The case for and against another interest rate rise in May

Updated 26 April 2023

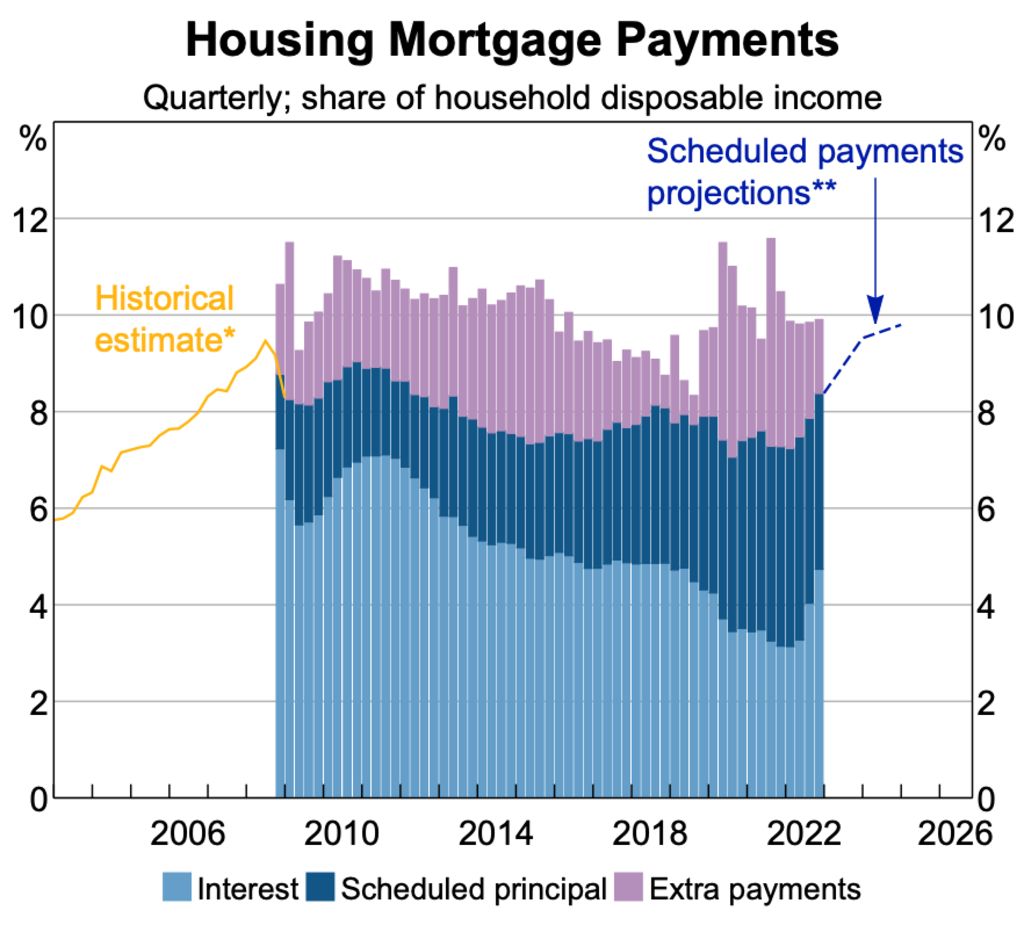

With the pressure from high interest rates building, Australians struggling under the weight of ballooning mortgage repayments will have one key question ahead of the next Reserve Bank of Australia board meeting in May.

Will the RBA keep interest rates steady, or decide that people can handle even higher home loan repayments in the coming months to help bring down inflation?

The millions of home owners who’ve seen their loan repayments go up will be hoping the RBA thinks enough has already been done to get inflation back to its target 2 to 3 per cent range.

In the RBA’s own words, monetary policy is already restrictive, meaning high interest rates are having the desired effect of controlling inflation.

After paying their mortgage or rent and essential expenses, the typical Australian now has a lot less to spend on other things, reducing demand in the economy and helping to bring down prices.

But the RBA made it clear that the purpose of the pause in rate rises was to buy more time to assess the impact of the 3.5 percentage point increase to the cash rate target since May last year.

RBA governor Philip Lowe said after the April board meeting that more rate rises might be needed to bring inflation down, depending on what the next round of data says.

So, what data does the RBA want to see before making its next decision, and what’s the likelihood that rates will stay on hold for longer?

What data will the RBA review before its next decision?

There are several key pieces of information the RBA will analyse before making a decision at the May meeting, the most important of which is inflation data for the March quarter, released by the ABS on Wednesday.

