The most extravagant unfinished mansion in Los Angeles

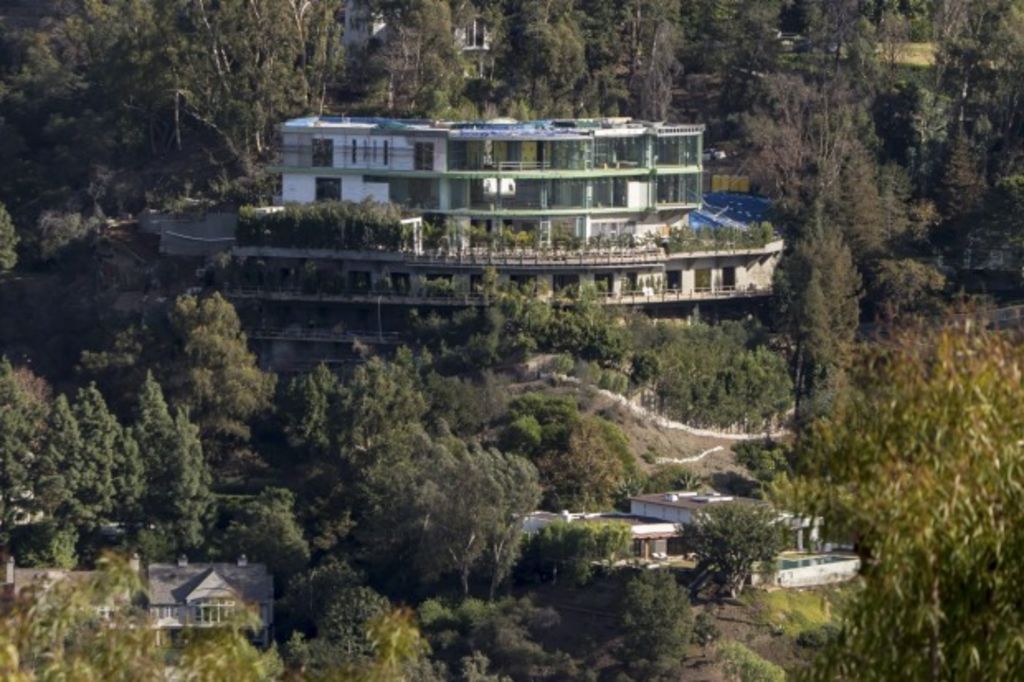

The most notorious new house in Los Angeles hangs from a Bel Air hillside, high above the sprawl and smog, unfinished and unloved.

Outraged neighbours call it “the Starship Enterprise,” and in truth it looks like nothing so much as an earthbound space station of curved glass and steel, draped in scaffolding and tarpaulin, roughly 2780 square metres and nearly 21 metres high.

That height, roughly twice the legal limit, is among a litany of violations that have stalled construction at 901 Strada Vecchia for more than a year. Without the city’s permission, workers tore down the original house and levelled the hillside. Though the site is in an “earthquake-induced landslide area,” subsequent inspections found “unsecured open excavations” and other perils. Inspectors also uncovered a host of features, unapproved though befitting a house with an aspirational price tag of US$100 million (AU$137 million) among them underground bedrooms and an IMAX theater.

It is as unapologetically extravagant as its impresario Mohamed Hadid, one of the city’s leading luxury developers. For years, Hadid’s Instagram account has featured photos of himself at the Bel Air site. He calls it his “office” and labels the photos with the hashtag #themodernhouseofhadid.

Yet for all that, over four years of violation notices, inspections and hearings, efforts to hold someone accountable for the mess at 901 Strada Vecchia have repeatedly hit a legal wall. It is, as a judge said during an October session where once again nothing got done, “an extremely complicated case.”

That is because “themodernhouseofhadid” belongs not to Hadid but to an entity that keeps the actual owner at a legal remove – a shell company named 901 Strada LLC.

Fuelled largely by the vast streams of wealth crossing the globe as never before, a new generation of hyperluxury homes with stratospheric price tags is colonising the most gilded hillsides and canyons of Los Angeles. In some areas, every third or fourth home has been torn down, leaving gashes of dirt and debris where new mansions will rise.

And more often than not, the people behind the purchases are hidden by shell companies.

LLCs were created to protect individuals from legal liability, and they have a range of legitimate uses.

Today in Los Angeles, as at 901 Strada Vecchia, LLCs have provided insulation – some would say impunity – amid a gathering anti-development backlash.

“That’s my – that’s the property I’m developing,” Hadid explained. “I’m the developer. I develop for other people.”

Law enforcement officials and anti-corruption groups worry that while many foreign buyers are simply seeking to safeguard their wealth in U.S. real estate, some are using shell companies to hide illicit gains, despite banking laws designed to flag the movement of large sums of money by foreign government figures, their families and close associates.

In Bel Air, an army of resistance has risen, a coalition of influential neighbours with their own considerable resources. Call it the haves vs. the have-even-mores, or perhaps the old (for LA) money vs. the new.

