Rise in home airconditioning contributes to global warming, protects from heat stress

A rise in the use of airconditioners as the weather heats up is prompting a vicious circle by contributing to global warming, but has the side effect of also protecting against heat-related illnesses, a new report found.

And, experts warn the poor design of much of Australia’s housing stock is making the problem worse, as residents rely on airconditioning to keep cool instead of shading or cross-ventilation.

It comes as the nation braces for summer after the hottest November on record, with bushfires already burning on Queensland’s Fraser Island and warnings of flood risk.

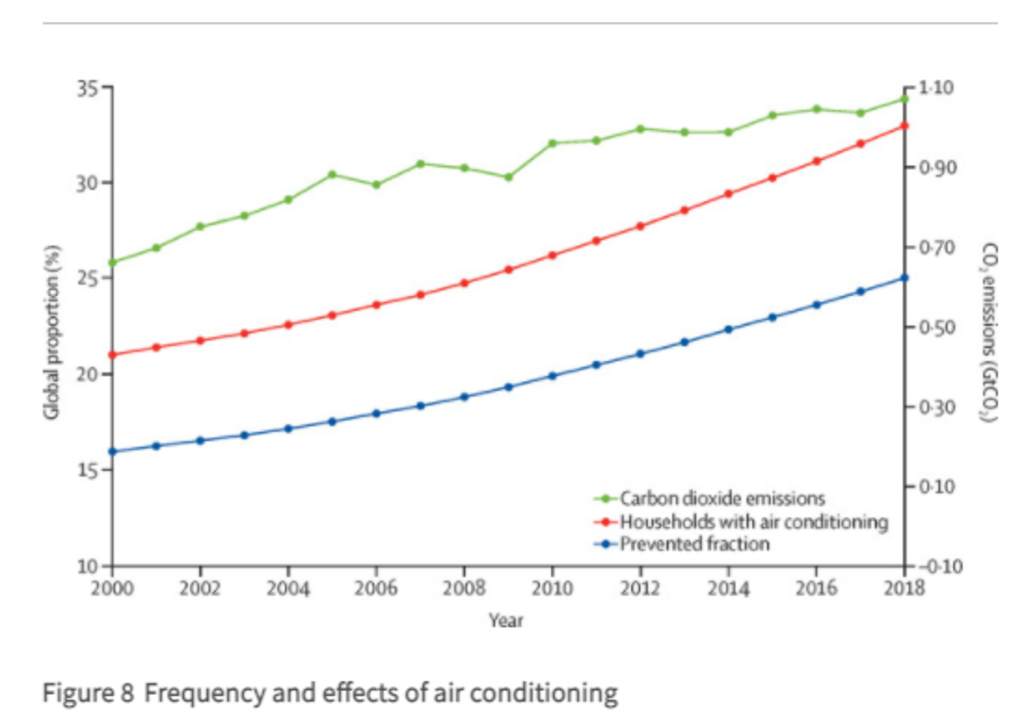

The world’s airconditioning stock has been rising and reached 8.5 per cent of global electricity consumption in 2018, according to the 2020 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change, published last week.

This contributes to climate change, air pollution, and peak electricity demand, and emits waste heat that adds to the urban heat island effect, the report said.

It cited research finding increased use of airconditioning as the climate warms could result in about 1000 extra air pollution-linked deaths every summer just in the eastern US by 2050.

By contrast, airconditioning was found to protect against heat-related illnesses.

Of the total possible deaths from heatwaves, the proportion prevented by airconditioning rose from 23.6 per cent in 2016 to 25 per cent in 2018, according to the report.

Global frequency of airconditioning, and effect on climate change and health

Local experts said airconditioning use is on the rise in Australia, prompted by the poor quality of many homes that are not designed to keep occupants cool in summer.

“It’s definitely true that more and more people are getting airconditioning,” said lecturer and researcher in the school of property, construction and project management at RMIT University Nicola Willand. “It’s also definitely true that if you are too hot in your home – especially if you are very young, if you’ve got a chronic illness, if you’re aged – then you’re vulnerable to heat stress.

“It comes back to housing quality. If the housing is bad, the housing itself can’t protect you from heat passively. You need airconditioning to keep cool.”

Dr Willand warned of energy poverty among older people, who may be worried about the cost of running airconditioning and not understand that reverse cycle airconditioners are very efficient, especially for cooling.

Alternatives such as visiting an airconditioned shopping centre may not work for those without the means, or groups that are at higher risk from COVID-19 and avoiding crowds this summer.

Better solutions include cross-ventilation, opening windows on the cool side of the house, using blinds and external shading to block the sun and turning on a ceiling fan while at home.

She highlighted the Victorian government’s post-covid stimulus plans for retrofits of lower-income households and newly built energy efficient public housing.

“Energy services like heating in winter and cooling in summer are essential for quality of life and health,” Dr Willand said.

“So many developing countries are now pushing to improve housing as part of the covid rebuild because it’s good for the environment, it’s good for health, it’s good for everyone.”

Airconditioning must not be the only way to stay cool as heatwaves can coincide with network outages, warned QUT associate professor in Energy Science Wendy Miller.

Australia does not have good quality buildings that protect occupants well from heat when the power goes out, she warned, describing a building that needs air conditioning to stay habitable as like a “leaky boat” that needs to pump out water and keep it afloat.

“We have the slip, slop, slap and slide [saying] for ourselves,” she said. “But we don’t apply that same approach to our houses.

“Now would be a really good time for government to invest in improving the quality of our building stock, starting with the poorest quality housing, rental housing et cetera to improve the comfort of those houses so people don’t have to rely on airconditioning.

“That will boost jobs as well as providing better housing and better social equity.”

UTS associate professor in the School of Architecture Leena Thomas said a rise in larger houses that don’t allow for easy cross-ventilation was partly behind the rise in home airconditioning.

“Once you have the airconditioning in, most people will tend to use it for a lot of the time,” she said. “And, for many days when you could do much more to manage the way in which your house is coping in heat.

“A lot of homes now are in tighter urban lots which have less greenery. The urban heat island effect is often greater, as a consequence of that.”

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More