They’ll also be monitoring trends in the labour market, household spending, business conditions and developments in the global economy.

Importantly, the RBA board will also review updated economic forecasts at the May meeting, which will be published in its Statement on Monetary Policy a few days later.

“This suite of additional information would be valuable in reassessing the economic outlook and the extent to which monetary policy would need to be tightened further, especially given the range of uncertainties surrounding the outlook,” minutes from the RBA’s April meeting noted.

The case for another a rate rise in May

While another rate rise in May wouldn’t be a popular move among home owners, some economists think the data will force the RBA’s hand. These are the reasons why the RBA might want to raise rates again.

Inflation hasn’t come down enough yet

Inflation data for the first quarter of 2023 shows the annual rate of inflation has fallen to 7 per cent, down from 7.8 per cent for the December quarter.

Michelle Marquardt, ABS head of prices statistics, said the quarterly rise was the lowest since December 2021.

“While prices continued to rise for most goods and services, many of these increases were smaller than they have been in recent quarters,” she said.

Despite the rate of inflation coming down, Commonwealth Bank head of Australian economics Gareth Aird thinks this result means a 25 basis point rate rise is in May is likely, particularly given the labour market remains very tight.

RBA forecasts from February, based on an assumed cash rate peak of about 3.75 per cent, show inflation returning to the target band by mid-2025. Minutes from the April meeting note that “it would be inconsistent with the board’s mandate for it to tolerate a slower return to target”.

That would imply that the RBA would need to raise rates one more time to keep inflation falling at the rate it wants.

The labour market is still very tight

The latest employment data from the ABS shows the unemployment rate remained steady at a record low of 3.5 per cent, where it’s been for almost a year, with the number of employed people increasing by about 53,000 in march.

“Household finances have been supported by the strong labour market, which has underpinned growth in nominal incomes,” the RBA said in its latest Financial Stability Review.

With the tight labour market putting upward pressure on wages, and incomes forecast to rise, the RBA thinks households will be able to absorb higher repayments. However, that could potentially change as high interest rates continue to slow the economy and strong population growth eases labour shortages, potentially causing unemployment to rise.

