House prices to rise 22 per cent this year, and grow further next: Westpac

Westpac has tipped property prices to rise by more than 20 per cent this year, increasing its price forecast yet again as the market continues to boom despite extended lockdowns.

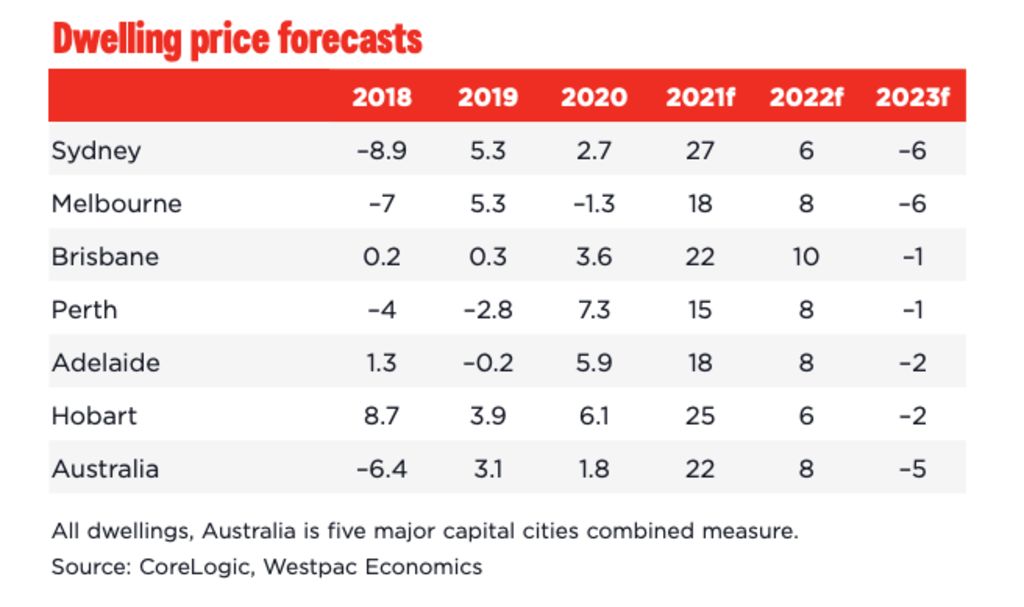

The bank expects property prices to climb 22 per cent this year, up from a forecast of 18 per cent, and has also lifted its outlook for next year from 5 to 8 per cent.

However, it has warned the property boom is entering trickier territory, with a correction expected from 2023.

Senior economist Matthew Hassan said the property market, fuelled by record low-interest rates, had blasted past price expectations – going well above earlier forecasts for 15 per cent growth this year – with only a slight dampening effect from the latest COVID lockdowns.

Prices rose across the country another 1.5 per cent in September, taking the nation’s median dwelling price to almost $675,000, according to the latest CoreLogic figures. Values are up 17.6 per cent since January, and more than 20 per cent over the past year, marking the fastest annual growth seen since 1989.

Mr Hassan expects prices in Sydney to jump 27 per cent before the end of the year, with values in Brisbane and Hobart also expected to climb more than 20 per cent. Annual price growth of 18 per cent is forecast for Adelaide and Melbourne, and 15 per cent growth is tipped for Perth.

ANZ also expects national growth of more than 20 per cent, revising its forecasts upwards in recent months, while CBA increased its forecasts to 20 per cent, and NAB forecast 18.5 per cent growth back in July.

Westpac’s increased forecasts come after the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) announced banks had to lift the buffer rate applied to loan serviceability assessments from 2.5 to 3 per cent, which is estimated to reduce maximum loan sizes by about 5 per cent.

The move came earlier than expected, Mr Hassan said, though he felt its impact on the market would be marginal, given more than 80 per cent of borrowers were not taking out the maximum loan size available. However further tightening of lending restrictions, such as a crackdown on high debt to income ratios, may have a bit more of an impact – particularly on investors with multiple properties.

Still, he expected investor activity to lift from its comparatively subdued levels – accounting for just 25 per of the value of loans over the last 12 months, compared to close 40 per cent over loans over 2015-17 – as affordability constraints squeezed out owner-occupiers.

“That is the real risk factor for the market. The investor segment has been pretty subdued throughout the boom so far… but if there’s a segment that’s going to sustain the boom for longer it’s likely to be investors,” he said, which could drive more persistent price gains near term but also result in a more material correction.

“This is the pointy end of the price cycle, where affordability strains start to price people out of the market altogether, and even if you do have investors coming in in a big way that’s a riskier environment in terms of sustainability in price gains and the tolerance of regulator. We are getting into much trickier territory and the policy side of things is now in play.”

Already, the Sydney and Melbourne markets are 18 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively, above their previous price peaks in 2017-18, a time when both had major affordability problems.

Mr Hassan expects the market to have run out of steam by 2023, forecasting a pullback of 5 per cent as official interest rates rise – though the Reserve Bank still has the first cash rate hike pegged for 2024.

“Even though rates will still be low, it’s about the shift in the direction …the sentiment will be that there is no more scope for [rapid] price growth … and I think that will be the thing that tips us over into a correction,” he said.

Dwelling completions, at a time of low population growth, could also weigh on prices, he added, with more than 200,000 dwellings completed this year – more than double the increase required with slower populating growth.

Oversupply had so far been limited to certain pockets, given the prolonged period of underbuilding that proceeded the latest building cycle, but that may shift if the return to significant net migration inflows takes several years to come through.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More