Banking royal commission could trigger a credit crunch: UBS

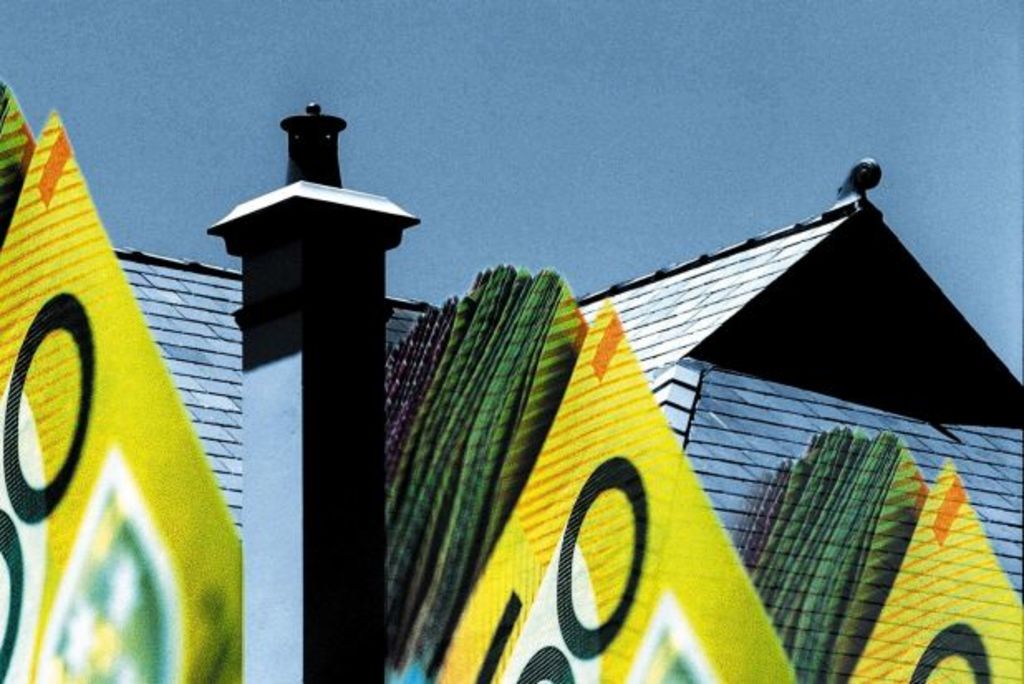

The first round of the banking royal commission held nastier shocks than most expected and the regulatory response could land a significant blow to the economy and house prices, according to UBS economists.

For the past two weeks, Commissioner Kenneth Hayne and several seasoned barristers have questioned key bank executives over questionable lending and sales practices, with evidence of bribery, fraud, failure of internal controls, systemic issues and failures to report misconduct, all heard by the commission.

The regulatory response to such widespread concerns in the banking and financial services space could place the property market in a precarious position.

“While a tightening of mortgage underwriting standards is prudent, especially as the banks move to fully complying with responsible lending, it has a material impact on the economy,” economists George Tharenou and Carlos Cacho wrote in a report to clients on Friday.

“It must be remembered that house prices are determined by the demand and supply of credit (not the demand for and supply of housing).”

As regulators push banks to more thoroughly assess mortgage and credit applications, either a “credit tightening” scenario will play out, or a full “credit crunch” could follow.

Scenario one: credit tightening

A new round of macro-prudential regulation changes aimed at improving lending standards may be handed down, which “could lead to a longer period of sub-trend GDP growth”, the economists wrote.

“A reduction in credit availability and a persistent fall in the flow of home loans would likely cause a larger decline in house prices. This would likely halt the fall in the household savings rate, causing weaker than expected consumption and housing activity (and hence GDP).

“If this negative scenario plays out, the RBA would likely avoid hiking rates for even longer into 2019; and regulators would probably end phase one and two of macroprudential tightening (i.e. caps on investor credit growth and interest-only).”

Scenario two: credit crunch

A crunch would be an unintended consequence, according to UBS, but cannot be ruled out as a potential outcome.

If credit tightening lasts longer than expected it could evolve into a “credit crunch” – defined as a sudden drop in the availability of credit. An economic downturn could follow, involving prolonged falls in house prices across “a few years”.

“This is because the price of money (i.e. record low interest rates) becomes less relevant compared with the supply of money (i.e. credit availability) or demand for money (i.e. employment, income, population) – particularly for the marginal new borrower (especially on lower incomes) which sets the price of the stock of existing housing,” Mr Tharenou and Mr Cacho wrote.

The economists note “a great deal of uncertainty” for an economy that has not seen a recession in almost 30 years and has never seen house prices drop more than 10 per cent, even during the GFC, when prices dropped 8 per cent year-on-year.

“If a credit crunch feeds through to the broader economy and results in rising unemployment, this could see the RBA even consider cutting rates if they became concerned the slowdown was turning into a recession,” UBS wrote.

“In this scenario there is a risk of a pick-up in arrears as existing borrowers become financially stressed, and could precipitate a broad-based credit event.”

Why it’s not time to panic just yet

While debt loads may be high, mortgage serviceability remains strong in Australia, according to veteran chief economist and managing director of Market Economics Stephen Koukoulas.

The ugly revelations from the banking royal commission may not slam into the economy, as UBS predicts.

“Caution is there, but there’s nothing to suggest that there’s any systemic impact on the economy from what’s happened. We don’t have an economic problem and we don’t have a crisis looming anywhere in particular.

“There’s no evidence the ‘liar loans’, as UBS likes to call them, are actually causing a problem for the banks. There’s no evidence of slack lending or slightly dodgy lending has caused anything of concern for the banks because mortgage arrears are so low.”

The Reserve Bank will take a close look at the banking industry’s dirty laundry, according to Mr Koukoulas, but the economy still appears strong despite the new information.

“It’s the job of regulators and central banks and economists to be worried – it’s always in their interests to be saying ‘we’ve got to be aware of the next recession or downturn’ or whatever it happens to be – but for the moment there’s nothing there.

“Interest rates are still very low and people are ahead on their mortgage repayments, if you believe the banks.

“Maybe people not correctly acknowledging what they spend on groceries each week when they were going for their loan – that, to me, doesn’t seem like a major problem.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More

- © 2025, CoStar Group Inc.