Healthy, happy and tropical – the world's fastest-growing cities demand our attention

What does it take to be a happy and healthy city? In any city, myriad factors go into the mix – and of course we are not dealing with just one kind of city.

But, due to the world history of colonisation, models are still too often European-centric. In particular, we need to adjust how we think about cities in the tropics.

For a start, almost half of the world’s population lives in the tropics and more than half of the world’s children. This makes it the fastest-growing region on the planet. The pace of economic and technological development is fastest in the tropics, too.

The tropics are also home to the greatest diversity of architectural styles and urban places. Sandwiched between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, nearly 50 countries display singular tropical urbanism, which reflects first settlements, colonial history and the more friendly contact with other cultures.

Nowhere else on Earth can we see such a mingling of vernacular, pre-Columbian, Gothic, Baroque, Renaissance and Modernist buildings and urban plans.

Designing for the tropics differs considerably from designing for temperate areas. The climate can be very hot and humid, causing extreme discomfort for city residents.

Of course, they too aspire to the good health and well-being that have been promoted as being at the heart of urbanisation from the 18th-century hygienists onwards. Sustainable development entered the picture in the 20th century – the 1987 Brundtland Report coined the term.

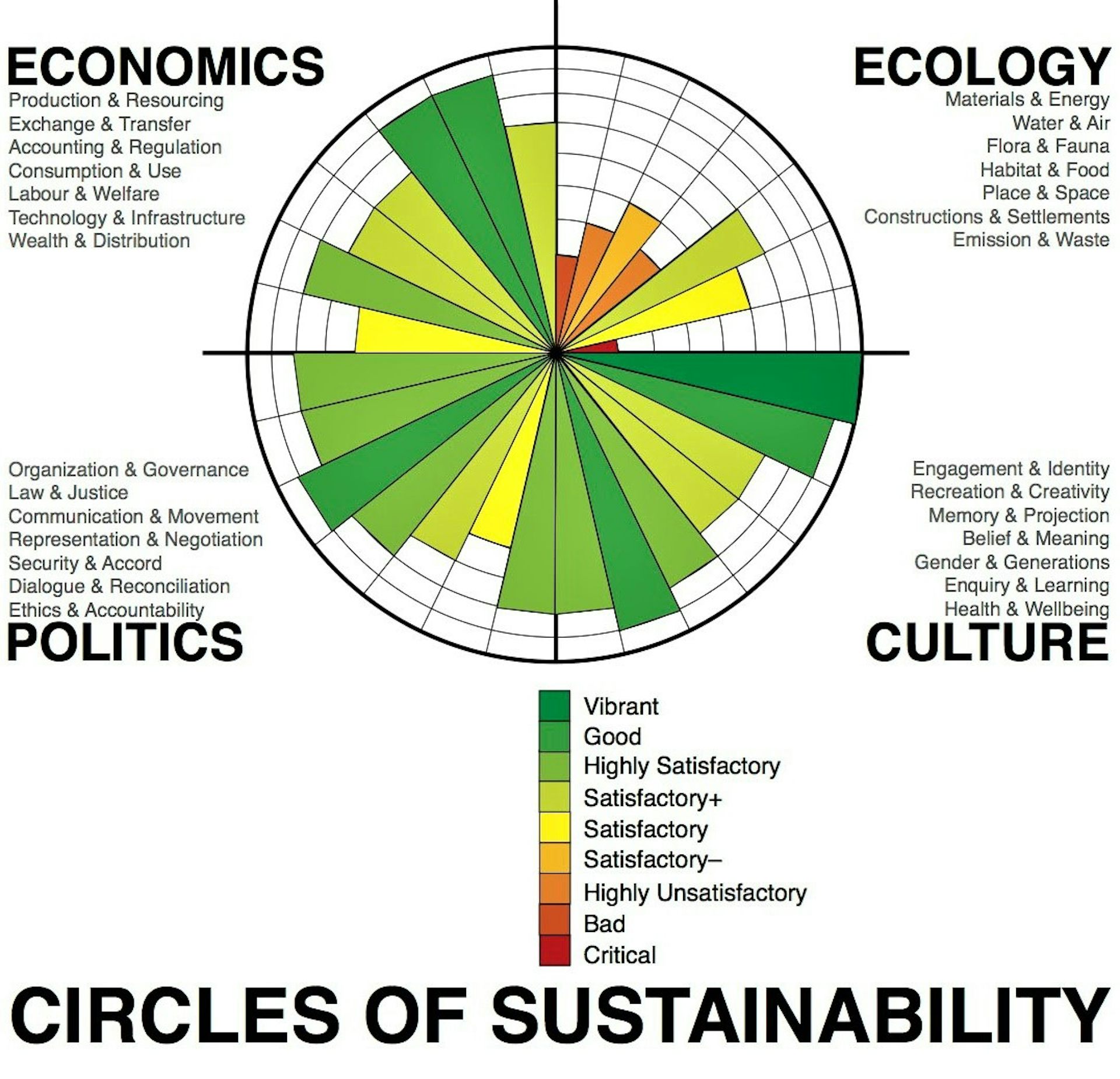

Paul James took sustainable development beyond the original social-economic-environmental triad with the circles of sustainability. This draws attention to other significant elements, including culture (e.g. creativity, belief and meaning, etc.) and politics (e.g. organisation and governance, dialogue and reconciliation, etc.).

Paul James developed the concept of circles of sustainability that incorporate elements of politics and culture (this one represents Melbourne in 2011).

SaintGeorgeIV/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

How do cities achieve all these goals?

With the prominence of good health and well-being in the New Urban Agenda and UN Sustainable Development Goals, cities are paying more attention to well-being and happiness indexes and reports.

So how exactly can urban design and experience design – the design of how the visitor will live, appreciate and remember the place – enhance well-being and happiness in the world’s growing cities?

The Healthy Happy Cities in Tropical Environment (HHCTE) network was founded in 2018 to investigate these questions and report on best practices, as well as providing for critical exchange through workshops and conferences.

Recently, at the inaugural two-day HHCTE workshop, urban researchers, professionals, civil society actors and decision-makers came together to identify challenges in achieving happy healthy cities in tropical environments and to propose solutions. Several significant findings emerged.

