Man converts muddy abandoned cottage into $300,000 first home

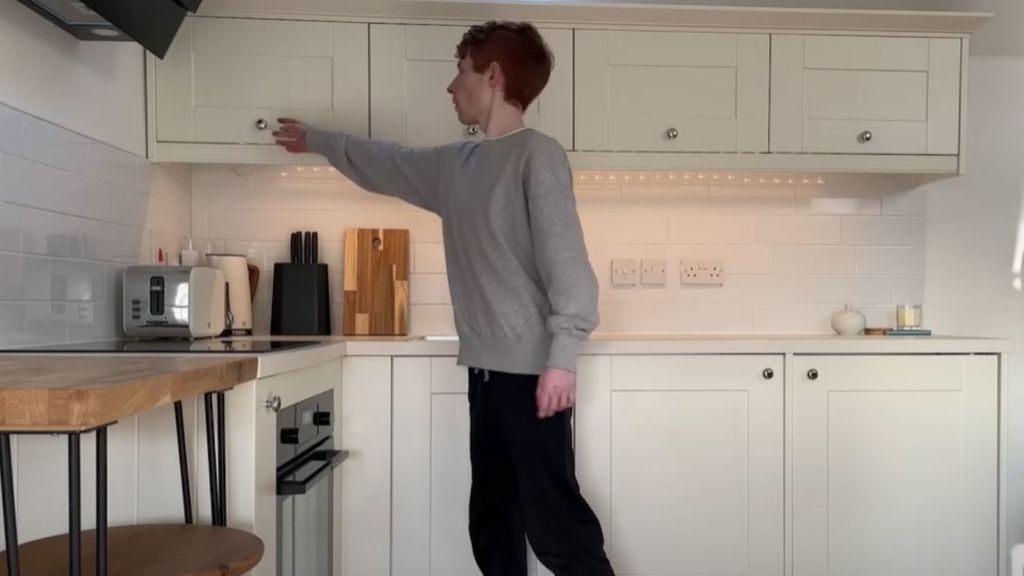

A young man has shown what is possible in property, buying a muddy and abandoned stone cottage and turning it into a $300,000 custom first home.

The Scottish homeowner braved torrid conditions to bring his dream to life over 12 months, and shares every step with millions of fans on his You Tube channel.

George Dunnett has almost 250,000 subscribers watching him turn the once derelict Kinnesswood cottage – which is down the road from where he grew up in the town, an hour from Edinburgh – into a comfortable and stylish house.

His his popular video, I Bought An Abandoned Tiny House, has been viewed 17 million times.

He paid £102,458 (about $AU196,820) in reno costs atop the £55,386 ($AU106,352) to buy the house, and generously shares the full spreadsheet of outgoings with his followers in a video titled How Much Did My Tiny House Cost? The reno took less than a year, using a joiner, an electrician and a blacksmith to craft the stair railing, among others.

“In my village there is a little lane called The Cobbles, which I walk up everyday, and on The Cobbles there are three abandoned or empty buildings, First of all, there is this tiny building – I don’ts know who owns it and I don’t know what’s inside, so honestly, it is a bit of mystery,” Dunnett says in the video.

The second is empty but is used as the village museum.

“Finally, we have this building which was pretty much abandoned. It was being used for storage and it was looking very old and very tired, and no-one had lived it for way over 50 years and every time I walked past it I thought it would be nice to turn it into a proper house, so in October 2020, I bought it.”

Dunnett explains that the walls “were looking pretty rough”, the floor was ground and mud and there was damp. “In short, there was a lot of foundational work needing to be done before I was at the stage of picking out my curtains,” he says.

One of the biggest challenges was connecting the water and sewerage, which included the cost of closing the road.

He said a real estate agent valued the property at £155,00 (about $AU297,300), and that was two years ago.

Dunnett says it was a “good deal”, given he has a house in which he has chosen “every little aspect”.

This year he listed the cottage for rent on Airbnb and has moved onto his next project.

The time it takes to save for a first home in Australia has sped up, but it’s still almost half a decade of sacrifice.

Young Aussies need just shy of five years to save for a house deposit, but not if you want to buy in Sydney, 2024 data shows.

The cash rate has given and taken away for first-home buyers – savings accounts are accruing more interest, helping hit a deposit sooner, but mortgages have become more expensive, according to Domain figures.

The Domain First-Home Buyer Report 2024 (released in February) shows the average, double-income young Aussie couple will need four years and nine months to scrounge a 20 per cent deposit for a typical entry-level priced house. That is two months shorter than a year ago.

Sydneysiders need longer – six years and eight months. The New South Wales capital has the lengthiest saving time for debutant buyers.

However, Domain’s chief of economics and research Dr Nicola Powell said the slightly faster time it takes to get a 20 per cent deposit – which avoids lenders’ mortgage insurance – comes with caveats.

One of those is the hard yakka it takes to service a mortgage, with rates at the highest level since November 2011.

However, the hiking cash rate has helped first-home buyers quicken the time it takes to gather a deposit by providing improved interest on savings deposits.

“Mortgage affordability has really blown out, so it takes a larger proportion of your income to make those repayments,” Dr Powell says. “The other flip side is a higher cash rate means you get greater interest accrued on savings, so savings rates are better, and – the research looks at compounding interest over time – that rate has helped anyone about to squirrel away some extra cash.”

Regional buyers have a fighting chance, where entry-priced units require 23.6 per cent of income and entry houses 30.8 per cent.

For buyers in metro areas, the financial pinch is tighter – for the combined capital cities, entry houses demand 46.5 per cent of income and entry units 30.7 per cent.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More