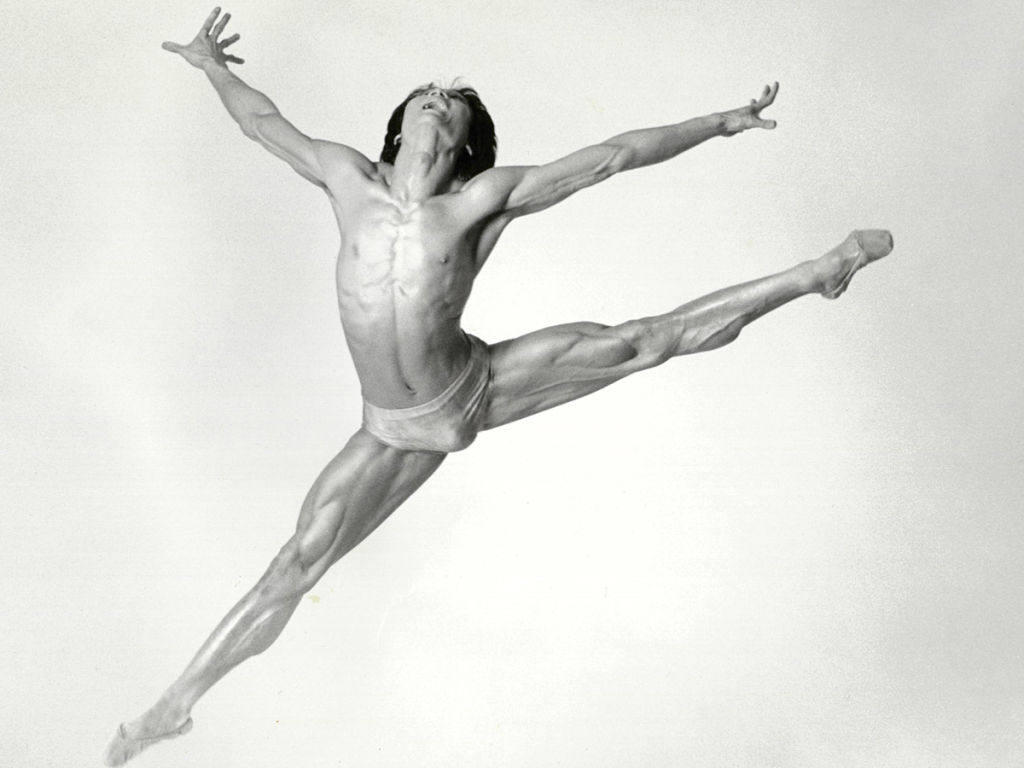

The personal exhibition of Mao's Last Dancer, Li Cunxin, in Melbourne

When internationally renowned ballet dancer, Li Cunxin, who is well-known for his best-selling memoir, Mao’s Last Dancer, first saw the exhibition that tells the story of his extraordinary life, he was moved to tears.

Mao’s Last Dancer the Exhibition: A Portrait of Li Cunxin, at the Immigration Museum, uses photographs, costumes, video footage and other personal items from Li’s archives to paint an incredibly personal picture of his well-documented journey from poverty-stricken rural China to some of the most prestigious ballet theatres in the world. But it was footage of one interview, which Li had never seen before, that caught him by surprise.

“I walked into the room and heard my parents’ voices,” explains Li, whose mother and father are now both deceased.

“It was incredibly emotional for me because it was the first time I had ever heard them say they were proud of me.” While he knew the interview had taken place, he had never seen them on screen.

“Being Chinese in my parents’ era, they didn’t praise their children, so when I heard their words I was in shock and totally overcome with emotion,” says Li, 57, who moved from Melbourne to Brisbane six years ago, where he is the artistic director of the Queensland Ballet.

The interview, he says, is a highlight for him personally, but he singles out other exhibits too. Remarkably, they’re not the awards or costumes that tell the story of his illustrious international ballet career; rather, they are deeply personal items, like a low-to-the-ground, bamboo stool his father used to sit on and tell stories, and a utensil the family used to steam yams.

They are items that transport Li back to the small, dirt-floor hut he shared with his parents and six brothers in rural Shandong, in Mao Zedong’s communist China. Li was just 11 in 1972 when he left home, having been selected by Chinese officials to study at the Beijing Academy of Dance, 1000 kilometres away, despite never having danced before. He was put through a gruelling training regime and was overcome with homesickness, but the chance to support his family financially convinced him to continue.

At the age of 18, Li was awarded a cultural scholarship to the US, to study at the Houston Ballet. In 1981, just days before he was due to return to China, he attempted to defect. Dramatically, Chinese officials held him captive in the Houston consulate for 21 hours. Li won his freedom, but was prevented from visiting his family in China, a ban which caused the dancer years of unimaginable grief and guilt. It was six years before he would see them again.

Fifteen years since the release of his autobiography, he is still surprised that people are so fascinated by his life story. “I never really felt like my life was that special, and it still feels surreal to me that people are so interested in my life.”

- Mao’s Last Dancer the Exhibition is on until October 7 at the Immigration Museum, Melbourne.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More