And while their bill of grievances extends to suspicions about shell companies hiding corrupt foreign money, what they talk about most is unethical and dangerous development – about dirt trucks run amok, the inevitability of mudslides and the waste of water in a time of drought.

“The person who is in control of the property has every interest in remaining invisible,” said James Spertus, a lawyer for the lawyer who is listed as 901 Strada LLC’s manager and who became a co-defendant when the city took the highly unusual step of filing a criminal case. “They’re not charged, and they want to stay that way, so there is no public record of that person.”

Joseph and Beatriz Horacek, who have documented construction activity at 901 Strada Vecchia, which looms over their property and is the subject of a neighborhood battle. Photo: New York Times

A Neighbourhood Battle

On Strada Vecchia, the neighbours tend to frame their cause as a campaign against the forces of greed.

It is not that they have not done well for themselves. Joseph Horacek III is a Hollywood lawyer; his wife, Beatriz, is a former bank compliance officer.

The Horaceks have made documenting the violations at No. 901 almost a part-time job.

The battle over the property, Joseph Horacek said, “started out as a matter of principle, then it got to the point that, ‘Oh my gosh, this is unsafe.'” They live directly down the hill, and they showed a reporter photos that appeared to show landslides.

In the interview, Hadid said he did not want to discuss accusations about his construction practices. But he did want to discuss neighbourly etiquette. His own neighbour, he said, has been doing construction for 11 years. Still, he said, “I never complain because I understand these complexities.” They come with the business.

Without naming names, Hadid said that the Strada Vecchia neighbours were “extortionists” and that they were the ones motivated by greed.

Joseph Horacek, for one, dismissed that, saying Hadid had offered him $2.5 million to drop his complaints but he had turned down the offer. It is not about money, he said.

Whatever the neighbours’ intentions, city officials say the project is in extensive violation of the building code.

The list of violations, in summary, goes like this: After the unapproved teardown and levelling of the hillside, the construction team did ask permission to grade the hill but used a survey that made it appear that workers had not already removed significant loads of dirt. Then they joined two buildings that were supposed to be separate and built so high that they drastically violated the city’s height limit.

The ambiguities surrounding Hadid and the ownership of 901 Strada Vecchia came to a head over the summer, as the neighbours pressed their case for legal action. At a hearing about the violations in June, several speakers pronounced themselves totally confused.

Documents trace a shifting trail of ownership over time.

After more than four years of violation notices, inspections and hearings, efforts to hold someone accountable for the mess at the property have repeatedly hit a legal wall. Photo: New York Times

Shifting Ownership

When Hadid purchased the property in early 2011, he put it in his own name and took out a loan through an LLC, with himself as “sole member/manager.” Early violation notices were addressed directly to Hadid.

But by the next year, the city was addressing notices to another shell company, Syntra Wva LLC. Hadid had sold the property at a below-market price to that LLC, which in turn resold it to another shell company, 901 Strada LLC.

As recently as spring 2014, Hadid signed a bank loan as “sole managing member” of 901 Strada LLC. And then there was the inspection this past spring, when Hadid “introduced himself as owner of the property,” according to Larry Galstian, the chief of inspections at the city’s buildings department.

As the legal process ground on, Hadid was, increasingly, steps removed from 901 Strada LLC.

At the hearing, a lawyer for the LLC made a point of saying, “Our client is not Hadid, who has been mentioned by name. Our client is an entity. It’s an LLC. Its managing member is here. He’s from Washington, D.C.”

That was a Virginia lawyer, James Zelloe, who is listed as 901 Strada LLC’s manager in its incorporation documents. The LLC’s phone number in city lobbying records is a recently disconnected cellphone for Zelloe.

When the city filed a criminal case in July, alleging a range of misdemeanour construction violations, Zelloe was listed as a co-defendant, along with the LLC.

Suddenly, the explanations began changing again.

Zelloe’s lawyer told The Times that his client was a mere functionary. “He has incorporated this property, as hundreds of attorneys do, but he doesn’t have any control or oversight of the property,” the lawyer, Spertus, said.

Calls to the LLC seeking comment were not returned.

The opacity of Hadid’s financing is one aspect of the project that the Horaceks, have emphasised in urging the city attorney to add Hadid to the criminal case.

Still, the central question remains: What will become of the unfinished behemoth up on the hill?

For all the criticism, Hadid said, “We are diligently working to finish this project under the supervision and approval of all necessary government agencies.”

The Horaceks, though, believe that the only way to bring the house into compliance is to tear it down.

Whether the city might eventually order that – and given the ambiguities of ownership, precisely whom it might order to do it – remains unclear.

But even with all of the case’s tentacles and mysteries, Joseph Horacek has hope.

“I think there is a chance we’ve opened up a piercing of the corporate veil,” he said.

This story was first published in the New York Times.

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More