Digging holes in Melbourne

Behind a fringe of trees on the Heidelberg-Warrandyte Road at Templestowe is a hole that is so big, it makes the bulldozers pushing dirt around at the bottom appear toy-scale. For 40 years, until the deepest stratum of bluestone was worked out in 2002, it was one of the last of the once numerous metropolitan rock quarries.

Now known as Manningham Quarry, it is progressively being rehabilitated – that is, partially filled up – by operating as a receiving depot for clean fill excavation dirt from Eastern suburbs building projects. Already the back-fill has lifted the level in the crater by about 35 metres. It will take another seven years to make a surface that might become a level playing field or a public open space.

While hard rubbish and suburban garbage has been the usual refill matter, the redeployment of big holes as dumps is what has generally happened to the pits we have been gouging like gophers into the Melbourne landscape since the 1830s.

We flattened Port Melbourne’s sand-dunes for brick sand (and returned night soil – or human manure). We pocked the Southbank claypan for very poor brick clay. (The bricks disintegrated).

We pulled 100 years of bluestone out of the Collingwood Quarry that is now Clifton Hill’s Quarries Park. (It was refilled with garbage). We made the only real island on the Yarra, Herring Island, when the bluestone wall of Richmond Quarry was breached in 1928.

Hawthorn had high quality clay and the recycled, speckled Hawthorn bricks are still in high demand. Geelong, the Mornington Peninsula and Lilydale provided the lime.

The Sandbelt’s ancient dune system that stretches from Cheltenham to Frankston and inland to Clayton, was dug up for builder’s sand. In the 1890s, 15-20 cartloads of sand were daily being dispatched from around Clayton.

While the Diamond Creek and St Andrew’s area is still a subterranean Swiss cheese with some 225 old goldmines – some hundreds of metres deep, no landscape was more exploited than the inner northern suburbs of Brunswick, Northcote and Coburg.

The last was a suburb originally known as Pentridge until the rock-breaking hard labours of the inmates of “Bluestone College”, or Pentridge Prison, gave it too dishonourable an association. Coburg, the name of a Royal lineage, was the classy rechristening.

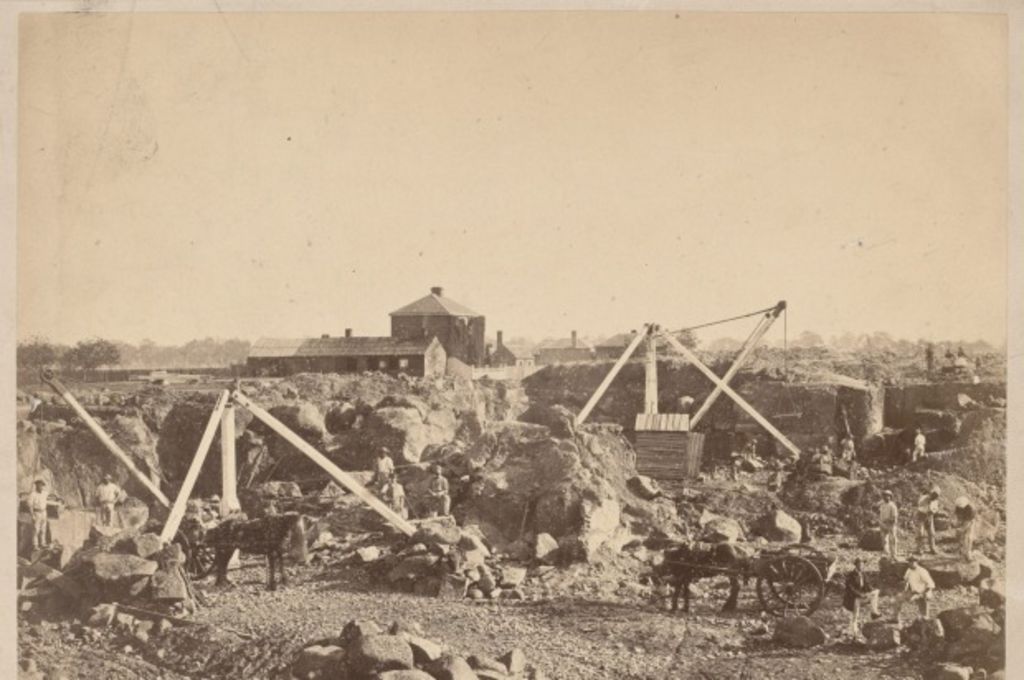

Northcote and Brunswick had terrific clay underfoot. By the early 1860s there were 50 brickyards, with the Hoffman’s outfit employing up to 800 people. By 1865, most of the labourers in the district were working either in brick making, pottery and tile-making, or as quarrymen. By 1875 there were 41 quarries in the creek corridor.

With the Merri Creek in some places having basalt cliff exposures of 20 metres, there were points where bluestone extraction was relatively easy. In other places, such as the Wales Quarry near Albert Street, Brunswick, the digging went way deep.

Over the 100 years that it operated as Victoria’s biggest road stone gravel producer, the Wales operation went down to 51.8 metres.

When the quarry closed in the 1960s, it was taken over by Whelan the Wrecker. The backfill that went into the gigantic wound came from beautiful Victorian buildings on Collins Street and the early industrial factories, the firm was so busily demolishing.

A lot of the red-brick fill that packed the hole beneath the turf of Phillips Reserve had probably emerged from proximate ground as squishy clay. It’s an extreme example of the recycling of building material.

Old Wales Quarry site Melways map 30, B8.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More

- © 2026, CoStar Group Inc.