Housing affordability already declining across the nation, on the cusp of being 'obliterated'

Housing affordability is back on the decline across Australia and could be “obliterated” by surging property prices, a new report shows.

Rapidly rising house prices and larger homes loans saw a deterioration in housing affordability last quarter, according to the Real Estate Institute of Australia’s (REIA) latest Housing Affordability Report, released Wednesday.

Nationally, the report’s measure for housing affordability — the proportion of income required to meet loan repayments — increased 0.9 percentage points to 34.8 per cent over the December quarter, just months after the nation entered its first recession in almost 30 years.

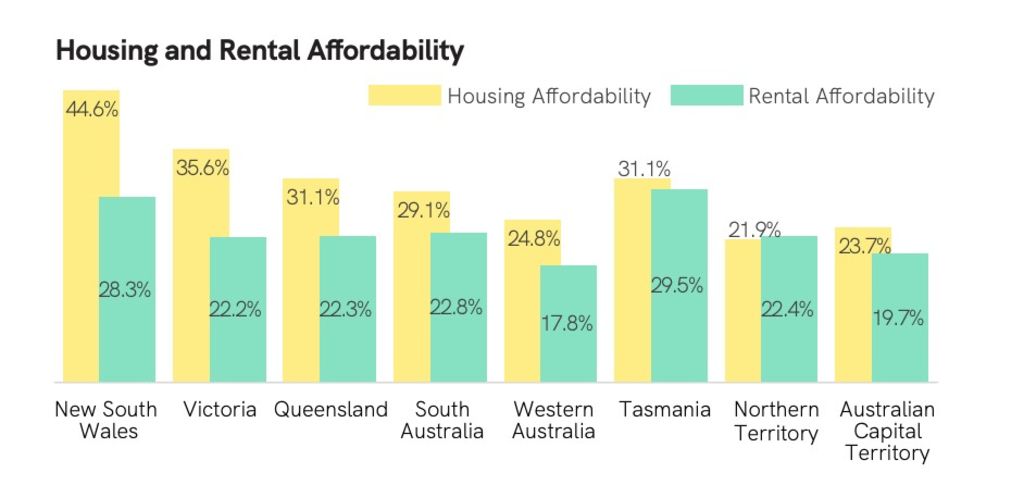

Although housing affordability was still better year-on-year (by 0.7 percentage points nationally), it worsened across New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory over 2020.

The housing market had defied predictions, said REIA president Adrian Kelly, with house prices rising across the country – largely driven by demand from first-home buyers, who increased their market share by 50.4 per cent over the year.

“Seeing this trend in conversion to home ownership is particularly great news given the challenges many tenants and investors faced over the pandemic, however surging house prices could see housing affordability obliterated unless measures to improve supply are implemented. This particularly applies to regional parts of Australia,” Mr Kelly said.

New South Wales saw the largest decline in affordability, with the proportion of income put towards repayments climbing 2.3 percentage points over the quarter to 44.6 per cent. It was followed by Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory with jumps of 2.2 and 1.6 percentage points.

Rental affordability also declined, Mr Kelly said, with the proportion of income put towards rent increasing to 24 per cent, up 0.4 percentage points over the year. Tasmania was the least affordable state, with tenants required to put 29.5 per cent of the average family income towards the median rent for a three-bedroom house.

Mr Kelly said housing affordability would only come under more pressure as investors returned to the market and immigration eventually picked up when borders reopened.

“We’re certainly not expecting affordability to improve and that’s simply because we don’t have enough homes to go around and sell and that’s because we haven’t been building enough homes for the last two decades,” he said.

The shift to regional areas from the big cities, accelerated by the coronavirus pandemic, had exacerbated affordability constraints in regional markets with tight housing supply – particularly in regional cities and centres along the east coast, he added.

“You’ve got long-term locals who have lived in these areas, who may have been paying $250 a week in rent and it’s now costing $400 and that’s happened virtually overnight.”

A national housing strategy was needed to ensure adequate housing supply, Mr Kelly said, as was a reduction in the cost and time involved in getting housing approved. The government also needed to look to rezoning reform, land release programs and an extension of the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme, among other measures, to support supply, he said.

Cuts to interest rates helped improve the affordability of mortgage repayments – and ultimately spurred on more buyer demand – but rates would need to go up a long way before they cooled the market, he added.

The Reserve Bank of Australia, which left the cash rate on hold at a record low of 0.1 per cent on Tuesday, was unlikely to use the rate to try curb rising prices, said Sarah Hunter, chief economist for BIS Oxford Economics.

Instead, it was likely to work with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) to rollout macro-prudential measures if needed, she said, but expected headwinds – such as the lagging apartment sector and lack of migration – to put a halt to rapid price growth before it got to that.

Dr Hunter said affordability had still been better year-on-year last quarter, despite price gains, as rate cuts did create a window of improved affordability for repayments before house prices responded to the change. Now that prices were rising, affordability was on the decline but still better than the previous peak.

“We’ve had four years of income growth and interest rate cuts … [but rising prices] will chew into that at some point, so if [the current growth] did keep going we’d see some intervention,” she said.

“Fundamentally, in the long term what impacts the price of property is supply and demand … if you want to permanently reduce the price … you need to shift that balance in favour of supply,” she added.

Professor Peter Phibbs, director of the Henry Halloran Trust at the University of Sydney, said supply should be increased – particularly the supply of social and affordable housing – but that it would not fix housing affordability, noting new supply in the capital cities was often limited to new apartments, or houses “in the middle of nowhere” that were already in limited demand.

New supply also takes time to deliver, so rate hikes or tighter macro-prudential measures would have more impact on property prices short term. The scheduled end of HomeBuilder, and cutting back other market incentives, would also help take the heat out of the market, he said.

“People are reacting the way they always do when rates go down, the price isn’t the sticker on their houses it’s the repayments that come out of their pay packet … because that amount has gone down people can get into the market who haven’t been in the market before, or they can upgrade,” he said.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More