The Bells Beach Monopoly house built for the bush and the surf

Living deep within bushy hectares close enough to the famous break at Bells Beach on Victoria’s surf coast sounds like an idyllic situation for a medico couple with four kids, and two family members – dad and teenage son – who surf.

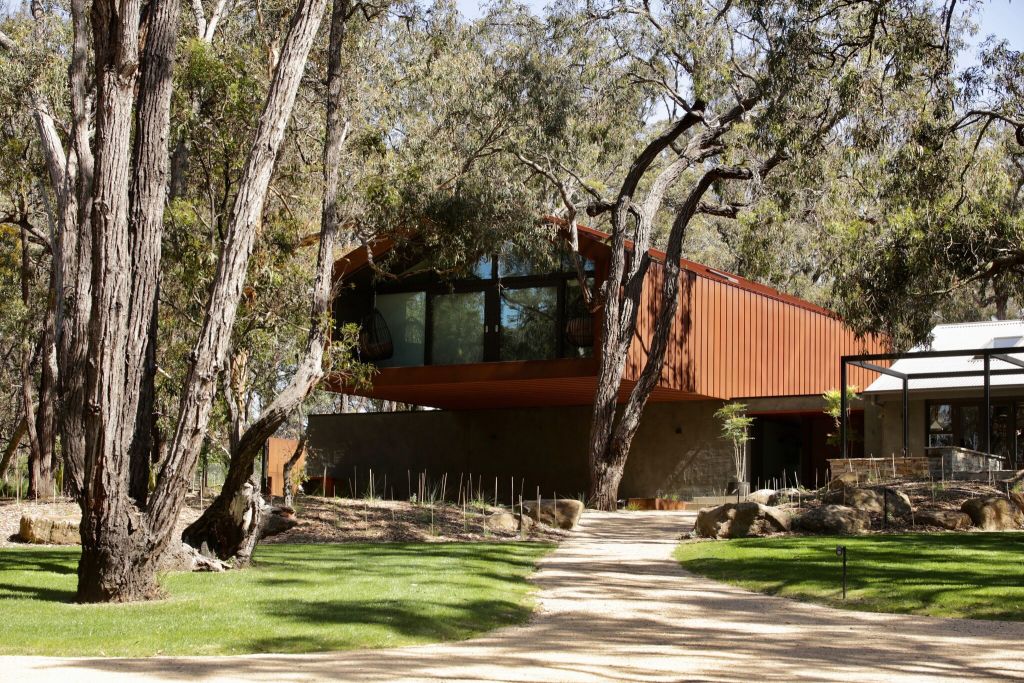

But at Jan Juc, the holiday and downsizer settlement that has prioritised the retention of local plant species, and that on their 2.02-hectare block means many twisty, rutted ironbarks, the reality check for any new build or house extension is defence.

The Surf Coast is high rating bushfire country.

And in light of what our east and south coast Australian summer has delivered to date, this exemplifies thinking, planning and building design that could now become the norm for places located anywhere beyond the kerbed and asphalted suburbs of our capitals.

When the couple came to David Seeley, asking for an extension to a much-amended and rangy 1970s low-rise home, the fire risk study established that the new children’s wing would have a southerly facade with a Bal 29 rating.

In the event … that’s way more than halfway to extremely scary.

And while Seeley, who for decades has been one of the coast’s most ubiquitous architects, claims that the longer he practises the simpler his building forms are becoming, the resulting design for the four bedroom, double-level new wing is so reductionist the upper storey has taken the shape of a Monopoly house.

“Reducing the fire-front concerns was our forefront concern. So the form, which is a version of the existing house, evolved before the material was chosen,” he says.

The material that fully enwraps the cantilevering seven x 16-metre upper level with no eaves or exposed guttering – and that makes such a striking object in the bush garden – is Corten, or tough-as ochre-toned rusting steel.

“We’d considered Colorbond,” Seeley says. “But we put it out for tender and the numbers came in OK for the Corten. And that made it a pretty cool element.”

With a small stair-landing study, two bedrooms and 1.4-metre-wide balconies at each end of the building, the children’s accommodation sits atop of double-brick plinth with some ground-level service rooms and a place where Seeley could create a new entry sequence in a home that previously didn’t have one that could be easily identified.

While ironbark is the hardwood that frames the door, covers the ceiling and makes the stairwell – and is also the stuff of the crafted cupboard joinery in this deeply-recessed and broad entry portal – it’s the 1.4-metre wide and steel-clad “big, heavy door – a really serious door” that is both statement piece and, symbolically, another piece of the house’s fire-prevention armoury.

“I guess, the steel door was a subconscious response to the nature of the property,” Seeley says.

The placement of the children’s wing on an east-west axis was not, he said, the optimal sun arrangement. So on the deck ends, a fully covering mesh of steel serves as balustrade and the supporting structure for future deciduous vines that will keep the bedroom temperate in the hot seasons.

While the six-metre long cantilever is sharp architectural design, it is not gratuitous – rather, “an economic solution to creating car parking. I’m not a big fan of garages.”

Seeley pays compliment to his clients for giving him “enough rope” to make this handsome object. “Because they were so clear about what they wanted”, he could give them back “stripped back architecture in which everything counts and everything solves a problem”.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More

- © 2025, CoStar Group Inc.