree on the stellar reliability of the public transport in the outer suburbs – especially with the news that the NSW government has just yanked hundreds of millions of dollars from it?

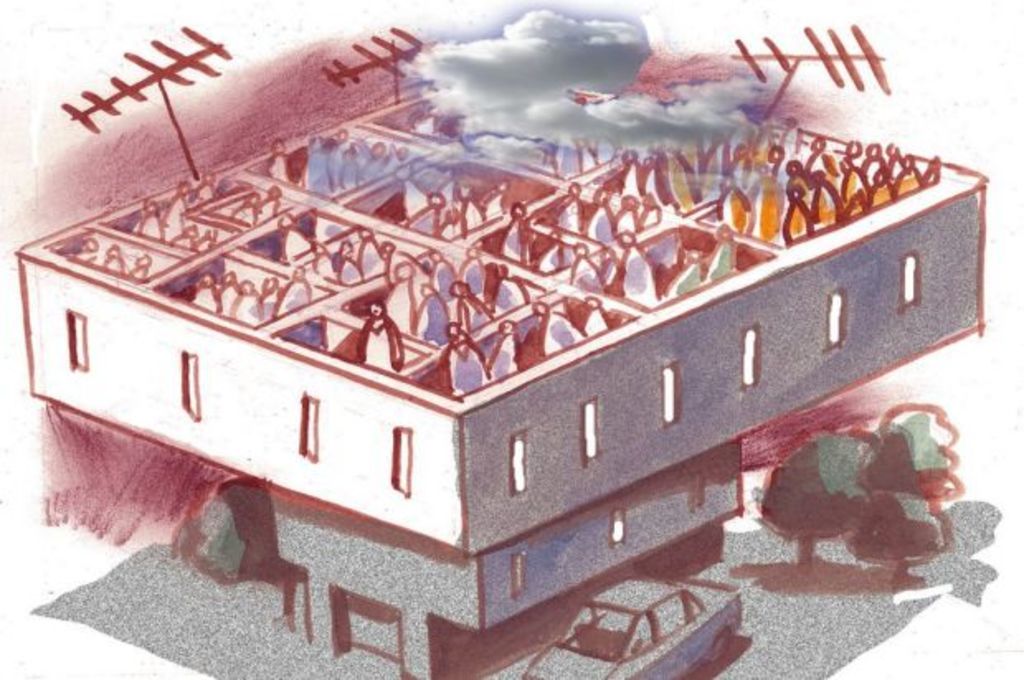

Given these harsh realities, it’s hardly a shock that some inner-city apartments are housing many more people than the number for which they were designed, as people with few options make the best of a lousy infrastructure and rent a bed in a room with other people.

And this causes all sorts of bonus problems for the mattress-tenant. Not just the obvious ones like “where do I put the things I don’t want stolen?” or “how do I dry my towel?” or “so I have to book stairwell time if I want to have uninterrupted sex?”: shoving extra people into limited space puts enormous strain on the systems serving the buildings in which the room-sharing is taking place.

There’s a reason that the bathroom facilities in army barracks are more robust than the typical fixtures one finds in a modern apartment: toilets and showers that can cope perfectly well with one or two people a day don’t function nearly so well serving a dozen.

And that’s before you get into the effects of people living on top of one another, with sinks that can’t cope with all the dishwashing demands, a sewerage system serving double or triple the people for which it was designed, garbage bins filling earlier and earlier in the week, and multiple people breathing the same fetid air of a night.

Sure, nostalgia is a strong emotion, but it’s unlikely that even the most backwards-looking policy maker genuinely hankers for the bacterial romance of the typhoid-riddled tenements of the industrial revolution – yet this seems to be the model our modern cities are seeking to emulate.

But let’s be honest: the return of 18th-century pandemics currently looks more politically palatable than doing anything meaningful about housing affordability like “build affordable housing” or “stop treating housing like an on-shore tax haven for the investing class”. And you’re fully immunised, right? So what’s the problem?

Mind you, it might be best to check your vaccination schedule. After all, now that so many cafes don’t pay their often part-time staff penalty rates they’re probably living in circumst … um, can cholera survive in a latte?

Buckle up, Australia: we might be about to find out!

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More