Could 3D-printed homes solve the housing affordability issue?

For many of us, the concept that a printer is capable of producing three-dimensional objects – let alone entire buildings – is still fairly remote and difficult to grasp.

Yet it would appear that we’re drawing ever closer to a world in which 3D printers build our homes, in as little as three days. There have already been 3D-printed houses constructed in places such as Italy, the Netherlands and the United States, and industry experts say it’s only a matter of time before they become more mainstream.

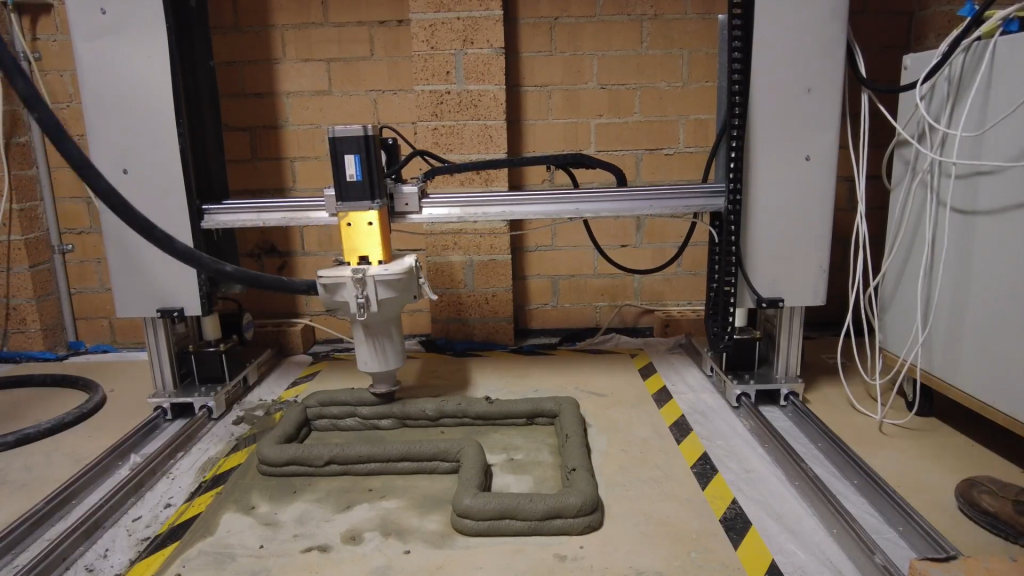

For the uninitiated, 3D printers use digital designs which they construct (or “print”) layer-by-layer, using materials such as concrete, clay or raw earth. Architects come up with the designs, technicians operate the printer and tradespeople fit out the dwelling.

Melbourne group Luyten, who have created the southern hemisphere’s first mobile 3D printer, believe their technology will revolutionise the Australian building industry by drastically reducing construction time and making custom housing more affordable. The 3D printers are particularly good at executing bespoke features like curved walls, for example, which can be a logistical challenge for builders.

“It gives freedom back to the consumer. You will be the decider of how your house looks,” says Luyten CEO and co-founder Ahmed Mahil, who explains that a structure like the Sydney Opera House, which took 10 years to build because of its concrete arches, could theoretically be achieved by a 3D printer in a matter of months.

For University of New South Wales associate professor Hank Haeusler, whose research focuses on using digital technologies in the built environment, the most exciting part of 3D printing is the role it can play in sustainability and climate change.

“Concrete is extremely bad for the environment,” he says. “Everybody talks about how planes are very bad for the environment and cars are very bad for the environment. But the reality is that the construction industry is responsible for a huge amount of waste … that’s really concerning me, and it’s a scandal that nobody talks about it.”

Because of their precision, 3D-printer builds typically produce far less waste and require much less cement than a conventional build. They can also be more easily customised to allow for better ventilation and draft-proofing, meaning they are naturally cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

Haeusler, who teaches computational design, says the biggest challenge when it comes to 3D-printed homes is that architects will need to adapt to a new way of designing – instead of sketching with a pencil, they’ll need to learn to code. His design students are already being prepared for a future of robotics and taught that, in the modern world, “You don’t draw architecture. You program architecture.”

“Twenty-first-century technologies are here, and they’re here to stay,” he says.

Both Haeusler and Luyten have been in talks with housing providers in Western Australian Indigenous communities who are interested in using 3D-printing technology to build affordable, aesthetically pleasing homes. While it’s traditionally been difficult to transport materials and labour to outback locations, a 3D printer might just be the answer.

According to Haeusler, it would also mean these dwellings could be customised to reflect what residents want and need from their homes – including being resistant to cyclones or termites – and create jobs for locals who want to be trained to operate the technology.

So far, Mahil says, several parties interested in using the mobile 3D printer in Western Australia have contacted Luyten. They have also heard from overseas NGOs involved in building affordable housing, a city council in Adelaide exploring the idea of using the technology to construct public furniture, and a south-east Asian company considering whether it might be useful in building bus stops.

When it comes to 3D-printed houses being adopted by the wider Australian community, Haeusler thinks it may take some time for the idea to shift from novel to normal, in the same way that it took a while for the car or television to become mainstream. However, he believes the increasing presence of robotics in building is inevitable.

“That is what we try to teach our students – that these things will change and have changed already, and therefore you need to rethink architectural design,” he says.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More