'Airbnb hotspots' reduce long-term rentals in Sydney and Melbourne, new research finds

Up to one in seven rental properties in Melbourne and Sydney’s most popular suburbs are listed on Airbnb, a new report has found, exacerbating housing affordability in both cities.

The short-term letting platform, under the microscope in the latest Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute report released on Thursday, should be more tightly regulated, according to the authors.

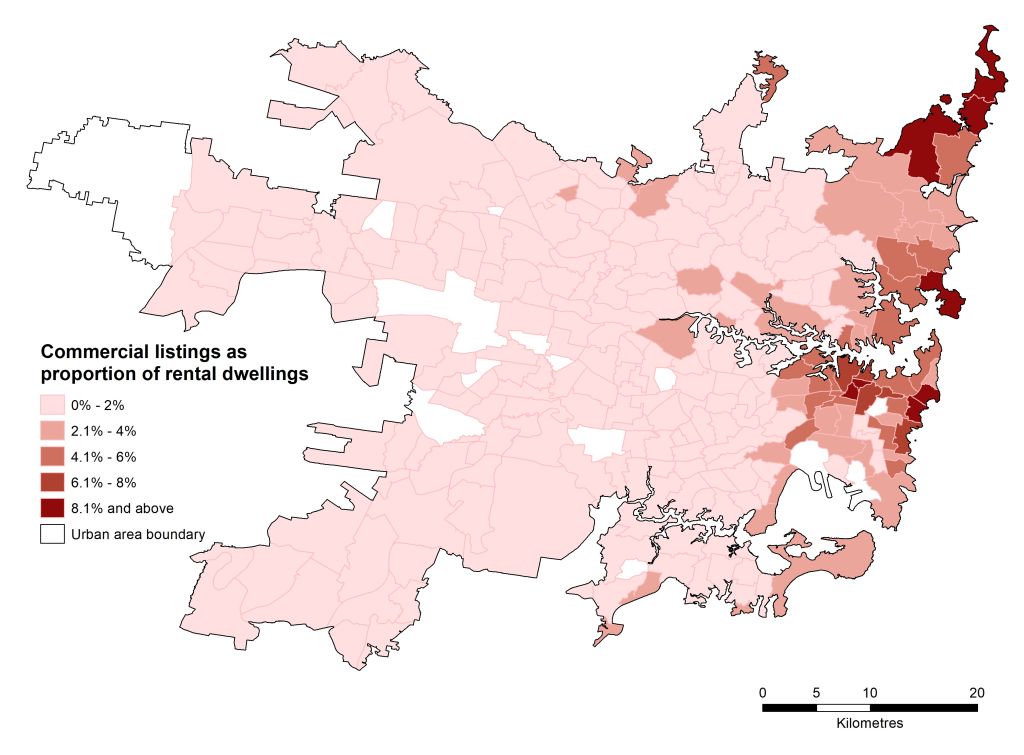

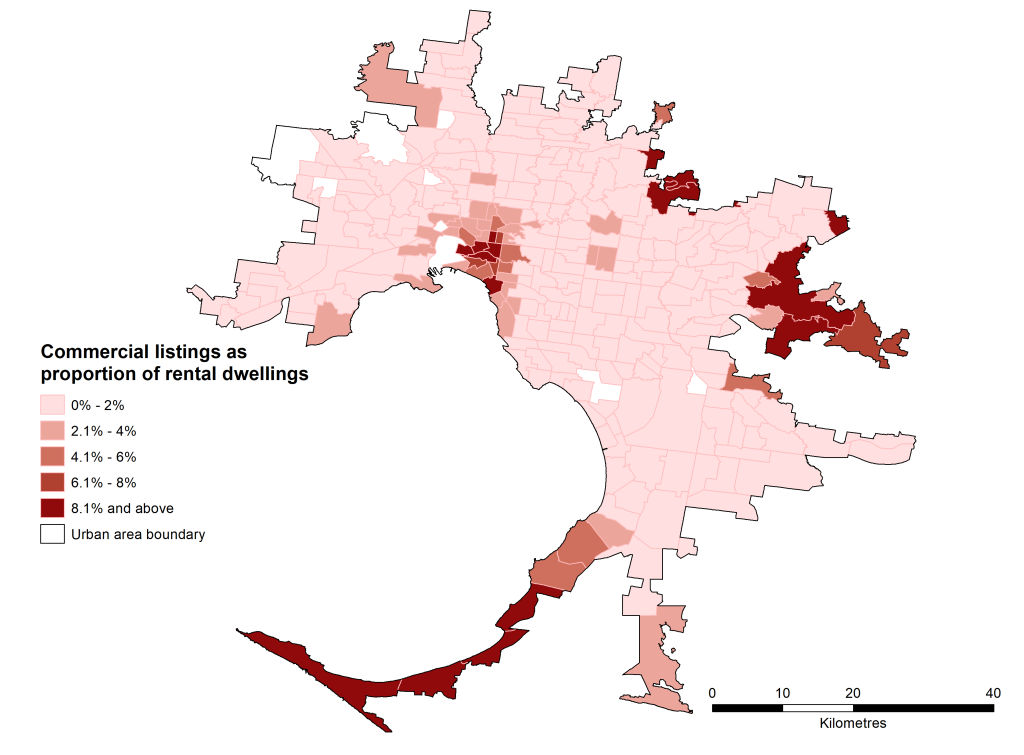

The research institute mapped Airbnb listings in the capital cities, interviewed Airbnb hosts and compared Australian regulations with international rules. It found listings were concentrated in in-demand suburbs, creating Airbnb hotspots that had localised impacts by taking long-term rentals off the market in areas near public transport, employment hubs, essential services and amenities.

