How government intervention in the property market is actually harming it

Picture this: it’s a scene that plays out so often it seems inevitable. There’s an election campaign and a politician decides to shore up support by committing to a policy that’s proven to be popular: first-home buyer grants.

But what is the effect on the property market and the economy of these grants? No one knows definitively. Why?

The University of Sydney’s Cameron Murray said the way sales were reported made it nearly impossible to track and to research.

“The concerning thing in this is: why there is a gap [in knowledge]?” Dr Murray said. “Because property information, sales records and ownership records are difficult to get in this country.

“It’s almost an impossible task to match this up. So we have to go on secondary information and look at price changes in certain suburbs.”

While writing peer-reviewed research would help to discourage governments from undertaking the grants, which most agree didn’t work, governments seemed happy enough that they appeared to prevent prices from falling, he said.

So what do we know?

The approach by both state and federal governments to housing policy doesn’t work as a whole, and hasn’t achieved what it has set out to do since the post-war period, many housing experts and economists say.

Successive governments and successive policies haven’t made housing more widely available, and rapidly declining home ownership rates show this.

“It’s hard to think of any other policy that’s been pursued for so long in the face of such incontrovertible evidence that it doesn’t work.”

Housing is more unaffordable than it’s ever been, and academics and economists say the current economic consensus to housing, which tends towards as little government intervention as possible, must change if governments are to address any of their stated goals for housing policy.

Housing professor and author Hal Pawson said the idea that treating housing as a commodity and allowing market forces to dictate who got to own a home was misguided.

“[Governments] have put too much reliance on markets in the housing sphere,” the associate director of the City Futures Research Centre at UNSW said. “Housing doesn’t function in the same way as other commodities.

“It’s an experiment we’ve been living through for more than 25 years and it hasn’t had the effect that was hoped for.”

The experiment he refers to is demand-side stimulus in the form of grants for home buyers, mixed with tax settings which have turned housing into a wealth-creation vehicle for “mum and dad investors”. The grants exist in some form around the country, and have for decades.

Professor Pawson said the current era of housing policy began in 1996 when governments stepped away from regularly building public housing.

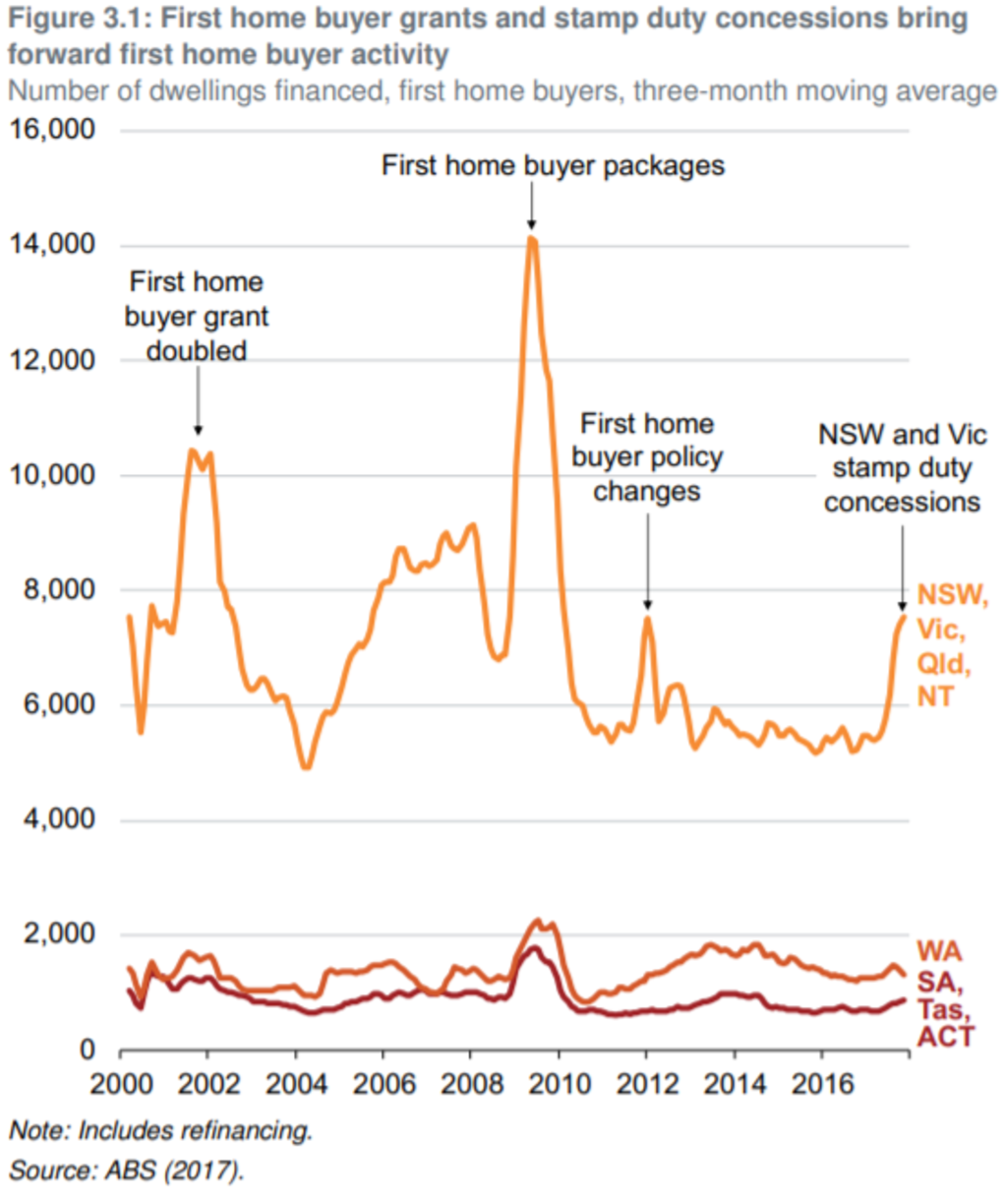

In 2000 the first grant-like scheme in this period began, offering buyers between $7000 to $14,000 to help them afford a property, in response to declining affordability.

