Not easy being green: Australia is still building four in every five new houses to no more than the minimum energy standard

New housing in Australia must meet minimum energy performance requirements. We wondered how many buildings exceeded the minimum standard. What our analysis found is that four in five new houses are being built to the minimum standard and a negligible proportion to an optimal performance standard.

Before these standards were introduced the average performance of housing was found to be around 1.5 stars. The current minimum across most of Australia is six stars under the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS).

This six-star minimum falls short of what is optimal in terms of environmental, economic and social outcomes. It’s also below the minimum set by many other countries.

There have been calls for these minimum standards to be raised. However, many policymakers and building industry stakeholders believe the market will lift performance beyond minimum standards and so there is no need to raise these.

What did the data show?

We wanted to understand what was happening in the market to see if consumers or regulation were driving the energy performance of new housing. To do this we explored the NatHERS data set of building approvals for new Class 1 housing (detached and row houses) in Australia from May 2016 (when all data sets were integrated by CSIRO and Sustainability Victoria) to December 2018.

Our analysis focuses on new housing in Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania and the ACT, all of which apply the minimum six-star NatHERS requirement. The other states have local variations to the standard, while New South Wales uses the BASIX index to determine the environmental impact of housing.

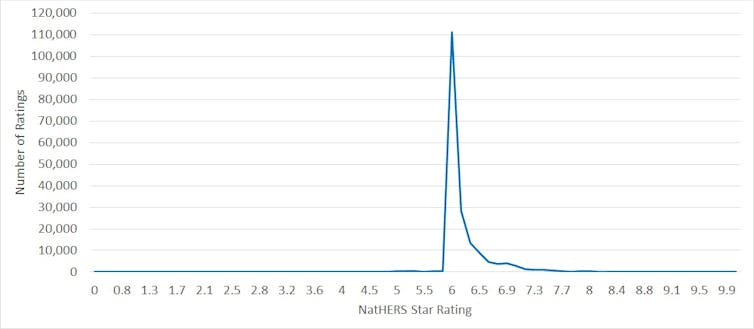

The chart below shows the performance for 187,320 house ratings. Almost 82 per cent just met the minimum standard (6.0-6.4 star). Another 16 per cent performed just above the minimum standard (6.5-6.9 star).

Only 1.5 per cent were designed to perform at the economically optimal 7.5 stars and beyond. By this we mean a balance between the extra upfront building costs and the savings and benefits from lifetime building performance.

Author provided

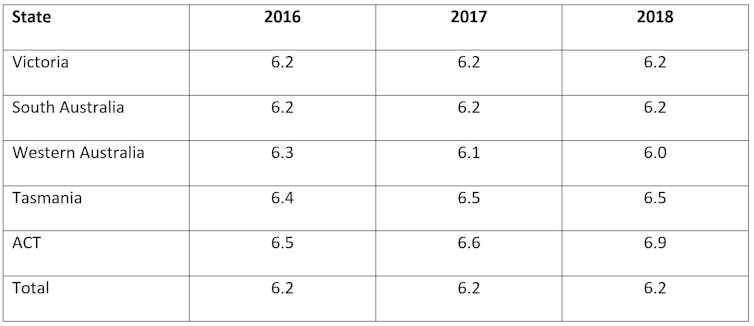

The average rating is 6.2 stars across the states. This has not changed since 2016.

Author provided

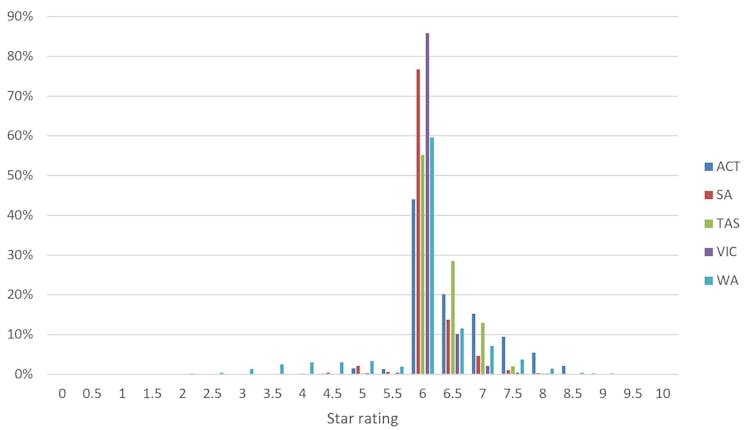

The data analysis shows that, while most housing is built to the minimum standard, the cooler temperate regions (Tasmania, ACT) have more houses above 7.0 stars compared with the warm temperate states.

Author provided

The ACT increased average performance each year from 6.5 stars in 2016 to 6.9 stars in 2018. This was not seen in any other state or territory.

The ACT is the only region with mandatory disclosure of the energy rating on sale or lease of property. The market can thus value the relative energy efficiency of buildings. Providing this otherwise invisible information may have empowered consumers to demand slightly better performance.

We are paying for accepting a lower standard

The evidence suggests consumers are not acting rationally or making decisions to maximise their financial wellbeing. Rather, they just accept the minimum performance the building sector delivers.

Higher energy efficiency or even environmental sustainability in housing provides not only significant benefits to the individual but also to society. And these improvements can be delivered for little additional cost.

The fact that these improvements aren’t being made suggests there are significant barriers to the market operating efficiently. This is despite increasing awareness among consumers and in the housing industry about the rising cost of energy.

Eight years after the introduction of the six-star NatHERS minimum requirement for new housing in Australia, the results show the market is delivering four out of five houses that just meet this requirement. With only 1.5 per cent designed to 7.5 stars or beyond, regulation rather than the economically optimal energy rating is clearly driving the energy performance of Australian homes.

Increasing the minimum performance standard is the most effective way to improve the energy outcomes.

The next opportunity for increasing the minimum energy requirement will be 2022. Australian housing standards were already about 2.0 NatHERS stars behind comparable developed countries in 2008. If mandatory energy ratings aren’t increased, Australia will fall further behind international best practice.

If we continue to create a legacy of homes with relatively poor energy performance, making the transition to a low-energy and low-carbon economy is likely to get progressively more challenging and expensive.

Recent research has calculated that a delay in increasing minimum performance requirements from 2019 to 2022 will result in an estimated $1.1 billion (to 2050) in avoidable household energy bills. That’s an extra 3 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions.

Our research confirms the policy proposition that minimum house energy regulations based on the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme are a powerful instrument for delivering better environmental and energy outcomes. While introducing minimum standards has significantly lifted the bottom end of the market, those standards should be reviewed regularly to ensure optimal economic and environmental outcomes.

Trivess Moore, Lecturer, RMIT University; Michael Ambrose, Research Team Leader, CSIRO, and Stephen Berry, Research fellow, University of South Australia

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More