Why are house prices rising when wage growth is low and unemployment is still high?

Swelling disposable incomes for some workers are helping push up property prices despite low overall wages growth and a high unemployment rate, experts say.

Falling interest rates are leaving potential borrowers better off than they would have been a year ago, while tax cuts in the recent federal budget are boosting take-home pay even for workers who missed out on a pay rise.

Those lucky enough to keep their jobs in the COVID-19 recession may have also saved on dining out during lockdown or on planned overseas holidays, boosting the size of their deposit.

House prices rose in every capital city, except Melbourne, where they were flat, over the September quarter, on Domain figures, adding 0.9 per cent nationally over the quarter. Apartment prices were mixed across cities but edged up 0.1 per cent nationally.

In October, home values – including apartments – rose in every city except for Melbourne where falls narrowed, according to CoreLogic.

Owner-occupier borrowers have been driving the price rises, with investors largely sidelined as inner-city apartment rents drop and international immigration stalls.

The strength of the housing market during Australia’s first recession in a generation has raised eyebrows, with ANZ this week scrapping its forecast for a 10 per cent house price drop as “too pessimistic” and predicting prices to rise next year.

This is despite official figures this week showing wages rose just 0.1 per cent in the September quarter, while the unemployment rate remains elevated at 7 per cent.

“It’s going to be hard for a worker to get a pay rise,” Commonwealth Bank head of Australian economics Gareth Aird said. “[But] what really matters to the end worker is what they see in terms of money going into their bank account.

“In the last three weeks most workers will have seen their pay packet go up because of the tax cuts.”

Although he warned the tax cuts were a one-off change compared to an annual pay rise, he noted someone on the average salary of $89,000 would take home an extra $1080 a year, a 1.6 per cent annual increase in take-home pay.

He estimates by early 2021 households overall will have built up additional savings of $100 billion since the start of the pandemic, excluding early superannuation withdrawals, because of government stimulus and less spending due to restrictions.

Those in work might use extra savings towards a house deposit, he said, while also paying less on their mortgage as interest rates fall.

Ultra-low interest rates mean someone with a deposit and a job can enjoy lower repayments than this time last year, even as prices lift.

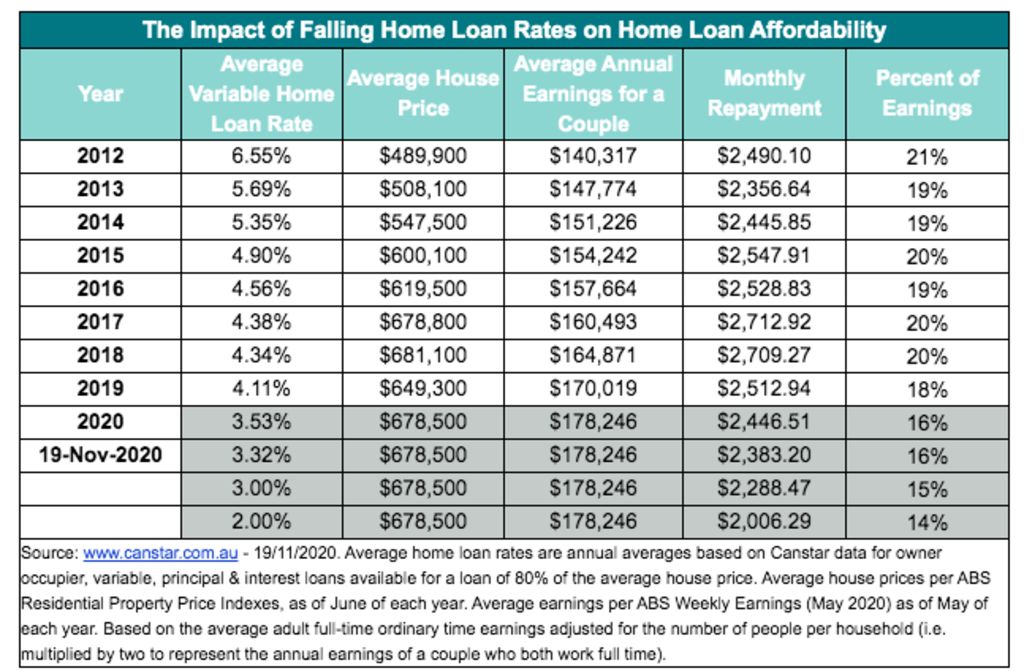

An average couple buying an average house now would spend only 16 per cent of their monthly earnings on mortgage repayments, compared with 18 per cent a year ago and 20 per cent the previous year, a Canstar analysis shows.

It assumes the couple’s combined annual earnings are $178,246 and they buy a property at the national average price of $678,500, on ABS figures, with the average variable home loan rate of 3.32 per cent. Their monthly repayments would be $2383.20.

A year ago, the couple would have expected to spend $29,200 less on the same house with a combined income about $8000 lower, but pay an extra $129.74 in monthly mortgage repayments – cash they can now keep.

“People are saying that with interest rates this low, we’ve really got to get in and spend some money on property at this point,” Canstar group executive of financial services Steve Mickenbecker said. “There’s a huge amount of stimulus being plugged into the economy.

“With all of that stimulus people are immediately reacting and saying, ‘we’re going to see a bit of a property boom over the next couple of years’.

“I suspect FOMO [fear of missing out] is beginning to creep back into the psyche.”

Although lenders would not be surprised if a home loan applicant was not getting pay rises, they would check the security of their income and whether it was from a permanent or contract job, he said.

Banks would also want to see a track record of saving, a lid on spending, the ability to afford repayments and either a substantial deposit or an equivalent such as the federal government’s First Home Loan Deposit Scheme that allows buyers to get into the market with a low deposit and avoid lender’s mortgage insurance.

Another reason why house prices have risen in the recession is that job losses have been concentrated among workers least likely to be buying houses.

BIS Oxford Economics chief economist Sarah Hunter said the job losses this year have disproportionately been borne by low-income earners, casual workers and second jobs.

“[There are] quite a few people out of work but the vast majority of people are not – they are still employed even if their wages haven’t gone up,” she said.

“Those job losses and people on those casual, temporary contracts – they’re not typically owner-occupiers.”

Despite all the stimulus, including pre-covid cash rate cuts, at some point weak wages growth could act as a constraint on the housing market, she said.

“If in a year, two years, wages haven’t moved, that will act as a brake on price rises,” she said. “Prices can’t outpace incomes forever.”

ANZ senior economist Felicity Emmett said the jobs market had been affected in a “divergent” way.

“If we look at the highest paid occupations, we know that jobs have risen in those occupations through this period,” she said.

“There’s a significant cohort of people out there who have secure employment and are in in a position to take advantage of these really low interest rates.

“When you look at the bottom fifth of wages, those occupations have been the hardest hit, hospitality, arts and recreation.”

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More