Making Melbourne: The city's next landmark buildings

Ticking off a handful of what he judges to be among the buildings that established Melbourne as a city of substance, Melbourne University emeritus professor of history Stuart Macintosh says “some, like Parliament House, are obvious; others, like the Queen’s Hall at the State Library of Victoria, are not”.

Macintosh, the immediate past chairman of the august Heritage Council, nominates the elegant 1856 columned space of Queen’s Hall as signalling Melbourne’s emergence as an ambitious, confident state capital – even if it was still young when the glass-ceilinged facility opened as a public library and museum.

“It was one of the few [in the world] of such a scale placed in the very centre of a city,” he says. “Libraries were the way to use wealth to civilize newcomers”.

The newcomers of the age were the tens of thousands of diggers attracted to Victoria’s gold rush.

“Gold transformed Melbourne and allowed the building of our Parliament House on a grander scale than any other in Australia,” Macintosh says. “The Royal Exhibition Building has to be mentioned. The second half of the 19th century was the age of exhibitions, and although it’s not a particularly distinguished Joseph Reed building, this is the only exhibition building left in the world.”

Constructed in 1880-81, “it’s an extraordinary statement of international aspiration”.

“Another great building is William Wardell’s Gothic Revival St Patrick’s Cathedral that took 70 years [from 1858 to 1939] to develop in a combination of bluestone and sandstone,” Macintosh says. “It is more distinguished than St Paul’s Cathedral and remarkably well-sited.”

He says that, with its many church spires and still perceptible hills such as the Spring Street elevation – the rise where the Supreme Court sits – and even Jolimont and Princes hills, “in the late 19th century guidebooks were describing Melbourne as being a city like Rome that is sited on seven hills.

One tower that remains unobscured by the 21st-century high-rise clutter is that belonging to Government House, completed south of the Yarra in 1871. “Modelled in the Italianate style on Queen Victoria’s Osborne House [on the Isle of Wight], it is again beyond the scale of any other Government house in other states,” Macintosh says. “That’s quite extraordinary.”

Turning to residential buildings, he nominates the 1856 row of 10 attached bluestone houses that constitute Royal Terrace on Nicholson Street, Fitzroy.

“There are lots of terraces and, while we didn’t invent them, we did specialise in them. Royal Terrace has a scale and balance to it and was built before verandas and lacework came into use”.

An individual house he nominates is just out of town. Auld Reekie, near the end of Royal Parade in Parkville, is a remarkably intact 1910 Federation Queen Anne villa with all the frills, including a statement belvedere balcony.

Another “extraordinarily fine building” Macintosh knows well is the sublime sandstone Melbourne University residential campus Newman College, designed by Walter Burley Griffin. “Designed before World War I, it is a wonderful, very specific and imaginative work for which Griffin also designed the furniture”.

These structures were all saying, “We are the biggest and the best!” he says. “To the end of the 19th century, Melbourne kept the lead as the thrusting financial and commercial capital of Australia.”

Looking at more recent Melbourne constructions, architect, commentator and presenter of the television programme Restoration Australia, Stuart Harrison contends there are quite a few that argue for Melbourne maintaining the mantle as the nation’s cultural capital.

The first that comes to his mind is “my favourite building and a standout in Melbourne”, Roy Ground’s 1968 National Gallery of Victoria. “So simple but it is a very rich building that takes bluestone and does something different with it,” Harrison says.

Nearby Federation Square (circa 2002) – which is, in his view “Melbourne’s loungeroom” – is another that the founding director of Harrison White Architects nominates as having stood the test of time. “It shows that if you spend the money and do it really well in quality materials, it goes really well.”

ARM or Ashton Raggett McDougall’s two-part redevelopment of the 1934 ziggurat that is the Shrine of Remembrance is admired “as a great piece of work that revitalised a great Melbourne building with four new [semi-subterranean] courtyards”.

“The degree of difficulty of the project was 11,” says Harrison. “How do you work with such a well-known Melbourne building and make it better? But ARM added a whole extra layer to what is already a wonderful building.”

