‘A landlord’s market’: Little relief for renters amid tight vacancy rate

Tenants across Australia are struggling to find a place to call home, let alone an affordable property, as rental vacancy rates languish at record lows, new figures show.

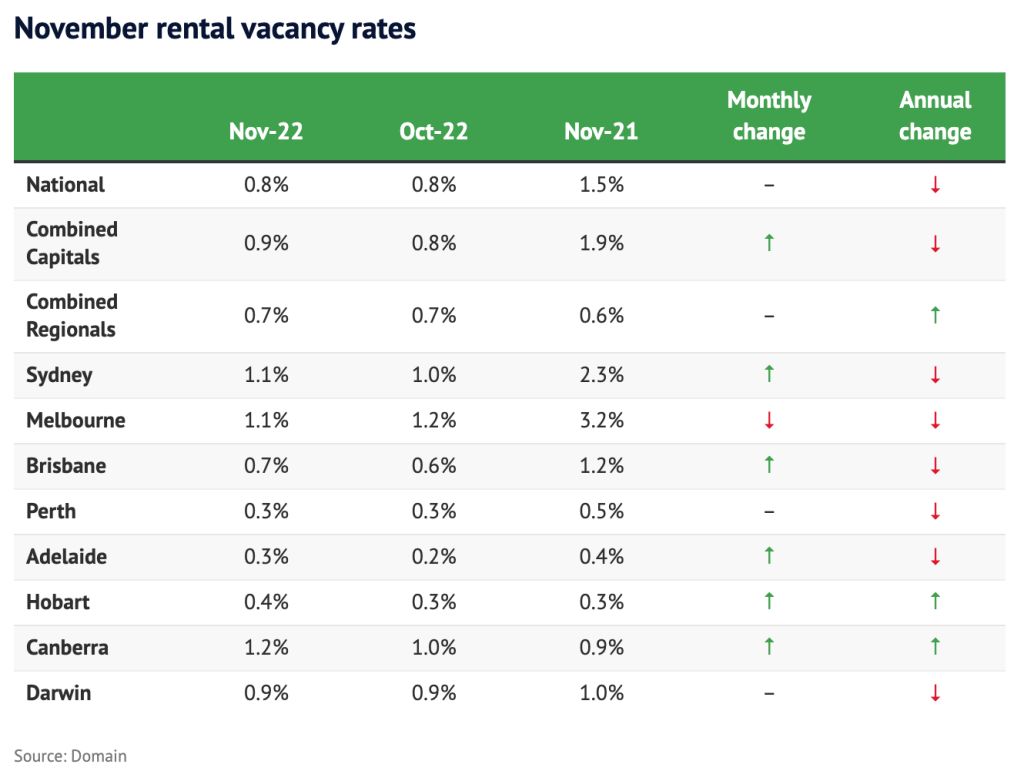

The national rental vacancy rate held at a record low of 0.8 per cent last month, down from 1.5 per cent the previous November, Domain data shows, pushing up competition for available properties.

Vacancy rates held steady or barely improved in most cities and across regional Australia over the month, as the number of vacant properties rose slightly — up 3.1 per cent from October — but experts say tougher conditions could lie ahead for tenants.

Domain chief of research and economics Dr Nicola Powell said this was a seasonal rise as the rental market moved into the busy change-over period, and would do little to improve the situation for renters. While there were about 20,320 vacant rentals last month, that was still down 46.6 per cent compared to the same period a year earlier.

“We still have a landlord’s market across Australia and in every capital city,” she said.

“We’re nowhere near this providing alleviated conditions for tenants. While we see that seasonal lift [in rentals], we also see a higher level of people looking for a rental … it is a drop in the ocean compared to what we need.”

Melbourne was the only city where vacancies declined, slipping back to a record low of 1.1 per cent, and matching Sydney where the vacancy rate inched up from 1 per cent in October. A balanced market is considered to be about 3 per cent.

Perth and Adelaide had the lowest vacancy rate at 0.3 per cent, followed by Hobart at 0.4 per cent. Canberra had the highest rate at 1.2 per cent.

Powell said vacancies were expected to rise over the next couple of months, but could fall in the new year, particularly in Melbourne, as migration picks up and more international students arrive.

She said Melbourne’s inner city — which recorded one of the city’s highest rates at 1.8 per cent — had a dramatic recovery since being hard hit by lockdowns.

Powell said governments needed to make it more affordable to buy a home to ease rental demand, while housing supply should be boosted in middle ring suburbs, more build-to-rent development encouraged, and longer-term leases offered.

Most properties in inner-city Melbourne were leasing within two weeks, said Daniella Ferraro from Harcourts Melbourne City.

Rents were climbing from lockdown lows, and high levels of enquiry had returned, but applications were still on the lower side. However, Ferraro expected that would change as more international students returned.

“[The vacancy rate] will drop further … particularly in certain pockets of the city; the high-rise building areas and those close to universities,” she said. “Those apartments will lease really quickly, and I would say at higher than average rental prices.”

In Sydney, the lowest vacancy rates were in middle and outer areas such as Penrith, Camden, Campbelltown, Bankstown and Sutherland, which all recorded a rate of 0.5 per cent.

Greg Taylor, director of Stanton & Taylor Real Estate, said rental demand in Penrith — more than 50 kilometres west of the CBD — jumped at the start of the pandemic, and had continued since, as more people moved to the area for better affordability.

At the same time, rental supply had reduced, as some landlords cashed out of the market, while other potential investors sat on the sidelines as property prices soared.

Most rentals received multiple applications and were leased within a week, Taylor said, and tenants were increasingly offering to pay more to secure a property.

“People are offering $20 to $50 a week extra, sometimes more, and we’ve had some cases where tenants are offering six months rent in advance,” he said.

Joel Dignam, executive director of tenants advocacy organisation Better Renting, said lower income earners were hit the hardest by the rental shortage.

“There is this funnelling effect, where the people who have the least chance of competing for better properties … are pushed further out, and further down in terms of the quality of properties they’re forced to accept,” he said.

Tenants had been reluctantly handing over bank statements and other private information to avoid missing out on properties, Dignam said. Others felt they had little choice but to engage in rent bidding, which only pushed market rents higher.

“People can’t walk away, they need somewhere to live,” he said.

If governments were serious about improving housing affordability, they had to play a role in regulating rents as part of a suite of tools, Dignam said.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More

- © 2025, CoStar Group Inc.

/http%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2Fafaa350f-dc1a-4931-9797-2604590637b4)

/http%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F87edf59c-5ceb-47cf-b3ca-58f3f764311c)