The regional Australia towns where you're unlikely to ever be able to afford property

Once upon a time, there was the tale of a city slicker who, fed up with skyrocketing property prices in the capital, decided to cash it all in and head to regional Australia in search of cheaper housing and a less stressful mortgage.

There, the city slicker would live out their new, possibly debt-free or at least lower-leveraged life by the sea, or the trees – or both – and everyone would live happily ever after.

But that was before the pandemic hit.

Today’s city slicker is still fed up with skyrocketing property prices in the capital. They’ve risen by more than 20 per cent in 12 months. Thanks to protracted COVID lockdowns, there is even more incentive for the city slicker to flee to the regions of Australia.

But the dream of escaping a life of crippling debt outside of the capitals is no longer a given. Housing affordability has declined across the nation and, in some regions, to crisis levels. In fact, there are regions outside of the capital cities that are even more expensive than Sydney prices.

In the Byron region, the median house price is now $1.55 million, outstripping Sydney’s record-breaking $1.499 million median, on Domain data. Regions like Kiama and Wingecarribee are not far behind Sydney and are already more expensive than Melbourne, Brisbane and Canberra.

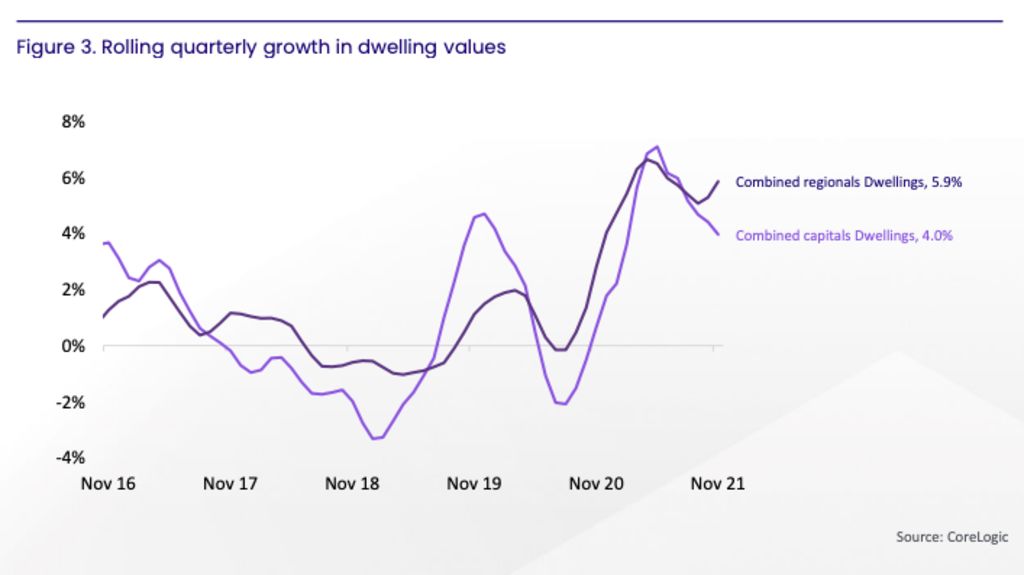

And CoreLogic’s latest home value index results indicate that prices across the regions show no sign of slowing just yet.

Over November, dwelling values in regional Australia increased a further 2.2 per cent, up from 1.9 per cent in the previous month, and at twice the monthly growth rate of the capital city markets.

This is unusual, according to CoreLogic head of research Eliza Owen.

“Unlike historic periods where a loss of momentum across the capitals was matched by an easing of growth in regional Australia, there is a clear divergence occurring across the two markets,” she said.

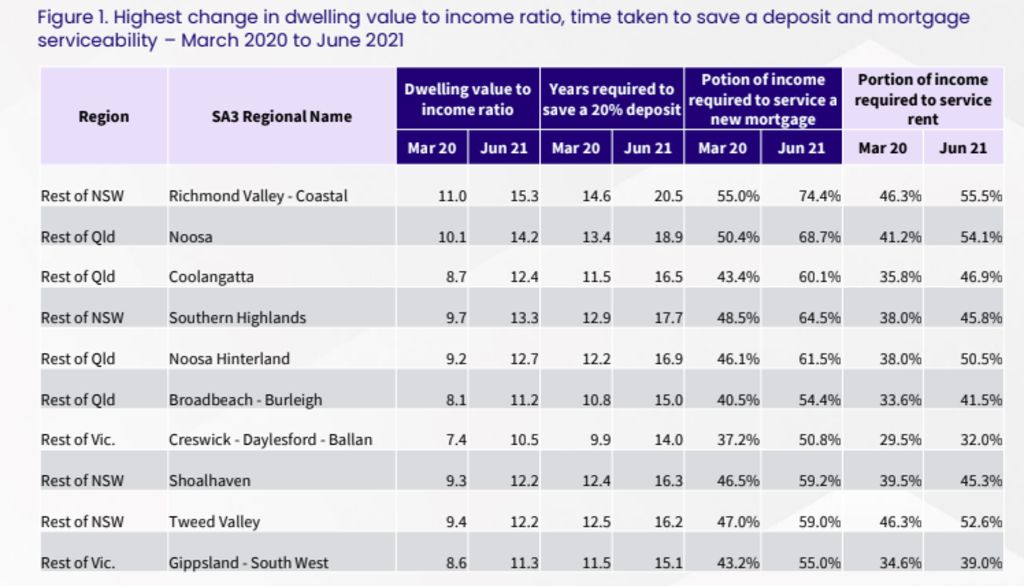

The recently released ANZ CoreLogic Housing Affordability Report showed widespread declines in housing affordability. At the national level, the ratio of housing values to household incomes reached a new record high in June, as did the number of years it takes to save a deposit, and the portion of income required to pay rents.

