Sydney housing 'overvalued' as Australian home buyers take on more debt compared to incomes: UBS

Sydney property prices are overvalued and Australian households are taking on more debt compared to their incomes to keep up, a new report from investment bank UBS has warned.

But there’s little relief in sight for homebuyers as property prices are likely to keep rising unless interest rates go up, the report said, a scenario the Reserve Bank views as unlikely before 2024.

It comes as AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver estimated Sydney house prices were as much as 39 per cent overvalued, on one measure, and units about 30 per cent, and forecast prices would keep rising next year but at a slower pace. The city had been overvalued since the early 2000s but the degree of overvaluation had varied, he said.

Elsewhere, NAB slightly revised up its dwelling price growth forecasts to 23 per cent during 2021 and a further 5 per cent in 2022 across the capital cities, from its previous expectations of 19 per cent this year and 4 per cent next year. It tipped growth for Sydney of 27.5 per cent, Melbourne of 18.8 per cent, Hobart of 28.4 per cent, Brisbane of 23.2 per cent and Perth of 14.5 per cent.

The property market has boomed over the past year as pandemic-era buyers armed with record-low interest rates, government stimuli and cash saved from cancelled overseas holidays chased larger accommodation while spending more time at home.

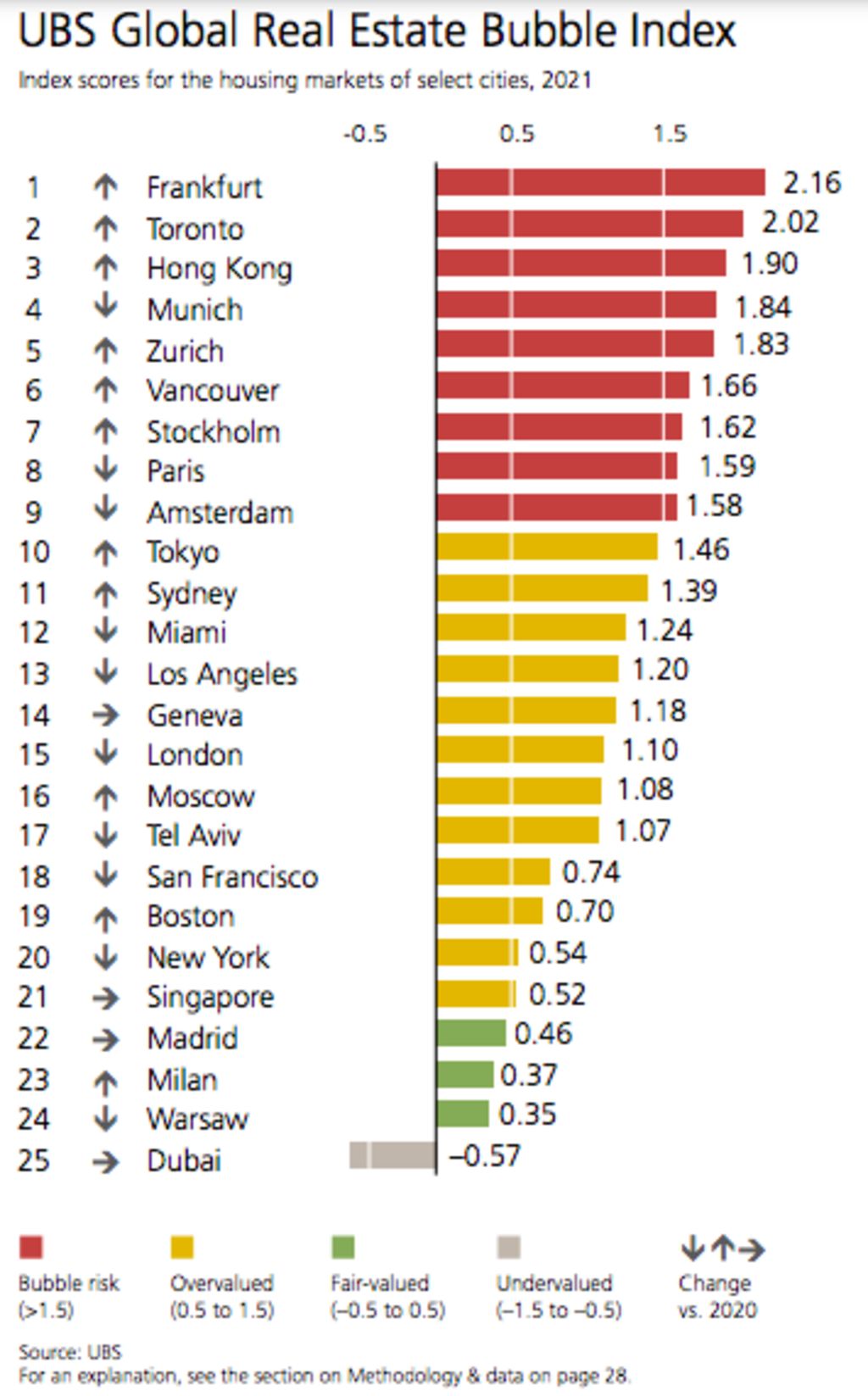

In its Global Real Estate Bubble Index for 2021, UBS found Sydney was more overvalued than London or New York, but it stopped short of calling the city’s housing market a bubble. Frankfurt, Toronto and Hong Kong topped the rankings of the cities with the most bubble risk.

Any city that scores over 1.5 points on the index is deemed at bubble risk. Sydney is at 1.39 and has risen to 11th place in the rankings.

“Households have to borrow increasingly large amounts of money to keep up with higher prices,” UBS warned. “As a result, the growth of outstanding mortgages has accelerated almost everywhere in the last quarters, and debt-to-income ratios have risen—most markedly in Canada, Hong Kong, and Australia.”

Banks and governments face pressure to act, and lending standards are being tightened, which could stop price growth in most global cities, the report said. Debt-to-income ratios have been in focus, with Treasurer Josh Frydenberg recently backing a possible clampdown on large loans relative to incomes.

