Has COVID really caused an exodus from our cities? In fact, moving to the regions is nothing new

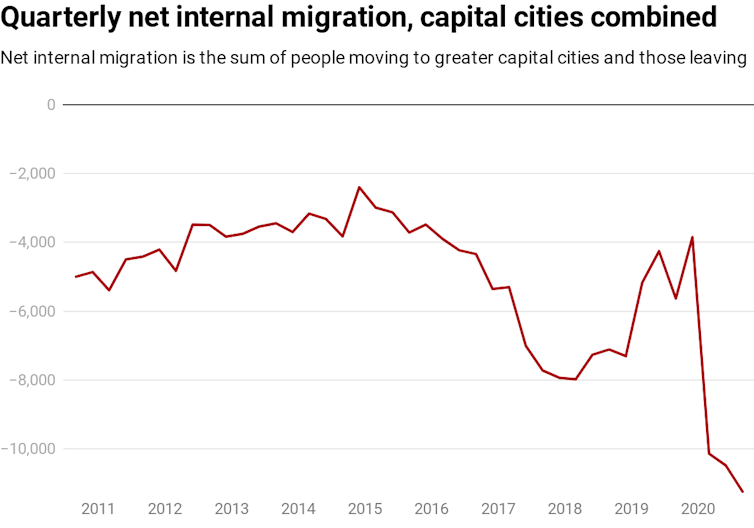

Internal migration resulted in a net loss of 11,200 people from Australia’s capital cities in the September quarter of 2020, according to Australian Bureau of Statistics data released this month.

At the same time, some regional areas experienced significant growth in house prices as demand for properties increased. So this has raised the questions: are we starting to see an exodus from our cities, and is this related to the COVID-19 pandemic?

To work out what is happening there are a few important things to consider.

In Australia we move a lot

The first thing to keep in mind is that Australia has one of the most internally mobile populations in the world. About 40 per cent of the population change their addresses at least once within a five-year period. However, the level of internal migration within Australia has fallen since the 1990s.

Read more:

Australians are moving home less. Why? And does it matter?

The greatest fall has been for long-distance moves between Australia cities and regions, which declined by 25% between 1991 and 2016. Moves between states and territories fell by 16% over this period. An increase or decrease in internal migration from year to year is not unusual.

Putting the numbers into context

While the recent loss of 11,200 people from Australia’s capital cities is the largest on record, it’s not a significant proportion of the population. Australia’s population has grown and so we expect to see the number of internal migrants to grow too.

The net loss of 11,200 people from capital cities is only 0.06% of the total population – 17.2 million – living in these cities. This is comparable to recent years.

While net loss – those arriving less those departing – is interesting, it is also important to consider the actual numbers of people who are moving to or leaving capital cities. The growth in the net loss of population from capital cities in the September quarter was not the result of a city exodus. What happened in 2020 was that fewer people moved into capital cities.

Drilling down further behind the headline data, we find Brisbane, Perth and Darwin all had net population gains. Brisbane has gained residents through internal migration in each quarter since 2014.

The greatest contributor to the recent net quarterly loss of 11,200 was Sydney, with a net loss of 7,782 people. Melbourne was close behind with a net loss of 7,445.

While this might look alarming at first, Sydney and Melbourne are the largest population centres in Australia. And Sydney has recorded a net loss of population through internal migration every quarter for the past two decades. Melbourne recorded net losses until 2012 and then since 2017.

Sydney and Melbourne’s overall population continued to grow over this period due to international migration. Population churn is part of the rhythm of these global cities.

The data also reveal that, on average, regional Australia has been gaining population for many years – decades actually. Moving to regional Australia is not new.

Read more:

Meet the new seachangers: now it’s younger Australians moving out of the big cities

The past year’s COVID-19 restrictions closed Australia’s borders to the previously large numbers of international migrants. Without these international migrants moving to capital cities, the long-term trend of people relocating to urban areas around major cities has become more apparent.

Have the capital cities lost their appeal?

Just considering the September 2020 quarter, nearly 42,000 people moved to capital cities. This is comparable to the March and June quarters of 2020.

This inflow is noteworthy. At a time when many capital cities had mobility restrictions related to COVID-19 in place, people were still moving to these cities. Australia’s capital cities have not lost their appeal.

Data: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Regional internal migration estimates Feb. 2021, CC BY

There is a risk in interpreting net migration from capital cities as an indicator of decreasing satisfaction with city lifestyles or a growing desire for rural lifestyles. It masks the considerable variability in the types of moves people are making, where they are going and why.

Read more:

It seemed like a good idea in lockdown, but is moving to the country right for you?

Outside of capital cities are a whole range of different community types. They range from expansive city areas such as the Gold Coast and Geelong through to tiny agricultural and fishing hamlets.

The fastest-growing areas outside capital cities are those that offer sophisticated urban settings. They have diverse employment options and high-order social, education and healthcare infrastructure. So when people leave a capital city, more often than not they are moving to a large city.

Will COVID-19 lead to growth in smaller centres?

Australia’s overall population growth has promoted the growth of capital cities and larger regional cities. Some smaller communities, particularly high-amenity coastal towns, have also experienced periods of sustained population growth.

Distributing this growth further inland to smaller towns and cities is both possible and plausible.

A major barrier to population growth in smaller rural communities is the lack of diverse local employment options. For those who have made the transition to working fully or partially online as a result of COVID-19 restrictions, moving further from their workplace more permanently – and perhaps to the country – could be on the cards.

Read more:

More urban sprawl while jobs cluster: working from home will reshape the nation

So is there a pandemic-related exodus?

The COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting the way we live our lives but, no, there is not an exodus from Australia’s capital cities. For some, pandemic-related disruptions might have heightened their dissatisfaction with where they live. For others, working from home might have provided them with the opportunity to consider alternative living arrangements.

However, right now, given the data we have, it is unlikely that COVID-19 is driving a shift away from capital cities or city lifestyles.![]()

Amanda Davies, Professor of Human Geography, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More