Tighter lending conditions: Explaining the turn of Australia’s housing markets

The latest numbers are in – not only is the housing market downturn across Australia well underway, but the rate of decline is accelerating.

Sydney saw a steep drop over the quarter, with the median house price down 3.1 per cent ($36,000), the latest Domain House Price Report shows.

Melbourne’s median house price saw an even steeper decline of 3.9 per cent, or a $35,000 reduction over the quarter. In both cities units are now outperforming houses.

Nationally, house price falls were more subdued, down 2.6 per cent over the September quarter to $781,787.

But where did the downturn come from? One minute Sydney and Melbourne seemed bound for perpetual house price inflation, and next the (more colourful) headlines are reading “bricks and slaughter”.

Arguably the trigger had little to do with supply, migration or avocados. Instead, one of the most cited reasons for the tipping point has been “tighter lending conditions”.

As property owners on the east coast watch their equity decline, and buyers wonder whether they should enter the market, it is worth unpacking the importance of “tighter lending conditions” to the fall in house prices.

‘Tighter lending conditions’: What does it mean?

“Tighter lending conditions” basically means mortgages are becoming harder to get.

Certain mortgage products are becoming more expensive, maximum borrowing amounts are declining and more people are being refused loans.

This slows growth in the amount of credit available for housing, in turn lowering prices.

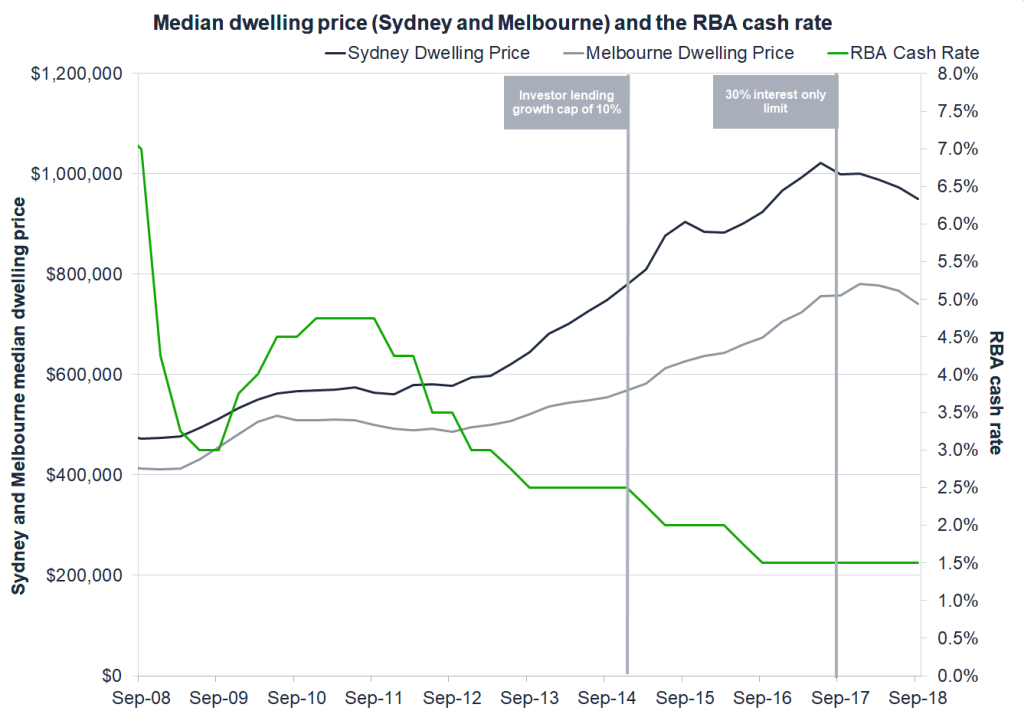

The above chart shows the interaction of the RBA cash rate, median metropolitan dwelling prices and institutional interventions. Cash rate cuts implemented in response to the global financial crisis serves to increase house prices. In 2014, APRA advised a 10 per cent growth limit on investment lending. As this virtually coincided with more cash rate cuts, prices continued to rise. However, after the enforcement of a 30 per cent limit on the portion of interest only loans, prices quickly responded.

How did we get here?

The Reserve Bank has been fighting two battles since 2012: sluggish economic conditions, and potentially risky lending.

Post-mining boom, a lower cash rate made the cost of money cheap, incentivising people and businesses to borrow, buy things and employ people. However, cheap credit also increased demand for housing, contributing to increased dwelling prices.