As for Sydney, a previous dip in the market was brief, property prices have posted new record highs, and they are likely to keep rising without an interest-rate hike, UBS said.

“Price growth has clearly outpaced local incomes, stretching affordability and thereby increasing dependance on easy financing conditions even further,” the bank said.

“Monetary policy is likely to stay accommodative for the time being. A tightening of lending rules would likely result in a setback for prices.”

To afford a 60-square-metre apartment near the centre of Sydney, the average skilled service worker would need to work for eight years, compared to five years in 2011, the report found.

For an investor, a flat of the same size would need to be rented out for 30 years to pay for the flat, up from 20 years in 2011.

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver said when house prices were compared to rents and adjusted for the low-inflation environment, Sydney house prices were about 39 per cent above fair value, and Melbourne somewhat similar. This measure compares rent prices to owner-occupied properties, however, for which buyers might be willing to spend more.

“The fact that housing is poorly affordable is a sign of overvaluation, but it hasn’t stopped housing in Sydney or elsewhere in Australia getting more expensive,” he said. “I wouldn’t be saying, just because it’s overvalued it’s about to fall.”

But Mr Oliver said he did not expect prices to continue to rise at the same boom-time pace, and expected a modest price rise of 7 per cent during 2022 as it became harder to get a large home loan.

BIS Oxford Economics chief economist Sarah Hunter said she also expected momentum in the property market to moderate.

“It’s definitely become a lot more unaffordable over the last 15 months,” she said. “In July, August last year when the market started to turn, a key group driving that was first-home buyers – they’re now falling back.”

A pick-up in wages growth or other sources of household income would improve affordability, she said.

The bank regulator’s decision this month to reduce the maximum amount someone could borrow to buy property by about 5 per cent would have a dampening effect on momentum, she added.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More