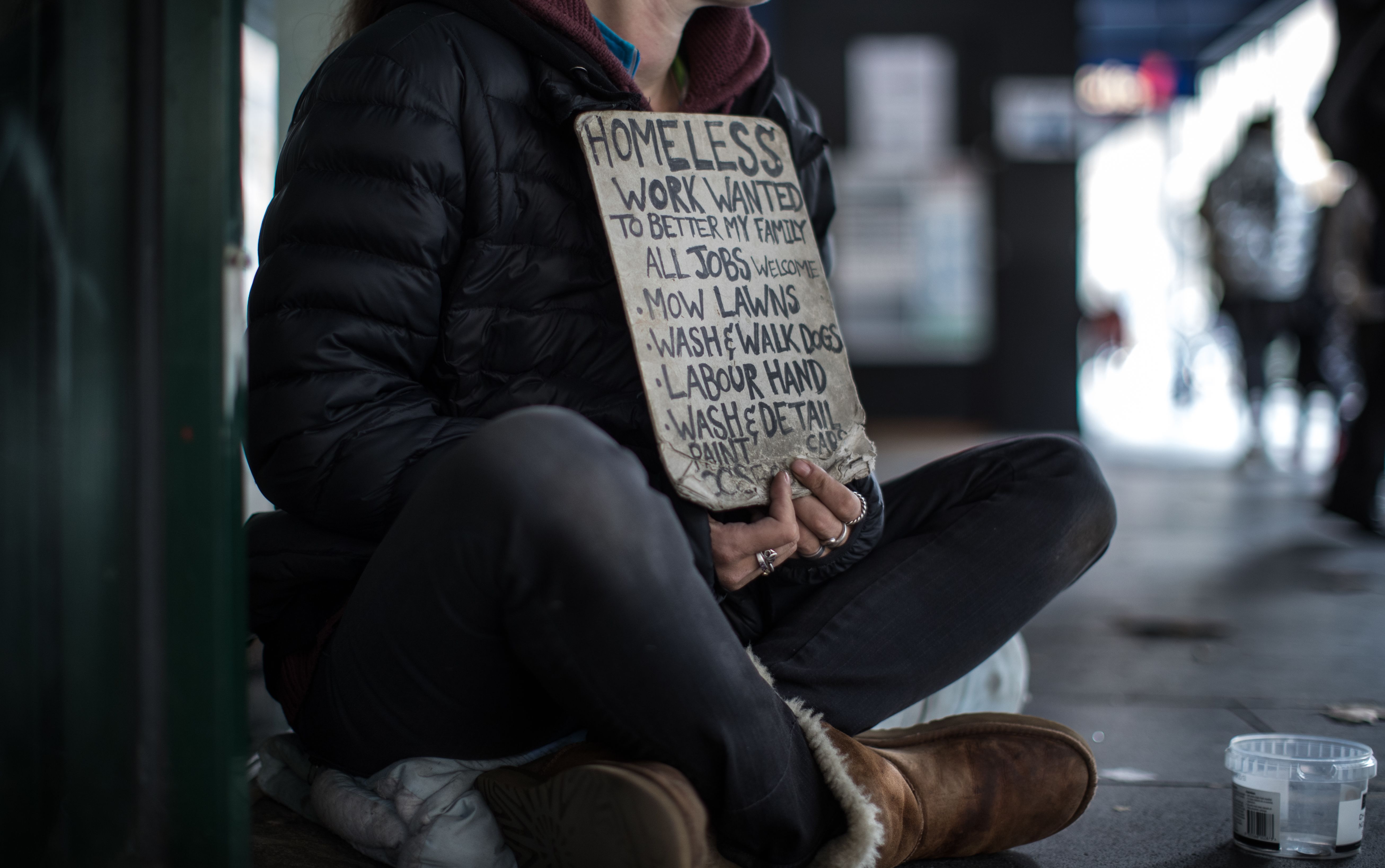

Funds for housing, new laws needed to end homelessness in Australia, say experts

A law to prevent people from becoming homeless, similar to those introduced in Wales four years ago, is one of the bold new ideas being put forward by experts to tackle Australia’s growing crisis.

Such a law would require governments to fund projects that help those at risk of becoming homeless to keep their home while aiding those without a home to find one.

Experts are also calling on the state and the federal governments to join forces to help end homelessness in Australia during Homelessness Week, which runs until August 10.

Australia’s homelessness crisis has worsened in recent years as Australia’s population grows and rents become increasingly out of reach of people on low incomes, particularly in capitals like Sydney and Melbourne.

