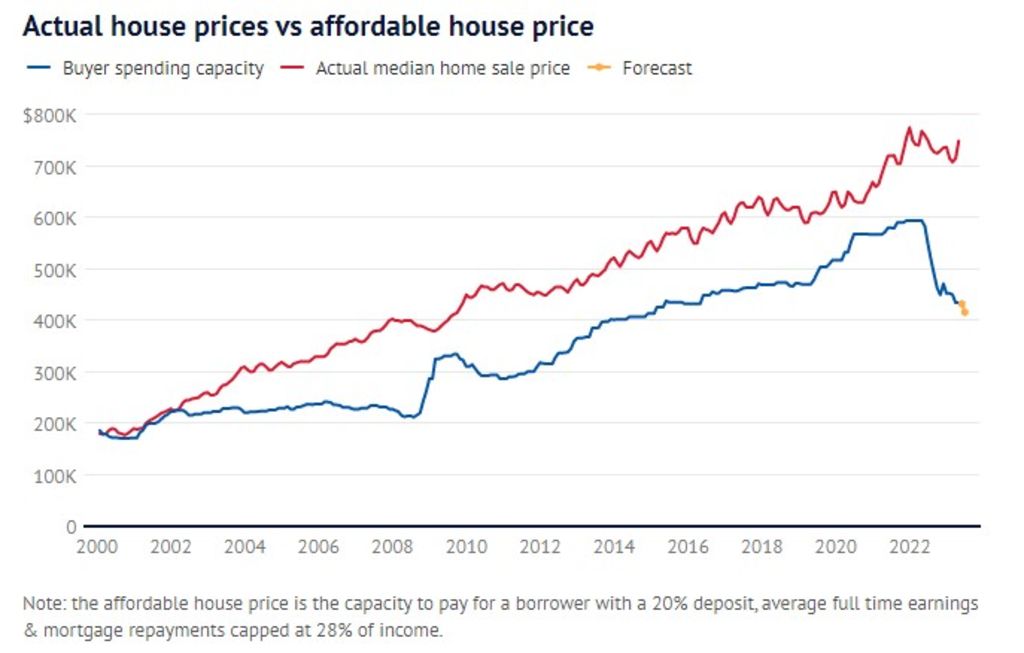

The graph that shows why being thrifty is not enough for home buyers

Soaring interest rates have pushed down home buyer budgets much faster than property prices have fallen, leaving average income earners further behind.

The gap between the cost of a typical home and the amount an average Australian can borrow has more than doubled since cash rate hikes began a year ago, and is likely to worsen as interest rates climb to an 11-year-high.

Borrowing capacity will be further cut following the Reserve Bank’s decision on Tuesday to lift the cash rate another 25 basis points to 3.85 per cent. The latest hike comes at a time when strong buyer demand and low supply has been putting upward pressure on property prices.

While that imbalance between supply and demand has prompted a chorus of economists to revise up their house price outlooks, any potential growth will still be constrained by buyer budgets.

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver said spending power for the average income earner as of April was down 26.9 per cent from the peak, and could reach a 30 per cent drop if the cash rate lifted another 50 basis points over May and June.

Oliver said many economists, including himself, previously expected capital city home values to fall 15 to 20 per cent off the back of the sharp decline in spending power.

“Obviously though it hasn’t panned out that way, we’ve seen a 9 to 10 per cent fall, and prices have flicked back up again due to a shortage of property and a surge in immigration,” he said.

That sharper drop in spending power had exacerbated the growing gap between median prices and what the average Australian can afford – which was virtually non-existent in the year 2000.

The median home sale price nationally in April was $749,000, about 72 per cent above what a buyer on average full-time earnings could afford at $434,650, modelling shows. That is up from about a 29 per cent gap the previous April, when the cash rate was at a record low of 0.1 per cent.

Oliver said increased reliance on the Bank of Mum and Dad could be a factor in the mismatch between spending power and prices, alongside buyers not borrowing to their full capacity to begin with, and the lagged effect of rate hikes.

However, he expects the recent uptick in prices to be constrained by affordability limitations, and for values to end the year flat or slightly up, before lifting 5 per cent next year off the back of rate cuts. Further downside risk remains given poor affordability, the potential for further rate hikes and the slowing economy.

“Either interest rates have to come down or property prices have to come down … [the gap] can’t continue to grow, sooner or later something will give,” Oliver said.

Barrenjoey chief economist Jo Masters said the ability of buyers to drive prices higher was constrained by reduced borrowing power, and sustained increases in prices were unlikely until a drop in the cash rate – which she expects next year.

“It’s hard to imagine prices being driven up much when what I can borrow is 30 per cent less,” she said, adding buyers were being forced to save longer for a deposit or opt for a cheaper property.

Masters in March revised her peak-to-trough decline from 16 per cent to 12 per cent, and tipped prices to fall 5.7 per cent this year.

She attributed recent price growth to stronger than expected migration, and a shortage of homes for sale – with listing levels at about a third of the ten-year average.

Gains were also largely being led by the more affluent upper end of the market, she said.

Commonwealth Bank chief economist Gareth Aird said new entrants to the housing market could not buy the same quality of dwelling that they had been able to in the past.

“Affordability has gotten worse … someone on the average income now can’t buy as good a dwelling as 20 years ago,” he said.

“[But there’s also been] a structural change in the number of people working, most [households now] have a dual income,” he added, noting this had also contributed to the gap between prices and the average income.

Aird revised his forecasts this week, predicting prices to rise 3 per cent this year and 5 per cent next, off the back of surging population growth, low supply, and a highly competitive rental market.

Sydney mortgage broker Anthony Landahl, managing director at Equilibria Finance, said clients had seen their borrowing power drop about 30 per cent, leaving them unable to afford properties they could have a year ago, despite the downturn.

“Some people are stepping back and focusing on saving more of a deposit. Some are looking at recalibrating where they may be able to afford a property,” he said.

Others were turning to the Bank of Mum and Dad, he said, but the key challenge had shifted from saving a deposit to being able to afford a mortgage, especially as the cost of living rises.

We recommend

RBA lifts the cash rate to 4.35 per cent to curb inflation

Dexus takes heart from rate cut

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More