Pandemic savings put brakes on household debt risk: economists

The war chest of savings Australians have built during the pandemic, coupled with less than breakneck annual growth in housing prices, is reducing the risks of our high household debt load, economists say.

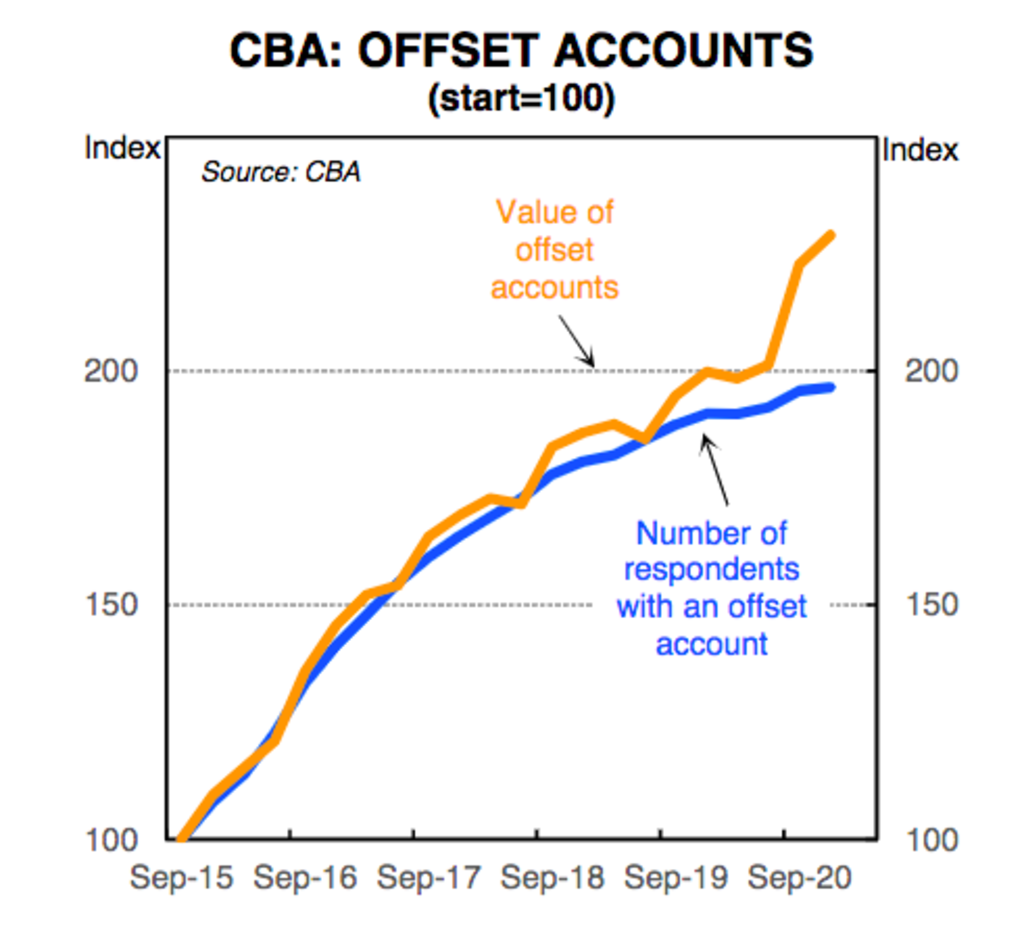

As the economy continues to recover from the pandemic and more workers regain employment, new analysis shows borrowers are boosting their offset accounts as well as returning to paying down their mortgages.