The latest national statistics from the Census revealed the number of homeless people increased by nearly 5 per cent over the five years to 2016, with 116,000 people experiencing homelessness – 8200 of those sleeping rough.

The number of women aged 55-plus or facing family violence who are seeking help to keep a roof over their heads rose significantly, with homelessness among all women up 9.5 per cent in the five years to 2016, the figures showed.

At the same time, funding for social housing and homelessness services from the federal government has dropped by $82 million in the past five years, according to the Council to Homeless Persons.

So what needs to happen to tackle the crisis facing Australia’s growing homeless population?

Domain spoke to five experts to get their views, all of whom suggested spending more money on social housing.

Jenny Smith, CEO Council to Homeless Persons

Australia could reduce homelessness by adopting laws similar to those used in Wales which legally require governments to deliver prevention support.

That’s the suggestion of Jenny Smith, who has worked with the Council to Homeless Persons since 2011 and is also chair of Homelessness Australia. She said the ideas were prompted by Cardiff University’s Peter Mackie who will speak at a forum on homelessness held on Thursday at RMIT.

In his presentation, Dr Mackie will outline how the homelessness prevention law passed in 2015 in Wales reduced demand for crisis accommodation and shelters and helped more people in crisis keep or find a home.

“Currently in Australia, there is only ad hoc funding for prevention services, with most funding directed to supporting people after they have lost their homes,” Ms Smith said.

“We see policy focus more and more on the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff and ineffective ‘quick fixes’ like shelters, but international evidence shows the most effective strategy is to invest in prevention and social housing,” Ms Smith said.

There is currently a shortfall of 433,000 social housing properties nationally, she said.

“[New laws] would be a game-changer in Australia,” Ms Smith said.

Major Brendan Nottle, Salvation Army

Major Brendan Nottle is a leading voice for homelessness services and job support through his work with the Salvation Army in Melbourne.

He says key issues include the availability and affordability of rental accommodation for people on a low income. Low rental vacancy rates in capital cities and regional areas were significantly adding to the barriers for people to afford to rent.

“It’s not just building homes, but building communities with support for the vulnerable,” he said.

Ensuring there was support for health and mental health for those in need, as well as access to job and skills training was just as important to help people afford to live and pay rent.

Professor Guy Johnson, Urban Housing and Homelessness, RMIT

“What worries me, and has for a while now, is that we have really strong evidence on the most effective way to prevent homelessness, but governments, from both the left and right, continually ignore the evidence,” Professor Guy Johnson said.

Professor Johnson leads the Unison Housing Research Program at RMIT University, which focuses on the issues of housing insecurity and homelessness.

“If governments in Australia actually want to reduce the number of people who experience homelessness they should focus and fund programs that prevent it,” he said.

Professor Johnson said the best way to prevent homelessness was to build more public housing for those in need.

“The evidence we have is unequivocal – public housing is the most powerful factor that prevents homelessness among disadvantaged households,” he said.

Ed Holmes, Unison Housing CEO

Like Professor Johnson, Unison Housing CEO Ed Holmes believes far more funding is needed to build more housing – including social and affordable housing.

“The single, most important factor in preventing and solving homelessness is increasing the supply of social housing,” Mr Holmes said.

Unison Housing works across Victoria and South Australia to connect people at risk of homelessness, or who are rough sleeping, with a short, medium or long-term home.

“We’re certainly in a difficult position; we’re in a crisis.”

Mr Holmes said discussions were being held at a federal level with Infrastructure Australia to include social housing as part of the infrastructure required when new suburbs were being built.

For the first time, housing was being considered as part of Infrastructure Australia’s social infrastructure – assets that contribute to national wellbeing.

“It would be a significant step forward to have social housing considered as infrastructure,” Mr Holmes said.

Kate Colvin, Everybody’s Home campaign spokeswoman

Kate Colvin has worked in policy and advocacy roles for the past 20 years. She agreed more funding was needed to support people who were most at risk of homelessness, including those with more complex needs.

“When people are coming out of hospital with mental health issues they need housing, but they also need support to be able to hold onto that housing and sustain it,” she said.

“There also needs to be action on both preventing and responding to family violence, which is a major driver of homelessness.”

Ms Colvin said governments also needed to consider how people could access jobs and regular incomes to help them to afford rent or ultimately to buy a home.

“One in 10 people coming into homelessness services have no income,” Ms Colvin said. “Some have been breached by Centrelink and lose their Newstart payments.

Others, she said, are unable to access these payments at all. Especially younger people who were born overseas in countries like New Zealand who had lived in Australia for most of their lives, but were not yet citizens.

She encouraged the public to become involved in the Everybody’s Home campaign.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More