How much would Australia's house prices have risen without COVID-19?

Australia’s property prices have risen well above what they would have if COVID-19 had never happened, new analysis shows.

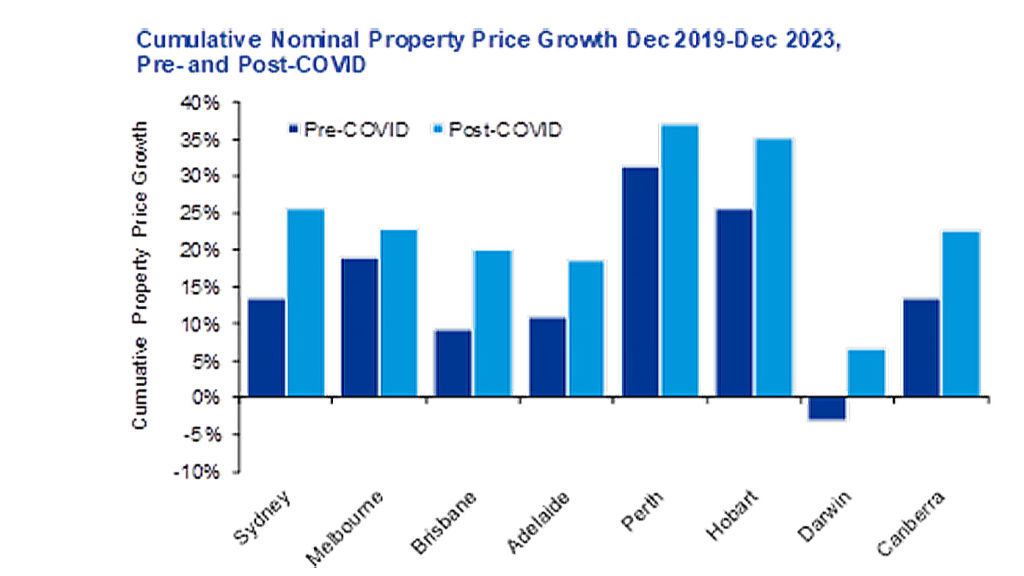

Most capital cities were due for an upswing in 2020, according to a report from KPMG Economics, but ultra-low interest rates and government support to the housing market during the pandemic gave the market a further shot in the arm, adding hundreds of thousands of dollars extra to property values.

The report The Impact of COVID on Australia’s Residential Property Market assessed what had taken place over the past 18 months compared to a no-COVID-19 scenario and found that nationwide, house prices were now between 4 to 12 per cent higher and units up to 13 per cent higher than they would have been if the world had stayed “normal”.

In a “normal” 2020 scenario, pandemic policy responses, such as pushing the cash rate down to 0.1 per cent and introducing the HomeBuilder program, would not have happened.

Under KPMG’s modelling, without the pandemic, house prices in Sydney would have risen 13 per cent to hit $1,119,000 by December 2023. Now they’ll rise 26 per cent to $1,244,000.

Brisbane’s house prices would have risen a modest 9 per cent to $601,000; instead, they’ll rise a massive 20 per cent to $661,000.

| Capital | Median house price Dec 19 | Median house price Dec 23 without Covid |

Median house price with Covid 2023

|

| Sydney | $986,000 | $1,119,000 | $1,244,000 |

| Melbourne | $760,000 | $905,000 | $940,000 |

| Brisbane | $550,000 | $601,000 | $661,000 |

| Adelaide | $485,000 | $537,000 | $576,000 |

| Perth | $495,000 | $650,000 | $667,000 |

| Hobart | $519,000 | $651,000 | $701,000 |

| Darwin | $470,000 | $455,000 | $501,000 |

| Canberra | $745,000 | $846,000 | $913,000 |

Melbourne would have risen 19 per cent to $905,000; instead, they’ll rise 24 per cent to $940,000. Darwin — the only capital where houses prices were modelled to fall — will instead see prices rise by $31,000.

Brendan Rynne, KPMG chief economist, said the initial uncertainty caused by the pandemic and consequent economic downturn saw a 3 per cent fall in prices in the June 2020 quarter. But it didn’t last long.

“Once market participants became confident that the pandemic would not result in a free-fall of home values, a combination of monetary and fiscal policies quickly began to push things the other way,” Dr Rynne said.

“The material decline in mortgage interest rates; extra savings from not spending on holidays and leisure; and generous income support from government and housing market support specifically, has seen property prices rise dramatically in the past six to nine months, past the point where they would have risen under a no-COVID scenario.

“It appears these short-term positive factors have swamped the longer term-negative factors associated with the housing market, such as lower population due to the fall in migration.”

But the paper said that soaring price growth would temper over the next two years as mortgage rates rise and the fundamentals of the housing market begin to “reassert themselves”.

Dr Rynne said the longer-term negative factors like rising mortgage rates and lower population growth — Australia’s population is now anticipated to be lower by about 1 million people by the end of this decade compared with pre-pandemic forecasts — would moderate the pace of the price rises.

“Supply, too, plays a role. Our analysis of dwelling approvals in the big cities shows that in Melbourne and Sydney, there are 25,000 and 20,000 respectively fewer houses and units available than would have been the case in a no-COVID scenario,” he said.

Dr Rynne said the Covid price premium widened the housing wealth gap between the “haves” and the “have-nots”.

“There’s one group where it particularly matters, and that’s people who don’t already own a home,” he said.

“In terms of negative outcomes, it has distribution effect where those who own get richer, and those that don’t own get left behind even more.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More