Now, buyers can get as much as $20,000 to buy or build a new home in most states and territories, and some also offer stamp duty concessions.

The newest program in a similar vein to these grants was the HomeBuilder scheme. It offers $25,000 to people commencing a new build or renovation worth at least $150,000.

While they are effective at stimulating housing construction if targeted to new builds, they fail in almost every other measure.

“Housing is quite hard to turn the tap [supply] on enough very quickly,” Professor Pawson says.

The grants have done more to drive up housing demand than their stated aim of boosting housing supply, according to independent economist Saul Eslake.

“Up until the mid ’60s government policy was about boosting the supply of housing, not boosting the demand, but since then … governments lost enthusiasm for public housing,” Mr Eslake said.

“NIMBYism also emerged … so local and state government policy … switched to restricting supply rather than boosting it, whilst federal policy went to boosting demand [with first-home owner grants and changes to the capital gains tax grant, which boosted the appeal of negative gearing].”

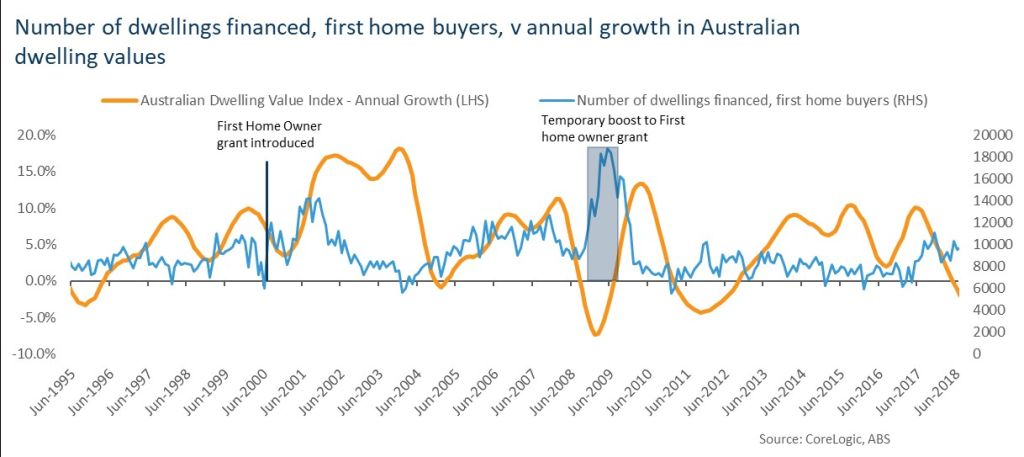

Mr Eslake said cash grants – particularly first-home grants, which date back to 1964 – typically brought forward activity that would have occurred anyway, drove up property prices and did more to help existing property owners and developers.

“It’s hard to think of any other policy that’s been pursued for so long in the face of such incontrovertible evidence that it doesn’t work,” Mr Eslake said.

CoreLogic head of research Eliza Owen said this was called the “vacuum effect”, and it often left prices higher once a spike was over.

“There was what appeared to be a vacuum effect around the early 2000s [and] the GFC, as government provided grants to boost first-home owner purchases and part of the reason that demand fell away after an initial spike was because property values started to rise,” she said.

Katrina Raynor, a postdoctoral research fellow in affordable housing at the University of Melbourne, agreed and said providing grants was generally a silly and inflationary policy.

“It depends on who you’re trying to help and who you’re trying to hinder, but if you’re trying to do anything about housing affordability they don’t work,” said Dr Raynor.

“What they tend to do, particularly in a buoyant market, is that if you give people an extra $10,000, the price of housing in the market goes up by $10,000 … you’re helping the existing home owners or developer.”

Another widely panned aspect of Australia’s housing policy are tax settings which enable the precarious private rental system.

Industry Super Australia chief economist Stephen Anthony said as they were, things like capital gains tax concessions and negative gearing were preventing the housing market from working as it should and created dangerous levels of personal debt in the community.

“The tax policies let mum and dad buy one property after the other as a way of creating a retirement portfolio,” he said. “We had a debt frenzy and now the Australian household is the most indebted in the world. It’s the financial anchor that will sink us all.”

While in good times the debt load wasn’t too much of a big deal, it was a drag on the economy in the bad times, Mr Anthony said.

Housing policy could be improved by using tax settings as a supply-side stimulus, rather than using government cash to prop-up demand, he said.

Mr Anothony said tax breaks for institutions to create build-to-rent buildings was one way to increase supply, but should be paired with discouraging mum and dad investors from creating unneeded demand in buying houses by cutting negative gearing and other concessions.

Professor Pawson said while this was not the only solution, it would rein in price increases and make the whole system more sustainable.

“If a bigger component of our housing system was institutional interests, we’d have a system that’s not fickle and liable to respond by falling off a cliff, or being consumed by a house price boom when the dial turns in the other direction,” he said.

Professor Pawson said this could also be supported by a greater construction of social housing, which advocacy groups and academics had been pressuring the government to build for years.

But failing that, experts tend to agree a national housing strategy that names a problem and attempts to resolve it across Australia would also work better than piecemeal demand-side stimulus across the states and territories.

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More