Will Australia's property market ever go backwards?

Australia’s property market has been full of surprises over the years, always doing the unexpected despite the odds – like a boom during a cost-of-living crisis and heightened interest rates.

The latest surprise is Melbourne’s market going backwards at the same time as most other capital city markets reached new price peaks.

However, as far-fetched as it may seem in this current environment, is it possible for Australia’s entire property market to go backwards? What would need to happen for this to be replicated in other capital cities?

PRD real estate chief economist Dr Diaswati Mardiasmo says it’s essential to define the meaning of “backwards”.

“If you’re expecting [property prices] to go back to pre-COVID times, then that’s unrealistic. The likelihood of that happening will be quite low,” she says.

“But if you’re saying that, maybe prices can go back by $20,000 or 10 per cent or something like that, then the possibility of that is much higher than thinking that there’s going to be a crash.”

The difference between a market crash and the market going backwards

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver says if property prices fall by more than 20 per cent, it’s considered a crash. If this happened across all Australian property markets, it’s called a market crash.

“However, [the Australian property market] hasn’t seen deep falls. The most was like 15 per cent in Sydney in the 2015-17 period,” he says.

While a property market crash would lower prices, it also usually comes off the back of a suffering economy.

“Seventy per cent of Australian household wealth is tied up in the residential property market. For a crash to happen, the broader economic impacts would be vast,” says Domain chief of research and economics Dr Nicola Powell.

Among those impacts would be higher unemployment, instead of the current 4 per cent. For reference, during the global financial crisis, when the US property market suffered a crash, its unemployment rate was 10 per cent.

“It is hard to imagine a crash, particularly given we have such an undersupply of housing,” says Powell.

Other economic factors that can precipitate a market crash are a massive slowdown in population growth and high interest rates, Oliver adds.

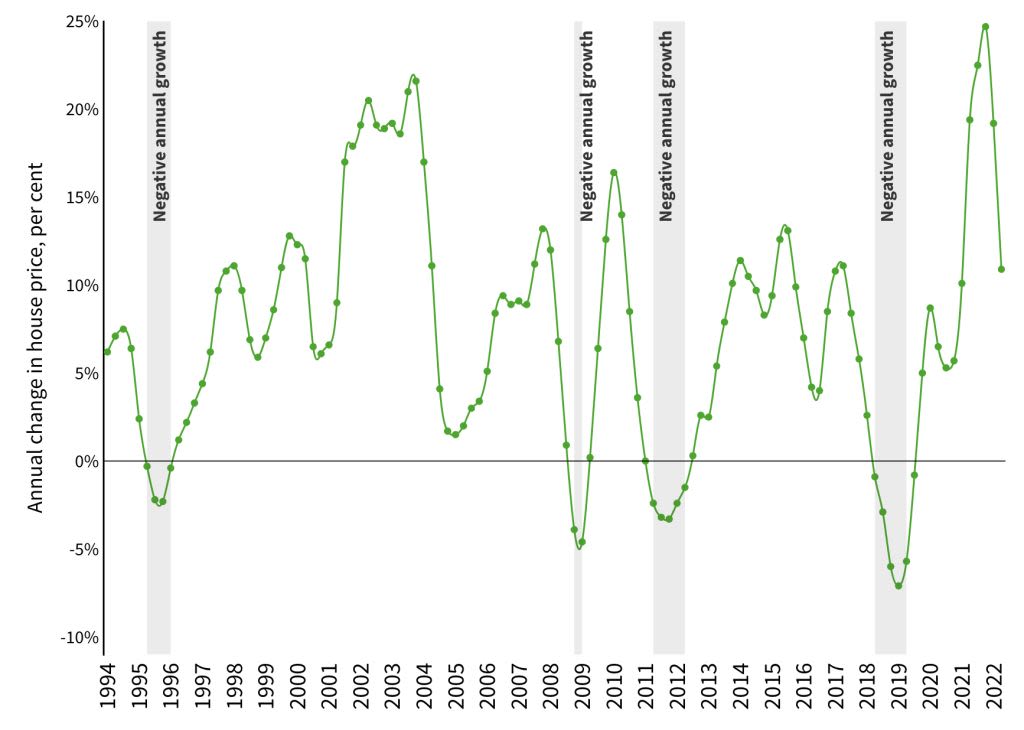

However, the property market going backwards (or weakening) is part of the usual price cycle.

