Murray measured the indoor temperature at home. The results were shocking

Keeping warm in winter consumes Murray Mayes’ life. Their public housing unit regularly drops below 18 degrees, to temperatures considered unhealthy by the World Health Organisation.

Summer is also a struggle as Mayes’ chronic health condition flares in cold and hot temperatures, leaving them bedridden. Heating and cooling the thermally inefficient unit is expensive.

“If I’m not running the heater constantly, it takes about five minutes for the temperature to normalise to whatever the temperature outside is,” they said. “Particularly with the price rises with power that’s become bloody difficult to deal with.”

Mayes took part in tenants’ advocacy group Better Renting’s study of rental temperatures as a “renter researcher”, in which 59 tenants tracked how cold it was inside between June and August. At the coldest, Murray’s home in Sydney’s inner west got to 11.3 degrees.

Of the renters studied, 85 per cent had a median temperature below 18 degrees in their homes over winter and 46 per cent had median temperatures of below 16 degrees.

The results were worse in NSW (94 per cent below a median of 18 degrees) and Victoria (90 per cent). WA recorded 83 per cent, and in Queensland where no tenants studied had a median temperature below this threshold, the homes were too cold 18 per cent of the time.

Mayes is on the disability support pension and often tries to get through the worst temperatures without heating.

And it’s worse in summer, when Mayes is housebound. “I can barely keep my eyes open, chronic fatigue, I’ll be throwing up, barely able to move my limbs with the pain I’ve been in.”

Better Renting executive director Joel Dignam said renters were living in poorly insulated homes, without efficient heaters and other temperature efficiency-improving features like double-glazed windows or draught stoppers.

The rental crisis was exacerbating the issue, he said.

“It does mean we have people stuck in these particularly bad properties. Another thing that’s gotten worse over the past year is the inability to do anything about it,” Dignam said.

“From renters we’re hearing: ‘there’s nowhere else we can go … Even though living here sucks, it’s better than not having somewhere to live’.

“There’s also a sense of futility. What’s the point of asking and risking retaliation if it might not even get fixed anyway?”

Other renters who took part in the study said their homes’ frigid temperatures cost them hundreds in bills, exacerbated health issues and made them feel socially isolated, given they felt their home was too uncomfortable to socialise in.

