From bold modernist visions, a future built on hope

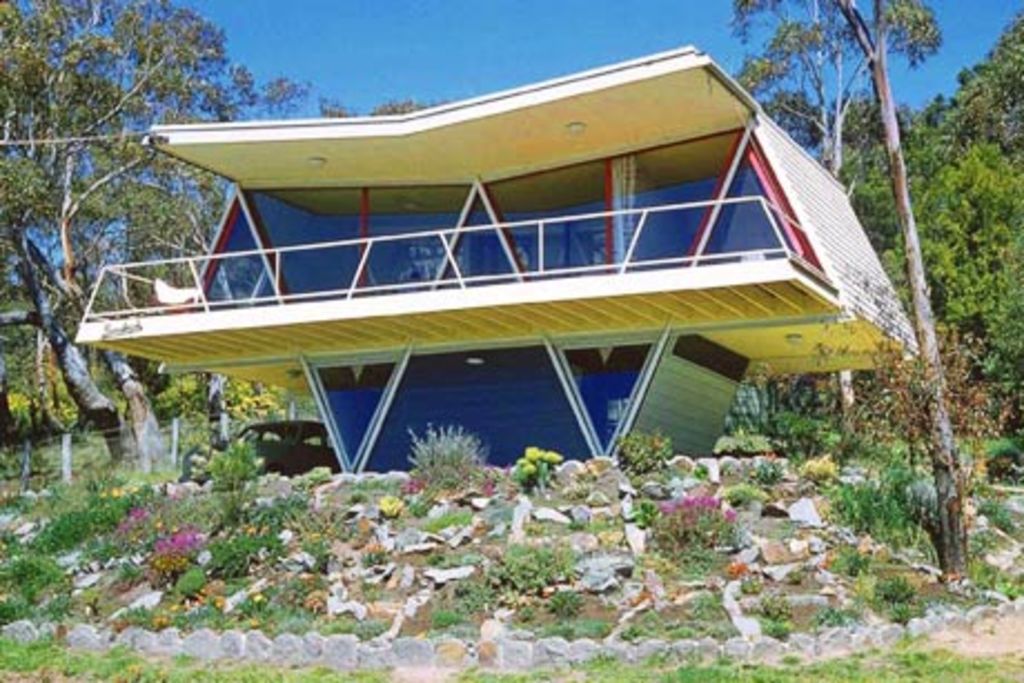

On a Mornington Peninsula still dominated by bush, innovative and eye-catching houses were peeking out from among the tea-trees, evidence of a new design approach that would change the way we live.

In their Frankston office, David Chancellor and Rex Patrick were hard at work, helping to usher in the golden age of Australian architecture.

Melburnians hungry for a bold new style of housing defined by relaxed and open-plan living and the embrace of the outdoors were lining up to commission holiday homes stretching along the bay.

“The peninsula was a rural area that was becoming very popular,” recalls David Chancellor, now 84 and living in country Victoria. “The lifestyle there was more relaxed, and we adopted those thoughts.

We recognised the virtues of the peninsula with the views to the west and the ocean . . . we built in the natural way, sitting the house on the landscape and taking advantage of the views.”

More than 50 years later, on a peninsula unrecognisable from those days, the first survey exhibition of the work of Chancellor and Patrick is about to open. The result of painstaking research by curator Winsome Callister, the exhibition will bring to public attention the distinctive vision of one of Australia’s most innovative but widely forgotten architectural firms.

“Like a lot of architects around Australia, Chancellor and Patrick had dropped out of sight because the focus was on the Sydney school,” says Callister, who came across the firm while studying architecture at Monash University in the 1980s and went on to complete a PhD on their work.

“Chancellor and Patrick were seen as part of the Melbourne avant-garde, with Roy Grounds and Robin Boyd, but particularly with Grounds and his geometric designs,” she says.

“During the ’50s and ’60s, their work was continually published. It was in the architectural journals and Home Beautiful . . . but in the ’70s, with the focus on Sydney, a lot of architects around the country were forgotten.”

Callister’s mission to redress this imbalance began in earnest after David Chancellor asked her to help him find drawings for an exhibition on Edna Walling, whose garden designs accompanied many of the firm’s projects.

Searching through piles of records mouldering under bird droppings and farm dust in his shed, she was overwhelmed by what she found.

“The idea at the start was just to document, to know what was there,” she recalls. “That changed for me later on . . . I thought I could establish something that was permanent.