“It’s not a bad thing. You could argue it’s a healthy thing,” says Oliver.

“A property market cool down gives an opportunity for home buyers who might have been squeezed out to get in; remove some of the under-affordability. A pullback would be seen as normal.”

Another phrase for a market going “backwards” is a downturn. Historically, on average, house prices see a decline of 3 per cent from the price peak, according to Domain data.

Why have Melbourne’s property prices fallen?

Powell calls Melbourne a “real anomaly”.

In the last quarter, Melbourne’s house prices slipped by 1.5 per cent on Domain data.

“It has been so unusual in terms of its performance, and I would describe it as having pretty much gone sideways,” says Powell.

“We’ve seen the Melbourne housing market go sideways for the last 18 months. For the next 12 months, we expect prices will continue to go sideways. So, that’s like a two-and-a-half-year period in which Melbourne property prices have done nothing.”

Powell says the current perception of Melbourne’s market is negative, but she believes it shouldn’t be.

“More subtle rates of growth are what you want coming out of a property market. You don’t want big periods of an upswing or equally big periods of a downturn. This subdued upward movement in price is a better outcome for housing affordability and people trying to break into the market.”

Why aren’t prices falling in other markets?

There are three key differences that explain why other capital city markets are outperforming Melbourne, says Powell.

“Overall supply has been much better, so there’s much more choice on the market, which means there’s less urgency.

“Population shifts have weighed on housing demand in a negative capacity. Population dynamics are still not back to what they were pre-pandemic.

“Thirdly, one of the bigger reasons is taxation and land tax changes. Not only are investors looking at Melbourne and going, ‘well, land tax is higher’, they’re also saying ‘I’ve also got no prospects of capital growth in the short term. I’m going to go elsewhere’,” she says.

| Land Value | 2023 Land Tax General Rate |

2024 Land Tax General Rate |

| Less than $50,000 | Nil | Nil |

| $50,000 to < $100,000 | Nil | $500 |

| $100,000 to < $300,000 | Nil | $975 |

| $300,000 to < $600,000 | $375 plus 0.2% of amount > $300,000 |

$1,350 plus 0.3% of amount > $300,000

|

| $600,000 to < $1,000,000 | $975 plus 0.5% of amount > $600,000 |

$2,250 plus 0.6% of amount > $600,000

|

| $1,000,000 to < $1,800,000 | $2,975 plus 0.8% of amount > $1,000,000 |

$4,650 plus 0.9% of amount > $1,000,000

|

| $1,800,000 to < $3,000,000 | $9,375 plus 1.55% of amount > $1,800,000 |

$11,850 plus 1.65% of amount > $1,800,000

|

| $3,000,000 and over | $27,975 plus 2.55% of amount > $3,000,000 |

$31,650 plus 2.65% of amount > $3,000,000

|

Mardiasmo says for the different markets across the country to go backwards or experience something similar to Melbourne, they would need “a much bigger shock” to the economy.

“We would need an event where we are shut down, economy-wise, for quite some time the way Melbourne and Sydney were [during COVID-19],” she says. “When I say quite a while, I’m not talking just two or three weeks.”

Cities like Brisbane and the Gold Coast, which saw strong rates of growth during a global pandemic, would need to suffer a massive financial crisis and go into an economic recession to see a big dip, says Mardiasmo.

Unlike Melbourne, other cities have a supply problem, and the demand will keep pushing prices up despite high inflation, high cash rates and weak economic growth.

“Our supply is probably about three, four years behind. And so it is about slowing down that demand,” says Mardiasmo.” [For prices to drop significantly] it really needs to be a big enough event to reduce demand significantly.”

Will the Australian property market ever go backwards?

Many economists agree that the Australian property market is unlikely to return to pre-pandemic prices and is highly unlikely to crash unless something catastrophic were to happen to the Australian economy.

“The old saying in Australia used to be ‘the property market never goes down’,” says Oliver. “There’s a bigger constituency that wants higher property prices than lower prices.”

We recommend

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More