The report revealed particularly strained conditions for buyers in regional Australia.

It found that in the Richmond-Valley Coastal area, which includes Byron Bay, it now takes 20.5 years to save a 20 per cent deposit.

The analysis also found the portion of income required to service a mortgage there has hit a whopping 74.4 per cent.

In Noosa, it’ll take nearly 19 years to save for a 20 per cent deposit and then 68.7 per cent of a homeowner’s income to service the mortgage.

Other regions found to have massive affordability challenges included Coolangatta and Broadbeach-Burleigh on the Gold Coast, the Southern Highlands, Creswick-Daylesford-Ballan, Gippsland and Shoalhaven.

Ms Owen said affordability challenges in regional Australia had been exacerbated by the effects of COVID-19.

“Normalised remote work trends and appealing coastal or tree change settings became ‘pull’ factors of demand, while high capital-city property prices, and the higher incidence of strict social distancing restrictions, became ‘push’ factors, driving people away from major cities,” she said.

In the year to March 2021, migration from cities to regions increased 5.9 per cent, while the number of people leaving regional Australia for the capital cities declined 3.5 per cent in the same period.

“The combination of more people arriving in regional Australia and fewer people leaving for the cities has created additional demand for housing, pushing the number of homes available to buy or rent to extreme lows,” Ms Owen said.

It is important to note that many of the regional towns that are now likely out of reach for many Australians, city slickers or otherwise, were already expensive before COVID hit.

Ms Owen said this reflected a broader trend in the property market, where some of Australia’s richest suburbs have had the highest house price growth.

“Higher-value areas have tended to see higher annual dwelling value growth rates,” she said.

The question now is whether these elevated prices in Australia’s regional property markets are tenable in the longer term.

Previously sleepy regional towns have been swamped by newcomers. Demographics are shifting as quickly as house prices are soaring.

In Noosa Heads, where the median house price has risen by 23.3 per cent to $1.522 million in the space of just one year, serious money is pouring in, not from Sydney and Melbourne’s millionaires – every second person is one of those now – but from billionaires.

They’re over the hill at Sunshine Beach too, where Gina Rinehart reportedly shelled out $34 million for a house earlier this year. The median price there has gone up 46.7 per cent in 12 months to a record-breaking $2.665 million.

Frank Milat of Richardson & Wrench Noosa acknowledged Noosa had affordability issues.

“Twenty years ago if you bought an apartment in Noosa you’d be up to the bank and getting finance. Now, we’d be lucky to have 10 per cent of our buyers going to the bank. No one’s subject to finance anymore,” he said.

“The demographic has changed; they’re much wealthier, they don’t look at the numbers when they’re buying here, they look at their heart.”

Buying property in Noosa had become a much more difficult proposition for the average person mainly due to wealthy interstate buyers, Mr Milat said.

“Melbourne people call Noosa the northern-most suburb of Melbourne,” he said. “And when you get billionaires buying here, it has a ripple effect: people hear a billionaire has bought, they think, ‘It’s safe for us too’.

“They’re selling their $20 million houses in Sydney and moving up here and spending $5 million on the Noosa riverfront.

“Prices are going to keep going up – and we won’t get huge fluctuations because there’s a finite amount of supply. There are only five available properties for sale in Hastings Street right now – it’s not hard to get five buyers.”

CoreLogic research director Tim Lawless said there was a good chance Australia’s most unaffordable regions would remain unaffordable, and become more exclusive.

“However it’s reasonable to expect that values won’t rise anywhere near as much in 2022 as they have this year; partly due to natural constraints on affordability, but also the possibility of tighter credit policies and, eventually, higher mortgage rates,” he said.

“If demand remains high in these most popular regions, which is likely at least for the short to medium term, housing affordability pressures are set to worsen.

“The natural outcome of worsening affordability is that fewer people will be able to purchase or rent in these markets, which will naturally curtail housing demand and dampen price growth.

“The beneficiaries may be those more affordable adjacent areas considered as ‘next best’, with demand rippling north or south along the coastline or to the next suburbs along where prices are cheaper.”

Historically, many of these coastal and lifestyle markets have experienced greater levels of volatility in the past. The post-GFC period was a good example, when many of the coastal and lifestyle markets recorded larger than average falls in value as holiday-home owners looked to offload discretionary assets.

But Mr Lawless said the shift in demographic that had occurred in many of these regions, away from holiday investors to owner-occupiers, meant this no longer applied.

“These regional markets may be more insulated from that volatility now that more homes are owner-occupied rather than discretionary uses such as holiday homes or used for investment purposes,” he said.

For the city slicker to live happily ever after in the regions these days, they’ll either need deeper pockets to start with, or an open mind as to where they’re willing to go.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More