Fears for endangered species as housing development continues to destroy habitats

Housing development on the fringes of Australia’s cities is destroying hectares of habitats needed for endangered animals, experts warn.

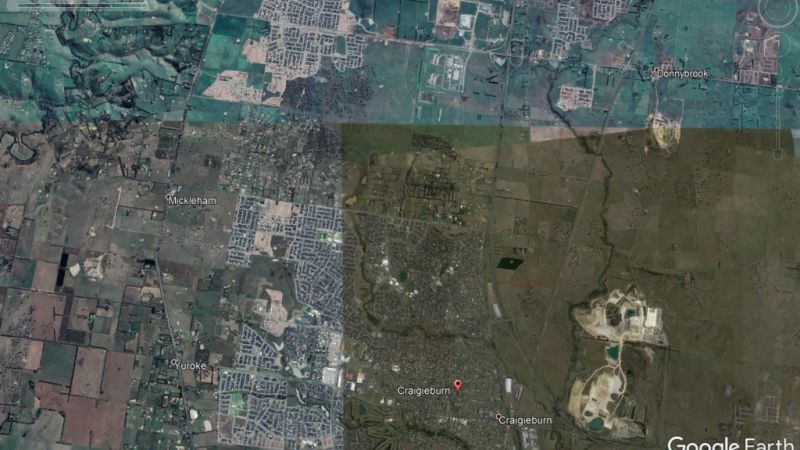

Analysis of satellite images of urbanisation in Harrington Grove in NSW, Craigieburn in Victoria and Springfield in Queensland show hectares of natural habitats eliminated by spread of the cities’ urban footprint.

The destruction puts koalas, quolls and gliders at risk, as well as a menagerie of other species.

Harrington Park in NSW , home to parts of the Cumberland Woodlands, images from Google Earth, 2002 and 2019.

But that wasn’t all, Australian Conservation Foundation’s James Trezise said. Cockatoo populations were at risk in Alkimos, Western Australia, and other species were at risk in Leppington, NSW and Coomera and Undullah in Queensland.

As new suburbs sprung up, they were putting more endangered wildlife at risk, he said.

“When it comes to urban developments and what they mean for threatened species, we’ve seen encroachments around Australia,” Mr Trezise said. “If it’s for koalas in Brisbane or black cockatoos in the Perth region, or critically endangered grasslands in Victoria, they’ve been hit by growing urban footprints.

Springfield in Queensland home to koalas, images from Google Earth in 2000 and 2019.

“People want to know that their new home hasn’t been at the cost of threatened species and the environment.”

While there were protections in place, Mr Trezise said they were inadequate as despite being recognised as significant, bushland could still be cleared.

The Cumberland Woodlands region was almost completely destroyed in Western Sydney, and it was home to dozens of vulnerable species of birds, ground and tree-dwelling mammals and bats.

Leppington in NSW, another patch of the Cumberland Woodlands. Images from Google Earth in 2007 and 2019.

“We’ve run out of patches to protect, and restoring these ecosystems is highly complex so it becomes a critical point in decision-making if we want to protect these ecosystems or enable their continued destruction,” he said.

In Victoria, new development on the city’s northern fringe was destroying one of the rarest ecosystems in Australia, temperate grasslands, RMIT professor Sarah Bekessy said.

“Melbourne has some of the rarest grassland in Australia,” she said. “It’s mostly on private land, it’s mostly in growth corridors.

“Things will be going extinct in times that aren’t too far out unless we change our approaches to managing nature near the inner city.”

Craigieburn in Victoria, images are from Google Earth in 2002 and 2019.

Mr Trezise said there was already one species from the habitat that may be gone.

“The grassland earless dragon hasn’t been seen since the 1960s,” he said. “It could be one of the first reptile extinctions on mainland Australia.”

Professor Bekessy was critical of government projects too, saying the East-West Link would flatten the endangered matted flax lily and remove habitats for other endangered species, and that touted offsets wouldn’t have their intended effect.

“It’s an ecological fallacy,” she said. “You can’t tell an owl living near the Eastern Freeway to fly a couple of hundred kilometres and in a few hundred years there will be a tree for it.

“It just doesn’t make sense!”

Alkimos in Western Australia, images are from Google Earth in 2008 and 2019.

Domain economist Trent Wiltshire said a potential solution was to encourage growth within cities, as opposed to more urban sprawl. He said the benefits were more than just ecological.

“There are environmental benefits, but it also reduces commutes,” he said. “We don’t have to build new infrastructure, we can use existing infrastructure.

“By reducing urban sprawl, people will be closer to a larger selection of jobs, so employers also have a greater pool of workers to choose from.”

This could be achieved through planning rule changes to encourage infill growth, Mr Wiltshire said.

Coomera in Queensland, images are from Google Earth in 2004 and 2017

Mr Trezise said Australia’s biodiversity was increasingly threatened, and change was needed soon.

“Australia already has inadequate environmental protections which has enabled these things to become threatened, if more ‘green tape’ gets cut we’re going to see biodiversity decline at a much faster rate on our urban fringe.

“And we can basically have better planning and have more efficient processes at the same time as development.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More