Firstly, and very fortunately, we can learn from many examples of best practice in urban design all around the world. These range from free public open-air swimming pools (e.g. in Cairns and Brisbane, both in Australia) to Gardens by the Bay in Singapore and Mumbai Marine Drive in India.

However, when prompted to identify and describe the processes and principles that delivered such successful urban designs, HHCTE participants articulated very few of these clearly. This can partly explain why we so often face problems with transferring models or principles (besides the change of context, local features, etc.).

It demonstrates how the understanding of experiences might be difficult to access and express. This sort of communication needs to be developed.

Second, we all come with bias. Our cultural background might determine, for example, whether it is important to have free or consumption-based urban experiences. For instance, for some the quality of shading and sitting areas through the journey from one place to another might be plenty, while for others the opening of a bright new shopping mall might symbolise a great urban experience.

The idea that urban design should cater for multicultural diversity is not new, but the emphasis on money-based urban experiences raises questions about the role and meaningfulness of public spaces. Is this a shift from our traditional paradigm?

Third, when asked “what makes you feel happy and healthy in the city?”, all groups of participants, without exception, mentioned ease of walking, bike paths, greenery, public transport and safety. These urban infrastructures really do matter for everyone.

But then, surprisingly, all participants seemed to don their urban designer hats and forgot to express their more personal feelings. The aim seemed to be to use a neutral vocabulary, as well as trying to reach a professional identity and consensus. Yet, when back home, will everyone not dream about something else – such as colours, music, smells, urban atmosphere and so forth – for the city they live in?

What next?

The main aim of participation workshops is to give voice to a variety of stakeholders and engage in bottom-up actions that lead to improvements. While we need to be aware of the pitfalls of participation, such as unbalanced processes, it remains a great tool to take the pulse of one society.

On the specific topic of healthy happy cities, the workshop again demonstrated that citizens have good ideas and are ready to be engaged. Yet it also showed that the broad city scale of the discussion influenced the proposals. Perhaps a discussion at the level of the house or street scales would have been closer to the heart of each participant.

We also learned it takes many little steps and aspirations to become a happy healthy city, all of which are feasible. What, then, are we waiting for?![]()

Karine Dupré, Associate Professor in Architecture, Griffith University; Jane Coulon, Lecturer, School of Architecture, Reunion branch, École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Montpellier, and Silvia Tavares, Lecturer in Urban Design, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More