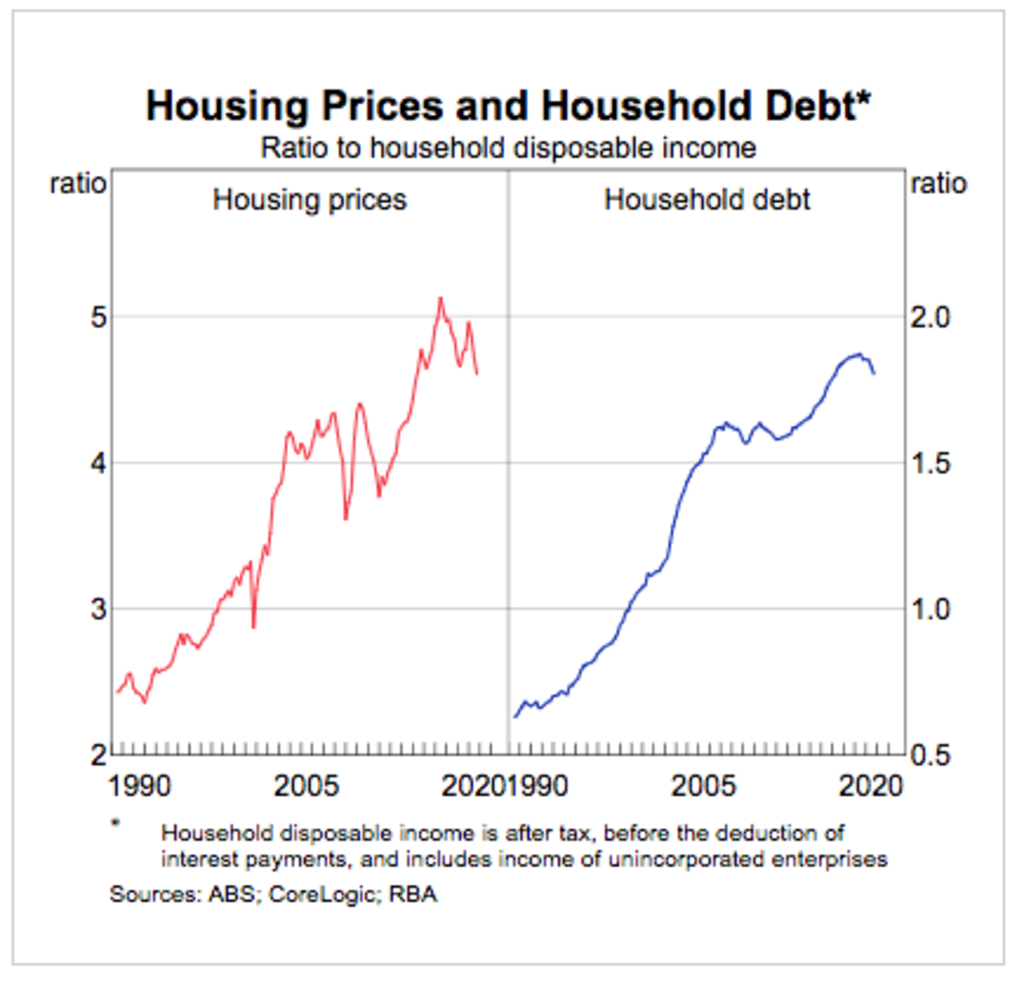

The high level of household debt in Australia has worried experts for years, approaching 200 per cent of household income in recent years, before edging slightly lower, but not before prompting warnings it could pose a risk in any crisis.

But the stimulus deployed to get Australia through the pandemic, including low interest rates, wage subsidies and mortgage holidays, has helped to lower the risk of the debt load, economists say.

Households squirrelled away almost $119 billion into their savings accounts last year, figures released by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, revealed.

At the end of October, the big four banks held a record $813.3 billion in savings from households, up $78.8 billion over the previous 12 months, with almost all the growth occurring since the pandemic.

CBA senior economist Kristina Clifton said its latest analysis showed the value of CBA offset accounts had increased much faster than the number of accounts held at the bank over recent months and that the government’s stimulus payments had allowed households to accrue a large stock of savings.

“The reason we’ve seen that lift in savings, basically comes down to the fact that the government stimulus payments through covid have been so large with the JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments, as well as a number of different one-off cash payments to households,” she said.

“On top of that we saw a big contraction in household spending in the second quarter of last year when the coronavirus restrictions and lockdowns were in place across the country.”

She said these factors, coupled with ongoing cuts to interest rates, had allowed households to not just accumulate savings but also to service their debt, which was reducing the risk posed by overall household debt load.

Westpac chief economist Bill Evans agrees that households’ increasing ability to repay their debts during the pandemic has slowed the growth of household debt over the past year.

“What’s happening at the moment, while people are still cautious about spending and as their incomes have been rising with these various stimulus boosts, is that your lending might have been increasing, but your repayments have also been exploding, so household debt hasn’t been growing,” he said.

“So, while the strength of the market is showing up in the new lending, repayments are also growing more rapidly than normal, containing the growth in household debt.”

However, Mr Evans said it would only be a matter of time before “the authorities get nervous” about household debt again as house prices rise.

Home values in every capital city rose in December, according to CoreLogic, while the September quarter Domain House Price Report found house prices rose in every capital city except Melbourne, which was flat.

The Reserve Bank has also noted a permanent one percentage point reduction in official interest rates can push house prices up 30 per cent in three years.

“I expect 2023, will be the year that the authorities will move themselves into the picture again and I expect the macro-prudential weapon will be out on the table then,” Mr Evans said.

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver also believes macro-prudential controls, such as caps on interest-only lending and limiting banks’ investor loan growth, could be re-introduced in “a year or two” to help slow housing prices and credit growth and stabilise the risk posed by our high household debt, but not any sooner.

With households stockpiling billions of dollars in savings during the pandemic, and interest rates remaining low for the foreseeable future, not even the winding up of subsidies such as JobKeeper and JobSeeker or the end of mortgage holidays was likely to cause any immediate concern, he said.

“The most recent job numbers show the unemployment rate has come down a lot faster than expected and the number of people actually needing JobKeeper now I think has probably collapsed,” he said.

“Likewise, the proportion of loans by value still impacted by payment holidays has also collapsed, from about 11 per cent of total mortgages in May, down to 2.8 per cent in October. So, it is quite low and so the removal of various supports is unlikely to cause any major problems with debt levels.”

But he warns the real issue will come later.

“We had record housing finance numbers. At some point that’s going cause a rebound in the debt growth and then I think the Reserve Bank will start to get more concerned and that could well take us down the path of more macro-prudential controls again,” he said.

New loan commitments for housing rose 5.6 per cent to $24 billion in the month to November, official figures showed, a record high.

“Those kind of macro-prudential interventions could still be a year or two away because at the moment I think the RBA would say, ‘well, if we look at average house prices, across Australia, they’re only just getting back to where they were in 2017′,” he said.

“Debt levels have not gone up much really over the last few years, because while some people have been taking out new loans, a lot of other Australians have been using JobKeeper to pay down their loans, so at this stage the Reserve Bank wouldn’t be too concerned.”

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More

- © 2025, CoStar Group Inc.