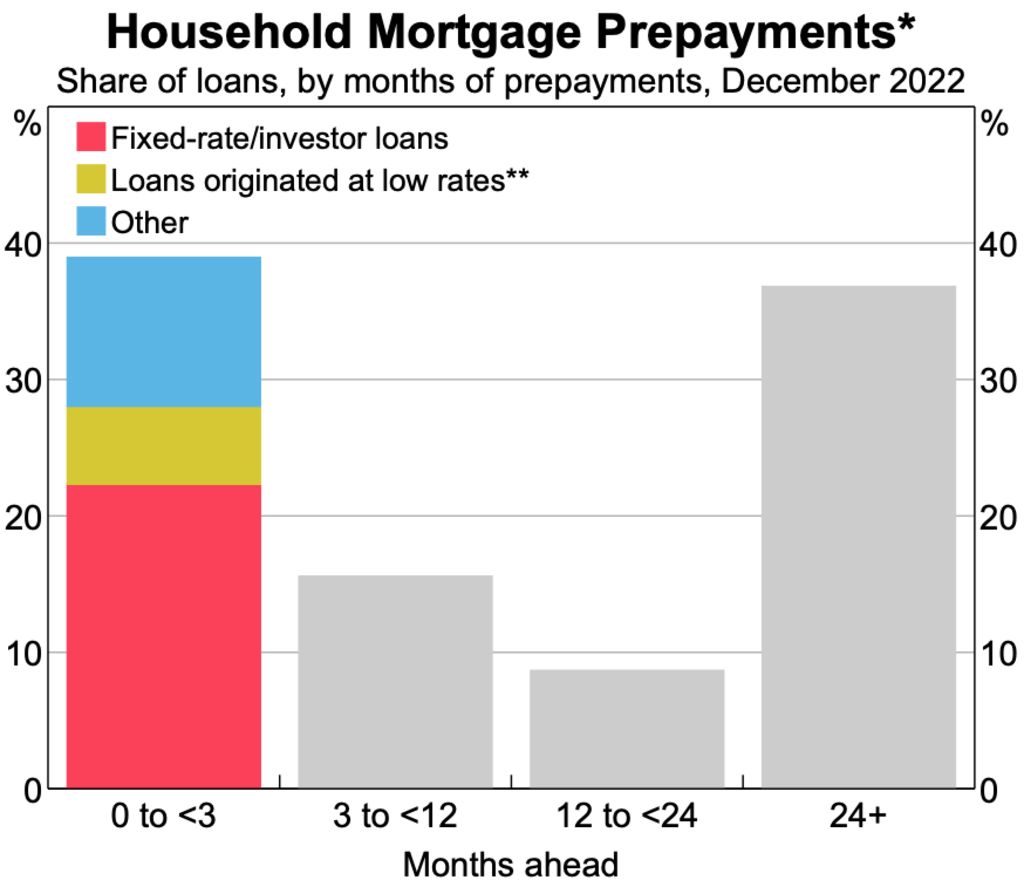

Most borrowers still have plenty of savings to draw on

The RBA says most households and businesses are well placed to manage the impact of higher interest rates and inflation, but concedes that resilience is unevenly spread and some households are already experiencing financial stress, which is likely to continue for some time.

“Indebted households across the income distribution have continued to add to their offset and redraw account balances, particularly those on lower and middle incomes,” the RBA said in its Financial Stability Review.

“In early 2023, more than 60 per cent of all loans had balances in offset and redraw accounts equivalent to more than three months of their scheduled payments and almost half had buffers equivalent to more than a year.”

The case against another rate rise in May

On the flip side, it’s possible that the RBA will continue to leave interest rates on hold at the May meeting. Some economists, such as those at NAB, now predict that the cash rate has already peaked, and the next rate move will be down. Here’s why.

Inflation could fall faster than the RBA has forecast

Although quarterly inflation figures and the monthly indicator show inflation peaked in the final quarter of 2022, ANZ economists believe the effects of high interest rates could be bringing inflation down quicker than expected.

Pausing interest rate rises for just one month isn’t consistent with the RBA’s current stance of taking additional time to assess the impact of rate rises it has delivered so far, said ANZ head of Australian economics Adam Boyton.

However, ANZ still expects one more rate rise in August, predicting inflation won’t fall as much over the June quarter as the RBA would like.

Housing stress is rising

The RBA says almost half of low-income borrowers are now in housing stress – typically defined as spending more than 30 per cent of income on housing costs – as a result of higher interest rates.

“The share of low-income mortgagors devoting more than one-third of their income to servicing their housing loan has increased from around a quarter before the first increase in interest rates in May 2022 to around 45 per cent in January 2023,” the RBA said in its Financial Stability Review.

“There is a group of borrowers who, even if they cut back sharply on non-essential spending, will be at risk of exhausting their savings buffers within six months unless they can make other adjustments to their income or essential spending.”

The RBA says lower income borrowers are over-represented in this group, as well as recent first-home buyers, who tend to have higher levels of debt relative to incomes, and have had less time to build up savings buffers.

Recent data from the ABS shows discretionary spending growth slowed to its lowest level since January last year, meaning people are spending less on luxuries as the cost of essentials, mortgage repayments and rents rise.

The RBA says the proportion of borrowers who are behind on their repayments has already started to increase slightly, albeit from very low levels, and arrears are expected to rise in the months ahead, especially if unemployment goes up.

The full extent of rate rises hasn’t hit yet

The RBA continues to reiterate that monetary policy operates with a lag of a few months, and that households haven’t yet experienced the full extent of rate rises it has delivered.

“Pressures on household budgets will build further as previous increases in the cash rate continue to pass through to variable-rate borrowers,” the RBA’s Financial Stability Review stated.

About a third of borrowers are still on low fixed interest rates set to expire this year and next. They are yet to feel the affect of cash rate rises on their mortgages, and the economy hasn’t yet reacted to the reduction in demand that’s expected when their low rates expire and their repayments rise in line with everyone else’s, reducing their disposable income.

In the RBA’s baseline scenario for the effects of interest rate rises and inflation on households, about 15 per cent of borrowers will experience negative household cash flow by the end of 2023.

That means their mortgage repayments and essential living expenses will exceed their household disposable income, forcing them to draw on savings to service their loans, or if they exhaust their savings buffers, discuss hardship provisions with their lender or sell their property and repay their loan. The RBA says many borrowers are already expected to be in this position.

The RBA’s scenario assumes the cash rate peaks at about 3.75 per cent – 15 basis points higher than it is now – and a higher cash rate than that could have a more adverse effect on household cash flows.

While the RBA appears confident that households as a whole can withstand the financial pain of higher interest rates, by its own admission, this preparedness is not evenly distributed.

Given it’s the most vulnerable households that will be disproportionately affected by a further rate hike, the RBA will need to tread very carefully along its “narrow path” towards a soft landing if it wants to keep Australians in their homes.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More

- © 2025, CoStar Group Inc.