'It’s certainly out of the box': The Iranian project that gets experimental with eco-friendly design

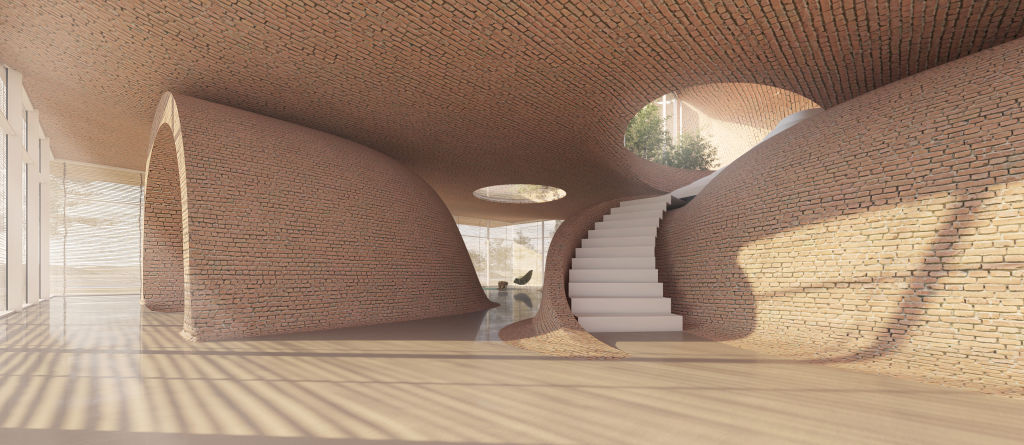

It appears to be made from improbable shapes, architecture too sophisticated to be true. Yet this futuristic home in Iran is a feat of engineering as much as it is impressive design.

The Guyim Vault House is one of the eight global projects shortlisted for the “house – future project” category of the World Architecture Festival. The festival, judged by an international panel in Amsterdam next month, rewards architecture that addresses today’s ecological and societal challenges, such as an ageing population, climate change and water waste.

Nextoffice, the architects behind the Guyim Vault House, say the main challenge was the cross-arched domes – a complex structure often seen in Iranian architecture.

They have arranged the floor slabs to create dome-like volumes with flexible borders between indoor and outdoor areas. The result is a series of half-domes on the ground floor that create closed and semi-closed spaces, their arched backs facing each other and a glass cube enveloping them. The ground floor also houses a living room, changing room, mudroom and kitchen.

On the first floor there are three half-domes facing each other to create a sunken central courtyard. Bedrooms are connected to this area.

Quadruple arc structures, or domes on four arches, as seen in the Guyim Vault House are called “chartaqi” in Persian. These structures trace back to the Sasanian Empire, the last kingdom of the Persian Empire before the rise of Islam.

Domes were commonly built in mausoleums and palaces in Sasanid times, between 224 and 651 AD, because they were thought to bring people closer to the powers of heaven.

Domes are still prevalent in Iranian architecture today with intricately tiled structures adorning the country’s mosques, most famously the Imam Mosque at Naghsh-e Jahan Square in the central Iranian city of Isfahan.

- Related: Rent these pod homes on Airbnb

- Related: Bahamas island lists for $118m

- Related: Icelandic retreat in lava fields opens

The Guyim Vault House may look like a spaceship version of these traditional domes, but that’s all part of its appeal. Some are placed inside the cube, while some protrude like mounds of sand, leaving the border between the interior and the exterior on both levels undefined.

Dr Sam Bowker, lecturer in art history and visual culture at Charles Sturt University, says this futuristic take on traditional architecture is reminiscent of the famous Farnsworth House in Illinois, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

“From first impressions, it seems to be finding experimental and vernacular answers to well-established modernist conventions,” he says.

“The exposed chartaqi curvature is like a very loose or open muqarnas structure, especially as a device to support elevated layers, yet they are encased in a pavilion-like glass structure.”

Van der Rohe designed Farnsworth House between 1945 and 1951. However, according to Bowker, he’s not the only master architect to inspire the design.

“It’s like an organic structure has been excavated from a remote archaeological site and raised above the ground,” he says.

“In some ways these partial domes also remind me of the brick Tabun ovens familiar to villages across the Middle East, but stylised with the glossy futuristic ambition that characterised the work of Zaha Hadid,” he says.

Iraqi-born UK architect Hadid, who passed away in 2016, was known as “the queen of the curve” for the fluid shapes and forms of her buildings.

Whatever the project’s past, present and future influences, it’s certainly one out of the box, says Bowker.

“We’re seeing a proposal for an experimental design that tries to feel of its place, but also wants to make a global statement.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More