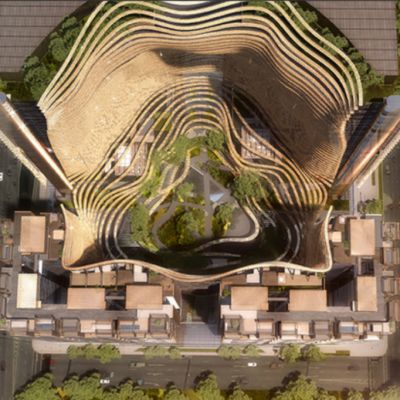

The Taiwan tower that will create a garden in the sky

In the nascent world of sustainable construction, architects are increasingly turning to high-tech solutions to limit the ecological impact. Take Tesla’s Powerwall and self-cleaning carbon-consuming roof tiles.

But not Vincent Callebaut. The Parisian architect has looked to nature itself to cure the ills of modern construction methods.

His Tao Zhu Yin Yuan project in Taiwan’s capital Taipei will feature 23,000 trees and shrubs so it can absorb 130 tonnes of carbon dioxide each year. Referred to by local media as the “city in the air garden”, the 20-storey building truly lives up to the notion of green building.

The ambitious design is focused on the welfare of not only its residents, but the massive amount of plants on board. To protect them from high winds and expose them to enough sunlight, the complex twists 90 degrees. The end result is an impressive spiral laden with suspended gardens.

Pollution is a major issue for the Taiwanese and has been the subject of recent public protests led by the country’s first Nobel laureate Yuan-Tseh Lee.

Lee, a chemist, called on Taiwan’s government to update pollution controls to improve air quality.

Callebaut’s twisting tower will be Taiwan’s greenest yet. It includes a variety of other eco-responsible measures such as solar and wind power facilities, glass insulation and rainwater storage.

While the project is admirable, John Doyle, RMIT architecture lecturer and director of NAAU architecture practice, says there’s a certain measure of ostentation.

“It’s an amazing feat of engineering and if it gets built, and I kind of hope it does, it will be an amazing piece of architecture but I’m not sure how much is being driven by sustainability values and how much is being driven by sheer shock value,” he says.

Developers and construction companies are currently guided by green star energy ratings or points systems, but Doyle says these processes don’t always guarantee a low-carbon emission build. Measuring carbon output needs to become a more precise science to calculate the true cost of construction.

“Basically every time a building gets built we need to take into account its energy consumption and that goes from even the smallest extension to the tallest buildings and infrastructure projects,” Doyle says.

“I think increasingly people are going to be directly thinking about carbon footprint and carbon calculation because green star ratings are often a little bit misleading so you can offset or you can get green star through things like car share programs which haven’t necessarily been quantified. A lot of particularly innovative architectural practices and engineering firms are not actually sitting down and working out the carbon footprint for the projects they build. It often reveals things you wouldn’t necessarily expect.

“In the case of the twisting tower, it can be more carbon intensive to put greenery on a tower just for the sheer weight of soil and water that need to be hoisted up, held there and supported through structure than it would be to, say for example to build it out of lightweight or reduced weight construction and offset that through other means or look at energy harvesting and things like that.”

The Tao Zhu Yin Yuan aims to consume the equivalent amount of pollution made by 27 cars each year.

The tower will house 42 luxury apartments including two penthouses. Residents will have access to a garage, indoor pool and fitness centre. Balconies won’t be the only home for plants, with hallway walls that continue the greenery theme.

Construction is expected to be completed by September.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More