I actually felt a sort of responsibility that I had discovered this amount of material, and I thought it is so creative, and there is so much of it and no one knows about it.”

Desire and identity, the exhibition that grew out of those first forays into the farm shed, includes photographs and sketches that document a broad creative vision that ranged from the funky “butterfly” house designed for Gerald McCraith in Dromana in 1953, through to boldly geometric suburban homes and public commissions including Frankston Hospital and residential halls at Monash and La Trobe universities.

“I think we were very fortunate in building when we did,” says Chancellor. “In that immediate post-war period, we were all very optimistic, and money was pushed out by the government to get things moving again.”

This sense of optimism emerged as Australians turned their gaze away from Mother England and towards a more energetic America. Labour-saving devices such as automatic washing machines and vacuum cleaners were trumpeted as domestic liberators and the inward-looking houses of the 1940s gave way to open-plan living areas that embraced the outdoors via walls of glass and balconies and courtyards perfect for more informal entertaining.

On the peninsula, and later, in the burgeoning suburbs of Melbourne, Chancellor and Patrick captured this new age in timber and brick constructions whose extended cantilevered roofs and balconies created what Callister refers to as “a real sense of extension out into space”.

“It was unbelievably different to everything in the 1940s,” she says. “Chancellor and Patrick were designing for the climate when other people weren’t and they were designing very much for people . . . In the post-war period, people were wanting something that was human and were feeling that a lot of functionalism was anti-humanist.”

But despite the general mood of possibility, some of the firm’s more avant-garde designs remained little more than lovely ideas committed to sketch pad and then abandoned.

Among the exhibits being shown in Desire and identity is a loose freehand sketch of a multi-circular house initially conceived as the family home of Freda and Martin Freiberg.

Freda Freiberg had fallen in love with one of Chancellor’s Frankston houses and commissioned him to design a family home for her dizzyingly steep block near the Yarra River in Kew. But the couple decided that his “radical” first design was just too impractical.

“One circle was the bedroom wing and another was the living wing and there was kind of a corridor between them,” she recalls. “It was a beautiful piece of sculpture but we thought it would be not very practical for interior decorating. Everything would have had to be specially made.”

Instead, the three-storey home that has since become a landmark of modernist Melbourne is a commanding geometric structure that reaches ever-upwards towards an eyrie-like study overlooking the now towering gums planted by Edna Walling in her first entirely native garden.

Inside, the house is defined by what were then cutting-edge features: exposed brick walls and oregon beams, and a range of unadorned timbers that echo the native palette beyond the glass.

“The outdoors and the indoors relate very nicely to each other, and that was the idea,” says Freiberg.

In 1961 — just a year after the Freibergs moved in — their home was one of 22 included in Best Australian Houses, edited by architect and modernist champion Neil Clerehan. “It was considered quite avant-garde,” says Freiberg, who recalls elderly relatives being shocked by the exposed beams and brickwork.

The perfection of the house’s central brick wall bears witness to the meticulousness of its architect — the first wall was demolished and rebuilt on Chancellor’s orders.

“This was the first time that they had actually exposed bricks, so as far as he was concerned, they had to be perfect,” says Freiberg.

But along with its visual perfection, the house proved robust and flexible enough to accommodate the couple’s growing family of four.

“The house was very good for young children at the different stages of development. Although there were all these stairs, it could be closed off, so it was child-proof,” says Freiberg.

Today, with their children gone, the couple have adapted bedrooms to accommodate office and writing spaces and Freiberg says she has “never wanted to move”.

“Some of our neighbours have moved out as they’ve got older because it’s so hilly. But I love it. I think it’s beautiful and I’m very attached to it.”

Sadly, not all the firm’s projects have fared so well. Time and changing ownership have seen many demolished or altered beyond recognition.

“I don’t want to mention my favourite house, because it has been extended in a most unsympathetic manner,” says Chancellor. “It’s always disappointing when that happens.”

Better then to focus on what he calls the “honour” of the upcoming exhibition.

“Hopefully young architects will get something out of it, and people might go away and think, do I really need four bathrooms and six living rooms?” says Chancellor, a pioneer whose past imaginings offer a vision of how we might live today and beyond.

“Some people think of a house as just a shelter, as somewhere to sleep and be comfortable, but it can be so much more than that,” he says. “A house offers emotional security as well as physical security. We all have emotional needs and I don’t think these are recognised in houses very often.”

Desire and identity: The architecture of Chancellor and Patrick is at the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery, February 16 to April 3.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More