Robin Boyd was an architect of the ages and is still relevant today

Anyone with a passing knowledge of Australia’s architectural history will be aware of the resonance of Robin Boyd’s name.

Forty years after his death, and 56 years after publication of his instant classic, the strident critique of Australia’s built environment, The Australian Ugliness, the Victorian architect and polymath remains a towering presence because what he was talking passionately about then is almost as relevant today.

Here is his voice in The Age in 1948 as he discourses on Melbourne’s untrammelled growth: “New shapeless suburbs sprawl heartily on the surrounding country. They grow without grace, without charm, far beyond the recall of the metropolitan transport system, beyond the last call of the milkman, beyond the gas, the sewerage, the shops, the theatres, the hotels …”

To give a more accurate measure of this creative genius, critic, theorist and stirrer, and a man Tony Lee described as “Australia’s design evangelist”, the executive director of the Robin Boyd Foundation, whose charter is to keep alive “the spirit” of Boyd’s work, provides a remarkable scale reference.

In 1947, during the height of the postwar housing shortage, The Age, in collaboration with the Victorian chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects commenced an accessible design bureau, the Small Homes Service.

Then in his late 20s, Boyd was its first director and authored many of the weekly treatises published in the then broadsheet.

Championing the relatively novel ideas of Modernism; of open plan layouts, big windows, solar and site-responsive orientation, low-profile rooves and indoor/outdoor connectedness, the Service provided £5 architect-designed plans to owner-builders – or intending new home owners, who would engage a builder to construct their affordable family house.

The impact of the Service was, says Lee, unprecedented and has never been replicated – anywhere.

“For the last few generations, architects have struggled to affect [design] even 5 per cent of new housing.

“Through 1948-9, from Robin’s reports, 20 per cent of houses built in Melbourne were using Small Homes Service plans.

“So, never anywhere in the world have architects had so much influence on rendered housing. The reach was phenomenal.”

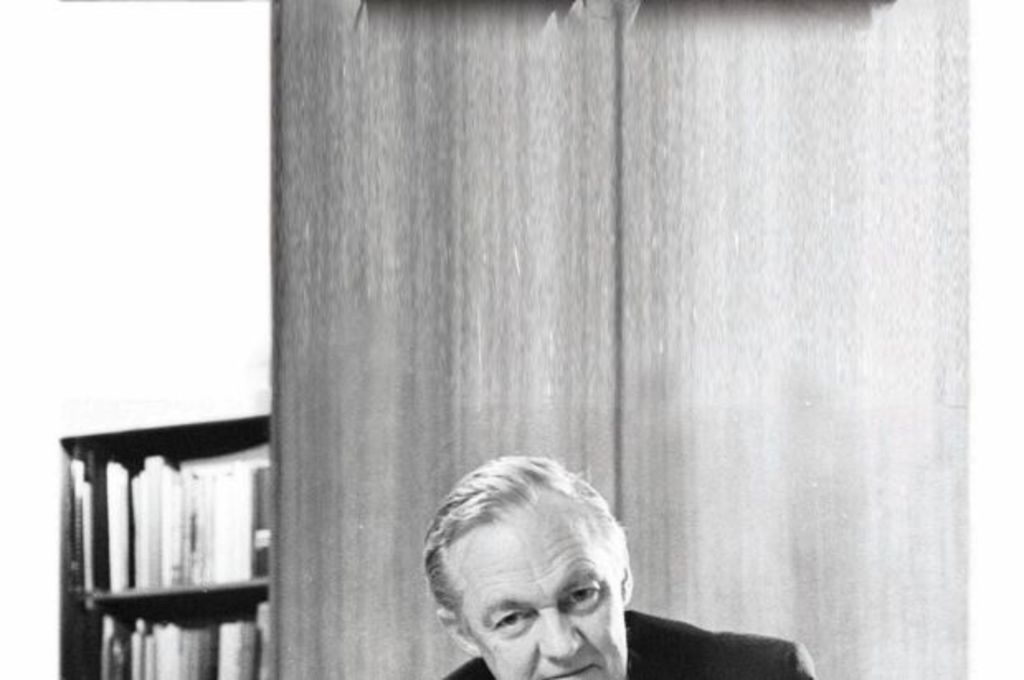

Why? “I suspect”, says Lee, sitting at his desk that was previously Robin Boyd’s own cork-surfaced desk in Boyd’s last family home in Walsh Street, South Yarra, now the foundation’s headquarters, “it was because Robin chose to write a two-tiered article that firstly showed the housing [in plan and drawing], and then explained the rationale for it.

“In educating the public about the benefits of good design, he was also developing an audience.”

As well as Boyd’s innate literary propulsion, his writing found such a wide readership because “it was so eloquent and unpretentious”.

“After the war when The Age only ran six to seven news pages, almost a full page was given to the Small Homes Service,” Lee says. “And after it was published on a Wednesday or Thursday it became dinner party conversation across Melbourne for a week.”

Readers wanting to get hold of plan could write in or drop by The Age bureau in the city and pick up one of what eventually became thousands of different design options.

The two-storey, dual-pavilion 1958 Walsh Street house that has a courtyard at its heart is, to architect Lee’s mind, “one of his best houses … the last one he designed for himself”. It was occupied by Boyd’s widow Patricia until 2005 when the foundation bought it for use as a venue for its myriad endeavours.

Next week, on May 15, it will serve as the backdrop for a classical guitar concert to be given by one of Boyd’s grandchildren, Rupert Boyd.

Looking about, Lee explains that the house “epitomises Robin because, like most architect’s own homes, it is his architectural autobiography”.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More