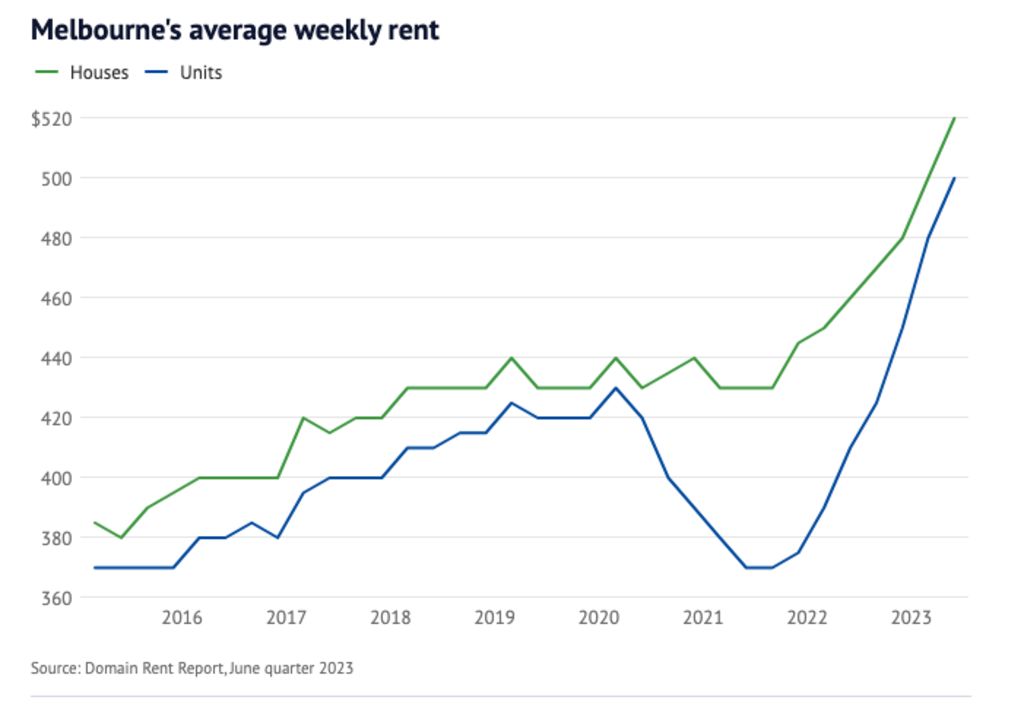

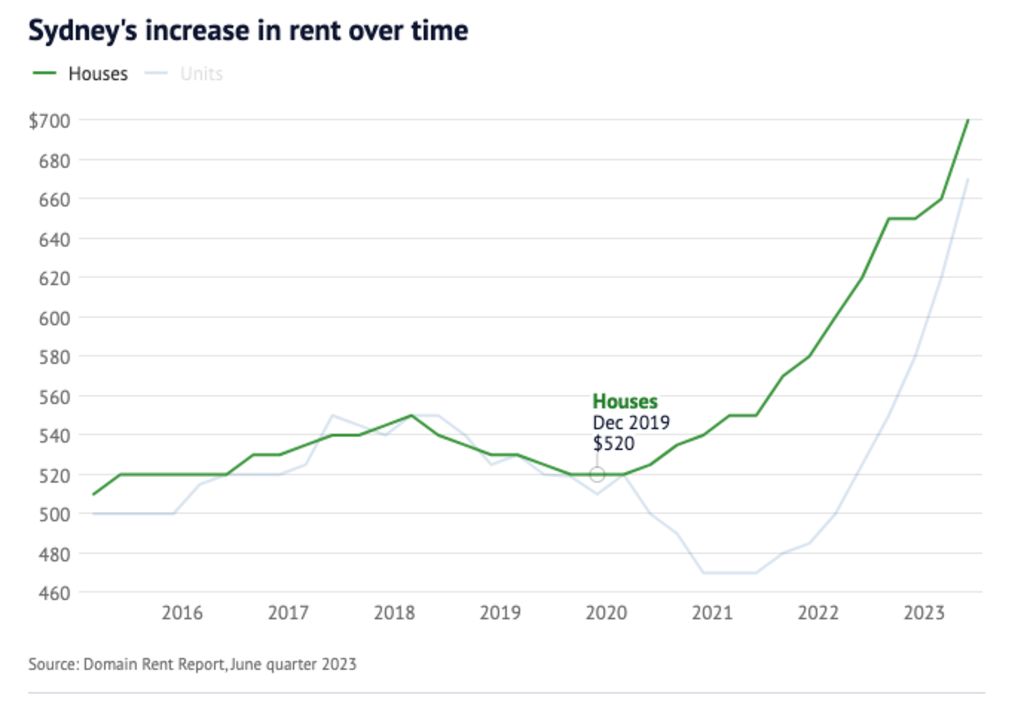

It comes as the rental vacancy rate holds at low levels, 1 per cent in both Sydney and Melbourne in August, on Domain data. It was 0.8 per cent in Brisbane and 0.3 per cent in Perth. A balanced market is about 3 per cent.

Amid competition for homes, unit rents jumped 27.6 per cent in Sydney over the year to June, 22 per cent in Melbourne, 17.8 per cent in Brisbane and 20 per cent in Perth.

University of NSW’s City Futures Research Centre senior research fellow Chris Martin, who was not involved in the project, said although the study was limited it illustrated the issue of poor energy efficiency in rentals.

He agreed the rental crisis would lead to tenants accepting substandard living conditions.

“When vacancy rates are as low as they are, those high rents that we’re seeing advertised are calling new supply into the market that just wouldn’t have been rented a few years ago,” he said. “Shabby, run-down stuff that people just shouldn’t live in.”

Real Estate Institute of Australia deputy president Leanne Pilkington said thermal efficiency in rentals was an issue.

“It would be challenging, if you were living in a home that was always cold,” she said.

Pilkington said tenants could improve their chances of getting temperature regulating improvements if they maintained a good relationship with their property manager and did their homework before moving in.

“You’ve got to have a look at the property closely,” she said.

“But I understand it’s not that easy to get rentals so it can be challenging.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More