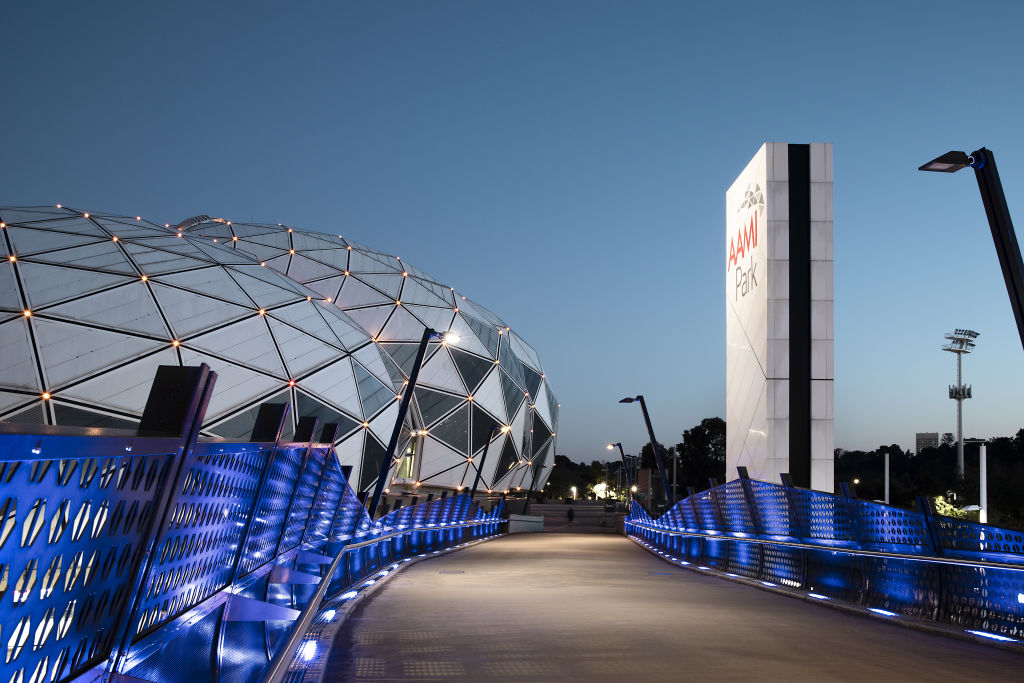

While it wasn’t universally appreciated, the 2010 development of “the big soccer balls”, or geodesic domes, of AAMI Park by Cox Architecture, is, to Harrison, “a great building with terrific digital technology”.

“It’s hard to be inventive with sporting architecture but Melbourne’s first dedicated rectangular stadium is,” he says.

Although the premise of questioning Harrison was to ascertain which of the very recent Melbourne projects he would judge as being worthy of being around in the next century, he admits he is “struggling with the recent completions because there are just so many average multi-residential towers that have gone up.”

The most recent work he will praise is John Wardle Architecture’s sensationally original 2019 music academy, The Ian Potter Southbank Centre.

Considering residential work, he quickly adds Breathe Architecture’s 2014 sustainable multi-residential prototype Brunswick development, The Commons, “as having held up very well and given a whole new identity to that part of the inner city”.

Like Macintyre, Harrison also has to range out of town to name projects of such interest and integrity that they will prevail through the ages.

“It’s not a building but a landscape project by TCL [Taylor Cullity Lethlean], he says. Opened in 2006, the outpost of The Royal Botanic Gardens at Cranbourne “has taken a while but it’s turning into a great contemporary landscape project with some wonderful little buildings within it”.

“It shows that design-led quality ideas and great plantings really do work well,” Harrison says.

Another project “not many people know about” and that they wouldn’t automatically associate with the idea of great Melbourne buildings is Robert Simeoni Architects’ Seaford Lifesaving Club.

“Now 12 years old,” Harrison says, “it is a wonderful timber community building by a wonderful architect that has aged really well. It’s a great example of the kind of buildings we need more of.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More