Planting greenery on roofs can help improve air quality inside buildings: study

Covering the roofs of apartment and office buildings with plants can help improve the quality of air inside and lift property values, according to a growing body of green infrastructure research.

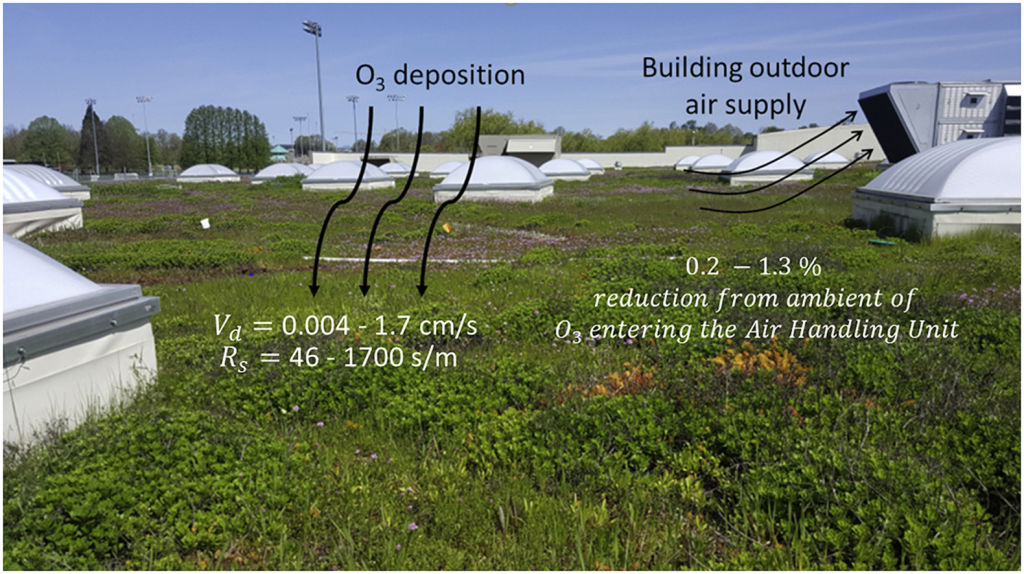

Most recently, an article published by US researchers in the Building and Environment journal showed growing greenery on the roof of a building and near the air intakes could help to reduce the levels of ozone, one of the gases which makes up smog and is harmful to breathe.

The pilot study on the impact of green roofs on ozone levels near building ventilation air supply showed a green roof could reduce the ambient ozone level by up to 1.3 per cent.

A green roof can be a roof surface totally covered with vegetation, or rooftop facilities which include planted trees and other greenery.

Encouraging the uptake of green infrastructure needs to be a high priority for all levels of Australian governments, Associate Professor Sara Wilkinson, of the University of Technology Sydney, said.

“I think it’s vital to continue to keep our cities liveable,” she said.

Associate Professor Wilkinson was previously involved in a study which showed adding green infrastructure could lift residential property values from 6 per cent to 15 per cent.

Another benefit was reducing the urban heat-island effect, a phenomenon where urban areas hold more heat due to high concentrations of concrete and a lack of vegetation, she said.

“More than 500 people died in [the 2014 heatwave]. Those numbers will increase if we don’t do something.”

“Living infrastructure” company Junglefy founder Jock Gammon said he entered the field to meet a need he saw for green walls, roofs and facades.

“We thought our cities were heading in the wrong direction in the way they were being built,” he said. “There’s a real disconnect with how our cities are and how we are as humans.

“[We have] an innate connection with nature. It makes us less stressed and we feel more secure around it.”

Mr Gammon has helped to fund research in the past and is an advocate for 202020 Vision, a campaign to make urban areas 20 per cent greener by 2020.

He says making the benefits of green infrastructure more well known would help promote its voluntary uptake.

“We’ve funded research with UTS for four years, and it’s a big part of what we’re about,” he said. “Providing metrics that engineers and developers can use can help make informed decisions.”

Green walls and roofs have been springing up in apartment buildings over recent years, as developers tap into a human desire to feel connected to nature in a bid to make their project stand out.

Frasers Property installed green walls at its residential and retail complex Central Park in Sydney’s Chippendale and at its mixed-use Discovery Point project in Wolli Creek. In Melbourne, the developer is adding a rooftop urban farm above the retail component of Burwood Brickworks.

Another prominent Melbourne apartment block to add vertical gardens is the Platinum Tower on Southbank’s City Road, by Salvo Property Group, while a nearby twin-tower project planned by Beulah International is set to feature greenery on its facade when complete.

A totally voluntary uptake policy within local governments wasn’t the best solution though, Associate Professor Wilikinson said. Singapore has seen some of the highest construction levels of green infrastructure in the world through voluntary policies, but in name only.

“Because they have a big proportion of [state-owned buildings] and it was a state policy, ergo all those buildings were given green infrastructure and the uptake was high,” she said. “In Singapore, voluntary is more mandatory.”

The high cost and safety risks of maintaining green infrastructure was also a barrier to their uptake, but Associate Professor Wilkinson said she was working on solutions to minimise these issues such as watering and maintenance robots.

She added the price premiums attracted by apartment buildings with green infrastructure were also often enough to warrant their inclusion by developers.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More