'Tsunami' of older Australians at risk of homelessness: AHURI report

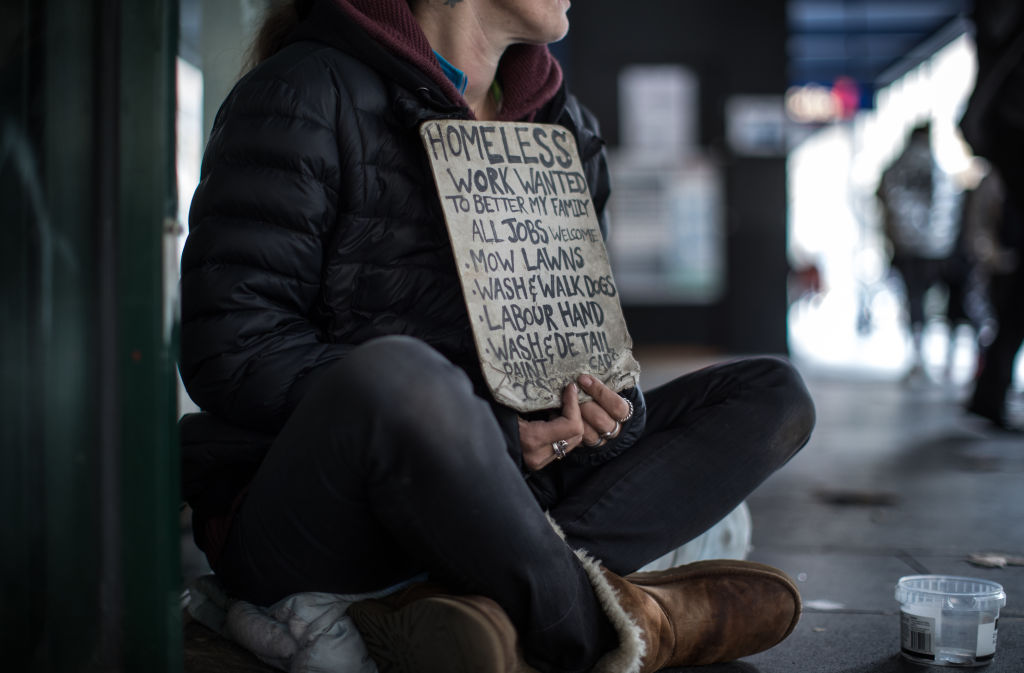

Older Australians are increasingly at risk of homelessness, with life shocks in senior years leaving many without a roof over their head for the first time, new research shows.

Health problems, relationship breakdowns, deaths in the family and rental evictions are among the key factors leaving lifelong renters and property owners homeless in later years, according to an Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI) report.

The proportion of homeless people aged 65 to 74 years old jumped almost 40 per cent in the five years to 2016, and one in every seven people homeless at the last Census was over 55.

“I don’t think people realise how quickly that problem has grown and how much further it has to grow,” said report co-author Professor Andrew Beer of the University of South Australia.

With more Baby Boomers reaching retirement and those in Generation X more likely to rent for life, Professor Beer said, Australia was at “the very start of a tsunami of older persons becoming homeless”.

“That’s a major concern because unless we get the structural issues right to fix the problem, we’re going to see elderly people dying in the streets.”

Domestic and family violence, housing crises and financial difficulties were the three main reasons older Australians sought specialist homelessness services in 2017-18, according to the report by researchers from the University of South Australia and Swinburne University of Technology.

Indigenous people over 65 were 12.3 times more likely to access services than their non-indigenous counterparts.

Those with “conventional housing histories” who experience a financial or other shock late in life are one of three broad groups of older Australians that become homeless.

People with a history of transient work or unstable housing and those who previously experienced homelessness, are the others.

Support for these groups is fragmented, poorly resourced and unable to provide long-term solutions, the report found. Of 1518 homelessness services across the country, only three are specialist services for older people.

“When homelessness is experienced for the first time later in life, people commonly have limited knowledge of welfare and homelessness services,” the report said. “In addition, as often happens, if they do not see themselves as someone who is homeless, they are less likely to access traditional homelessness services.”

Those older clients that do seek help are spending longer in those services, which the researchers say suggests they are having difficulty finding appropriate housing options.

With about a third of people over 55 living on less than $400 a week, boosting the supply of affordable, secure and appropriate housing was key, Professor Beer said.

“[The government] simply has to build the housing that needs to be provided,” he said. “Older homeless Australians can never get a job again; a market-based solution simply isn’t going to work for them,” he added, noting supplying housing would cut costs for other government services.

Making welfare support – particularly online systems – easier to use for older Australians was also key, with the report noting: “Centrelink has become more difficult to navigate over the past two decades”.

In one incident, recounted at a workshop for the homeless and those in the sector, an older migrant was deterred from seeking help when they were shouted at and told to sit down while standing close to Centrelink reception to make sure they could hear when called.

Other priorities include funding to enable aged-care providers to build specialist facilities for older clients, and reviewing, increasing and indexing the Homelessness Supplement for aged-care providers, the report said.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More