Housing affordability is a problem. Here’s why super-for-housing isn’t a solution

The idea that young Australians should be able to dip into their super to help buy their first home keeps going round and round. The most recent iteration put forward by the Coalition’s Tim Wilson and a clutch of other backbenchers has the catchy slogan Home First, Super Second.

Wilson and co. are right in their diagnosis: Australia has a housing affordability problem. But they are wrong in their prescription: their proposal could actually make housing less affordable.

There are several much-better ways to revive the great Australian dream for young Australians.

Home ownership is plummeting

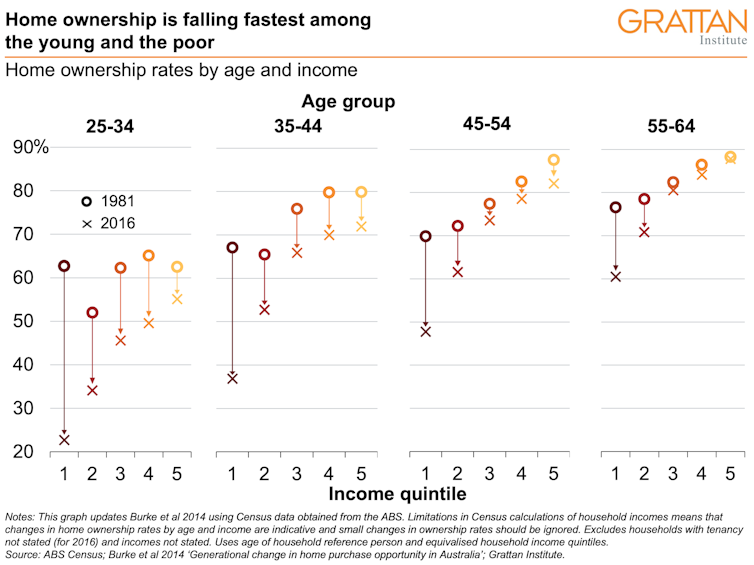

Home ownership rates are falling fast, especially among the young and poor.

In Australia today, fewer than half of 25-34 year-olds own their home.

Home ownership among the poorest fifth of that age group has fallen from 63% in 1981 to 23% today.

Today’s younger Australians are tomorrow’s retirees.

These trends suggest that by 2056 just two-thirds of retirees will own their homes, down from nearly 80 per cent today.

The government’s Retirement Income Review showed most homeowners on track for a comfortable retirement. But Australians who rent are facing an increasingly bleak future.

Senior Australians who rent in the private market are much more likely to suffer financial stress than homeowners or renters in public housing.

Nearly one half of all retired renters are in poverty — with incomes below half the median — when housing costs are taken into account. Their numbers will only grow as fewer retirees in future own their homes.

Super can’t much help

Saving for a deposit is the biggest hurdle to home ownership. In the early 1990s it took six years to save a 20 per cent deposit on an average home. Today it takes 10 years.

That’s why the Home First Super Second campaign is superficially attractive. It seems obvious that compulsory superannuation – forcing workers to save almost 10 per cent of their wages for retirement – stops many from buying a home, especially poorer younger Australians without access to the Bank of Mum and Dad.

And it’s true that allowing people to dip into their super to help buy a house would certainly not leave Australians impoverished in retirement.

Read more:

What matters is the home: most retirees well off, some very badly off

Grattan Institute research finds that most Australians would have a comfortable retirement even if they withdrew $20,000 early – because whatever they lost in super would largely be made up by a greater entitlement to the age pension.

But the problem for the Home First Super Second campaign is that allowing Australians to use their super to buy a home would do little if anything to increase home ownership rates.

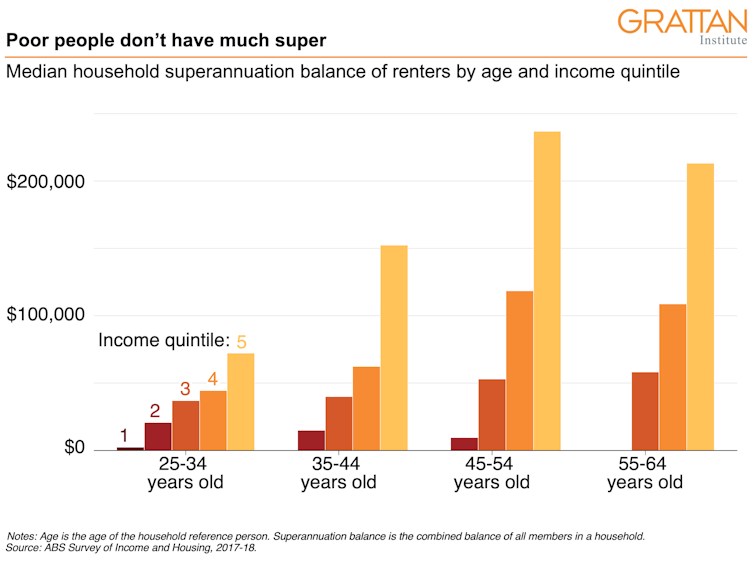

The younger, poorer Australians who are increasingly being priced out of home ownership don’t have much in the way of superannuation.

Read more:

Early access to super doesn’t justify higher compulsory contributions

The poorest 20 per cent of households headed by a 35-44 year old – precisely the group for whom home ownership is falling fast – typically have no superannuation.

The next poorest 20 per cent typically have only $15,000 in super.

It means allowing Australians to use their super for housing would mainly help wealthier people buy more expensive homes.

And there’s another problem: the more people you allow to use money from their super to buy a home, the more demand there is for housing.

Higher demand means higher prices, meaning the biggest winners would be the people who own homes already.

What can help is more homes

If Tim Wilson and the Morrison government really want to make housing affordable, they need to get more houses built.

Recent Grattan Institute research finds that relaxing planning rules to allow more homes to be built near the centres of Australia’s major cities would help.

Read more:

RBA research shows that zoning restrictions are driving up housing prices

The federal government has no direct control over planning rules, but it can provide incentives for state and local governments to relax planning rules, similar to those put forward by President Joe Biden in the United States.

As hard as it is, increasing the supply of housing — rather than pumping money from super into an already rising market — is the smartest way to make housing more affordable. Maybe Tim Wilson could start a campaign.![]()

Brendan Coates, Program Director, Household Finances, Grattan Institute and Will Mackey, Senior Associate, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More