Rift along generational lines emerges among architects considering profession's activism

An attitudinal rift has emerged at the nation’s largest annual architecture conferences between older, more established practitioners and the younger, rising generation, over the role of the profession in activism.

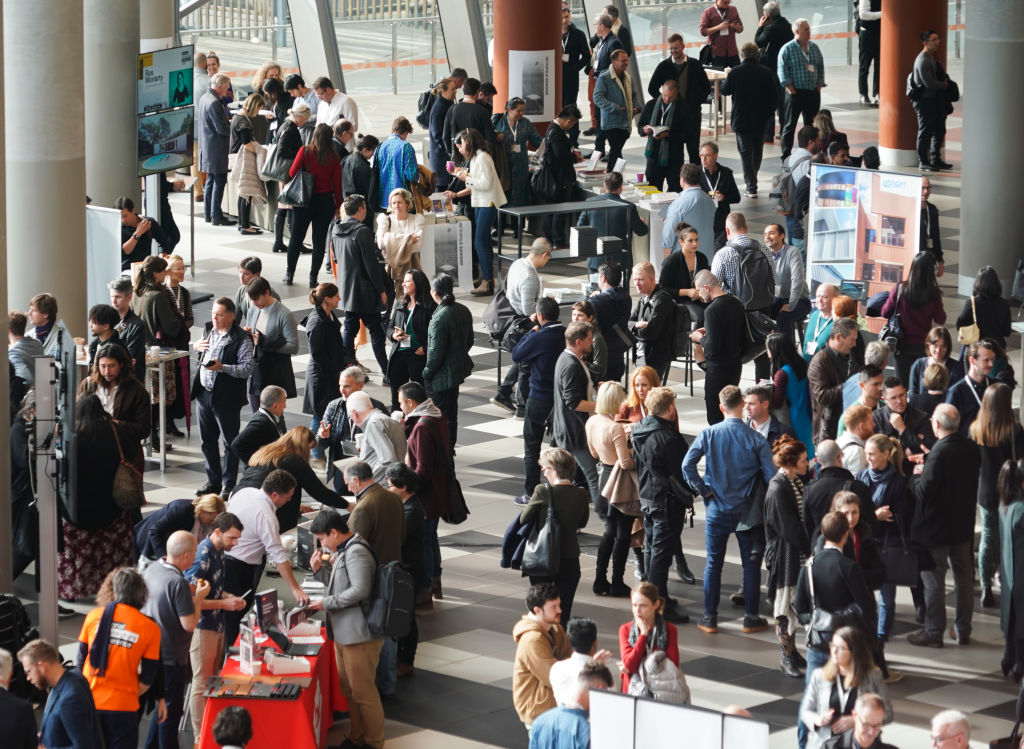

At the weekend’s 2019 National Architecture Conference, 1000 architects from around the country came together in Melbourne to listen to leading practitioners — many from overseas — address the overarching and overtly political theme of “Collective Agency”, that explored modes of advocacy and activism that can be bought into play in the fast-changing business of making the built environment.

Jeremy McLeod is one of the local heroes redefining the role of the architect. Through the Nightingale 1 project in Melbourne, he has demonstrated there can be more than profit involved in making housing that is attractive to the market.

He offered his summary of the new paradigm being put before the gathering.

Essentially, he said, it’s now a matter “of ethics over aesthetics”.

Through most of the eight long and intense sessions, attendees heard how it is their duty to take more responsibility for how they are using land and resources. All sorts of new protocols are needed, and it is the architect’s job to insist on them.

A notably high proportion of presentations dealt with the need to acknowledge traditional owners in more than token ways in any developments in Australia because “100 per cent of it takes place on Indigenous country”.

As Tasmanian Aboriginal descendant and architect with JCB, Sarah Lynn Reese put it: “Country is not just land, country is everything: land, water, animals, plants and us. Everything we consume comes from country.”

The reiteration of so many calls for collective activism had some of the older practitioners grumbling that it was all “too academic and self-indulgent”. Where were the more usual presentations on individual buildings that might inspire their own work?

“That’s what collective agency is all about,” said one student. “So, of course, there’s some splash back.”

Though there were many shades of receptivity through the different age strata, it was the younger groups that generally endorsed the approach of conference curators Stephen Choi and Monique Woodward that the job of an educative forum was “about making people uncomfortable”.

Other issues discussed were affordable housing and the potential of multiple generations more commonly sharing digs; the need to elevate and enshrine much better benchmarks of design quality, and the pending arrival of the sci-fi style smart cities that will be wired with so many sensors they’ll be capable of managing “the metabolism” of a city so that a significant degree of chaos and congestion might be ironed out in situations of “fully regulated computational urbanism”.

“Smart urbanism, spreadsheet urbanism, the smart city” will, according to Australian-trained, New York-based multi-platform architect Farzin Lotfi-Jam, disrupt and change architecture “at an incredible pace”. He’s optimistic; however, it will open up “more space for imagination and engagement”.

As a long-schooled profession whose work has such a long-term impact on public and private realms, architects are acutely aware that their job carries a heavy social freight and they don’t duck the responsibility.

But the curators this year confessed that they had set out to be super provocative.

Choi, from the Living Futures Institute, admitted “we are deliberately talking about political and environmental issues to calcified power structures in our society. We are here to challenge the status quo” — “to get things done takes courage and bravery,” added Monique Woodward.

In the session entitled “Advocacy and Influence”, New Zealand Maori architect Elisapeta Hata said there “needed to be a shift in the conversation, because if we don’t change the dialogue now, we’re just going to leave it to the next generation to untangle”.

“And it will take more than building another McMansion and shoving a bunch of solar panels on it.”

The concluding speaker, Australian Institute of Architects past president Shelley Penn, said it was about tiny acts (as individual practitioners). “But we must also work as a collective of architects, and as humans in the world as well.”

“We have to be the ones to step up, in whatever way we can,” she said. We are trained to be more responsible than just competent. We are trained to do the real work. The work that is hard to do.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More