In Sydney, commercial Airbnb listings — where an entire dwelling is available for more than 90 days of the year — accounted for between 11.2 per cent and 14.8 per cent of all rental stock.

The concentration was found in the popular eastern suburbs of Bondi, Bronte and Coogee, as well as Darlinghurst and Manly.

In Melbourne, commercial Airbnb listings were concentrated in the CBD, Docklands, Southbank, Fitzroy and St Kilda, accounting for between 8.6 per cent and 15.3 per cent of rental housing stock.

The report identified these Airbnb hotspots and determined their effect by decreasing bond lodgement rates and increasing levels of property vacancy.

“You do see localised impact in the neighbourhoods in the different cities. It tells a story that rental availability is declining while Airbnb is being used an investment property,” said lead researcher Laura Crommelin, from the University of New South Wales.

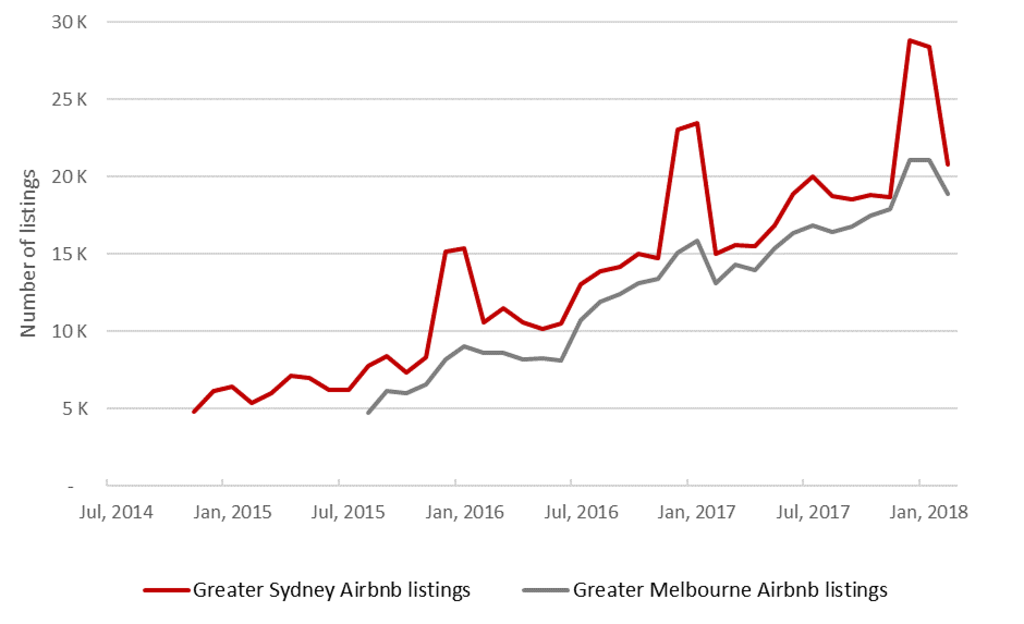

Sydney had 23,121 listings overall as at March this year, with short-term lets sky-rocketing over the summer months. Almost one-third were commercial listings.

Melbourne had 18,838 listings, fluctuating at the same time as in Sydney, but 44 per cent of its listings were commercial.

“There’s more incentive to buy a property and go back and forward to keeping it empty, using it for Airbnb and occasionally using it yourself,” Dr Crommelin said.

Investment property owners were opting to engage in short-term letting because it was more profitable than long-term rental yields, according to the report.

In one interview, an Airbnb property manager explained business had been “growing pretty aggressively” as some investors looked to achieve better returns on short-term letting as house prices dropped.

The report also challenged Airbnb’s oft-quoted mantra that its platform allowed homeowners to cover the cost of local housing pressures. Instead, it found the primary reason hosts listed their properties on Airbnb was for additional income. The next biggest reason was to help cover the cost of owning or renting.

Dr Crommelin said short-term letting platforms were reshaping the Australian housing market as more people considered short-term letting as a viable, flexible and profitable investment strategy.

“It’s another tool that makes property investment more appealing, and those who are already in the housing market make more money off their property,” she said.

Dr Crommelin also said short-term letting regulations in Victoria and NSW were “friendly and generous” compared with cities overseas, where short-term lets are capped at between 30 to 90 days a year.

There is no limit in Victoria, although in August legislation was introduced banning ”party apartments” and fines for unreasonable noise and damage to property.

NSW in June introduced a 180-day cap on short-term lets if the owner did not live there. Neither state government prevents owner-occupiers from renting out their property all year round.

The report concluded short-term letting “helps to reinforce this increasingly inequitable housing landscape in Australia’s largest cities”, contradicting a report commissioned by Airbnb.

Dr Crommelin said a more comprehensive approach was needed to monitor and regulate the industry.

“If we stopped Airbnb tomorrow we wouldn’t solve housing affordability. But it’s not helping the situation either, and the new regulations are good but they don’t go far enough.”

An Airbnb spokesman said the research was fundmentally flawed because the researchers had used second-hand data.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More