Between the round of cash rate cuts in 2012, and September 2018, Domain data shows median Sydney dwelling prices increased $370,000 (in nominal terms). Melbourne increased $250,000. The associated rise in household debt concerned the RBA.

Lending to investors was a particular concern, with cheap money potentially “encourage[ing] speculative activity in the housing market”. The combined value of mortgage lending for investment housing rose sharply above owner-occupied housing across NSW and Victoria.

This speaks to a major shift in Australian housing. By 2014, more money was being lent for housing as an investment, than as something for the owner to live in.

But with inflation and unemployment still not ideal, the RBA was not in a place to start increasing the cash rate to curb housing investment.

The 10 per cent limit on investor lending

In December 2014, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) – stepped in.

Chairman Wayne Byres wrote to major banks, advising that mortgage lending to investors should not grow above 10 per cent a year.

The letter implied if mortgage lending to investors exceeded a growth rate of 10 per cent, “supervisory actions” would be considered.

Banks complied with the recommendation by the September 2015 quarter. Even though this benchmark has since been removed, growth in investor lending has stayed low.

APRA also foreshadowed increases to bank capital reserves. Changes to borrower assessments were also made, to ensure borrowers could properly afford repayments.

Investor lending then slowed between 2015 and 2016, even sinking back below the value of loans to owner-occupiers in Victoria.

However, house prices continued to grow.

This is because, around the same time APRA set the growth limit, the RBA undertook four cash rate cuts. As money became cheaper, borrowing rose in the owner-occupier space.

Between the February 2015 rate cut, and the latest release of housing finance data, the annual value of new owner-occupier lending has risen 40 per cent in NSW, and 47 per cent in Victoria.

Stamp duty concessions for first home buyer owner-occupiers – introduced in 2017 – also encouraged an increase in lending.

The 30 per cent limit on interest-only lending

In March 2017, APRA announced another credit tightening measure.

This time, interest-only loans would be limited to just 30 per cent of new mortgages generated.

Interest-only loan terms mean the first few years of a mortgage only require interest repayments, rather than also paying down the principal.

Interest-only loans are popular with investors. APRA cites tax incentives as a motivating factor behind this. Negative gearing, for example, is more effective with an interest-only loan, because only the interest part of a mortgage is deducted from taxable income.

As a result, a cap on interest-only lending proved highly effective in targeting the investor sector of the market.

Banks had six months to meet this new requirement, and they responded quickly. The portion of new investors with interest-only loans funded fell from 67 per cent to below 40 per cent.

In the year leading to the 30 per cent cap announcement, investors comprised 56 per cent of the value of money being lent for mortgages in NSW (excluding refinancing). In Victoria they comprised 46 per cent.

The relationship between changes in investor lending and dwelling price growth is particularly strong in NSW. Hence it is likely that “tighter lending conditions” became a significant driver of dwelling declines.

Now mortgage rates are rising

The RBA cash rate is the most important benchmark for mortgage rates.

However, even as the official cash rate remains at a record low 1.5 per cent, mortgage rates have started to rise as bank costs increase.

A current pressure on banking costs is the ‘credit-deposit gap’: where banks face higher costs for credit, while receiving low interest repayments on outstanding loans.

This means that banks may need to pass on higher costs to existing or new mortgage holders. In other words, mortgage rates will rise.

While most banks have increased interest rates for mortgage products, not all mortgage products and customers are seeing the same increases.

Investors absorbed the largest interest rate increases. Interest-only loan rates for investors rose an estimated 100 basis points between 2015 and 2018. Principal and interest loans for investors rose 50 basis points.

Interest-only mortgage rates have also gone up for owner-occupiers by about 50 basis points.

More recently, banks raised rates for existing customers, while offering discounts for new customers in an attempt to increase market share.

Cheaper investor and interest-only loans could still be sourced from lenders that are not regulated by APRA.

Lenders unregulated by APRA only comprise a small part of the market — less than 5 per cent of outstanding housing credit — and have not had as large an impact on the housing market. However, unregulated banks’ share of credit has been growing over the past year.

A managed market downturn

The interventions of APRA have reduced the risk of speculative investment lending, and in turn have reduced house price growth.

The RBA has emphasised that while the supply of credit has been tightened, investor demand for mortgages has also slowed. APRA data reinforces this, showing the annual growth in investor lending actually peaked in June 2014, before the announcement of a recommended growth limit.

But even where the RBA has pointed out the role of declining demand, its own analysis showed that areas with high levels of rental stock had been relatively dampened by recent financial regulation.

Dampening investment and reducing speculation for an asset people live in is not a bad thing. Arguably, it should have been done years before their first intervention.

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More