‘Worse before it gets better’: Renters face stiff competition for homes

Australian tenants are struggling to find affordable homes, as strong demand and fewer rental options drive up competition and prices for properties.

Tenants are facing record low rental vacancies – fewer than 1 per cent of rentals were left empty in August – and experts fear the situation could worsen in the months ahead.

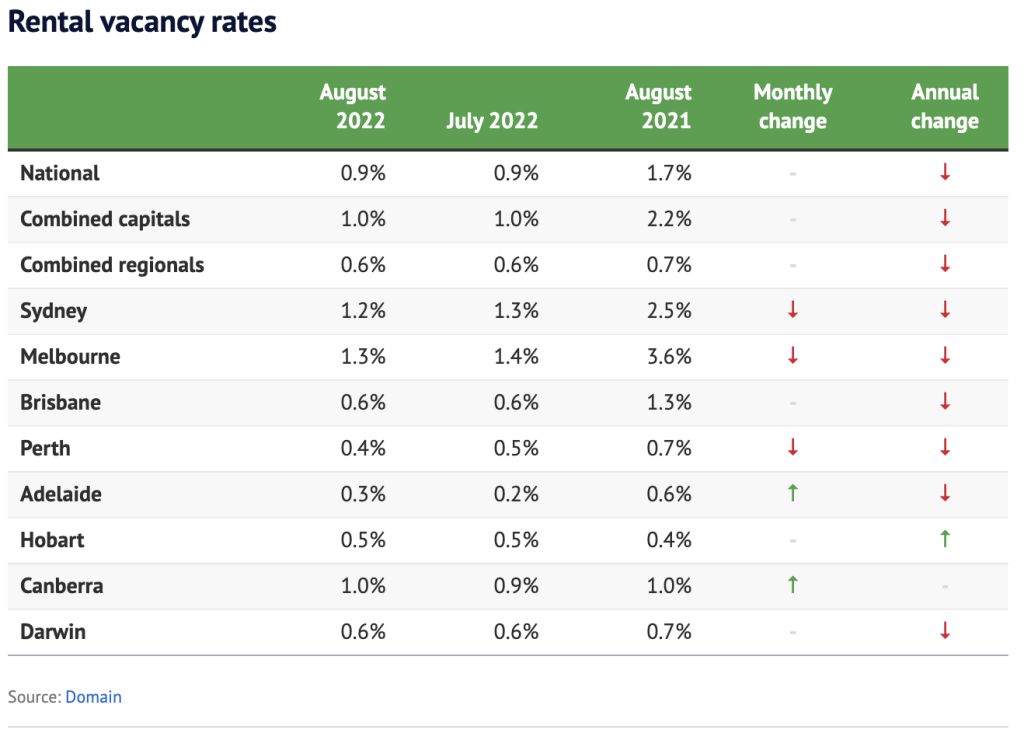

The national vacancy rate held at 0.9 per cent last month, down from 1.7 per cent the previous August, Domain data shows, and the proportion of empty rentals in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane more than halved year-on-year.

Sydney’s rental vacancy rate fell to 1.2 per cent, the lowest on record for the time series, which began in 2017. Melbourne’s rate dropped to 1.3 per cent, marking the eighth consecutive monthly decline and lowest point since March 2019.

Vacancies fell to a record low of 0.4 per cent in Perth, and held at a low of 0.6 per cent in Brisbane. The rate held steady in Hobart (0.5 per cent) and Darwin (0.6 per cent), and increased slightly to still-tight levels in Canberra (1 per cent) and Adelaide (0.3 per cent).

Just 0.6 per cent of rental homes across regional Australia were vacant.

Brendan Coates, economic policy program director at the Grattan Institute, said demand for rentals increased during the pandemic, despite the halt in population growth, as Australians sought more living space.

“The average household size has fallen, and the Reserve Bank estimates … this has added demand for an extra 140,000 homes, offsetting the fall in population growth,” he said.

The reopening of borders, and rebound in international student numbers, was adding to rental demand, Coates said. An increase in the number of permanent skilled migrants to a record 195,000 places this year, in a bid to tackle the jobs crisis, would further add to demand, and could drive vacancies lower.

More homes would be needed to support increased demand, Coates said, but with only about 2 per cent of the nation’s housing stock built each year, the situation for tenants was “likely to get worse before it gets better”.

Raine & Horne head of property management Maria Milillo, who is herself a renter, said tenants were desperate to find suitable housing, and more were staying in properties that no longer suited their needs due to a lack of stock.

Tenants were offering to pay rent months in advance, sign longer leases, and pay more than the advertised rate to try to secure a rental in the competitive market, Milillo said, but noted this was not encouraged by property managers.

“It’s competitive across the board. I was chatting to a friend yesterday who leased a property in the Sutherland Shire, she offered six months’ rent upfront. People know … there needs to almost be an incentive to get yourself across the line,” she said.

Many good applicants were missing out on homes, she added, due to the shortage of rentals, which had been exacerbated by landlords cashing out during the market boom.

Rent hikes of $100 or $200 between tenancies were common in some areas.

Tenants Victoria director of community engagement, Farah Farouque, said renters on low to middle incomes – including a growing number of young families – were facing the greatest challenge, with rent hikes truly outstripping growth in wages and support payments. Even once-affordable outer suburbs and regional areas were becoming too expensive.

“We’ve had a surge in people talking about financial stress from rent increases varying from $30 per week to up to $320 per week in one very stark case,” she said.

Even those with a good savings history and referees were struggling to find a modest home, she added. Some were forced to move towns, including a woman in her mid-50s who resorted to a room in a share house two hours away.

“We’re seeing this story replayed in many towns and suburbs across Victoria right now,” she said.

Tenants’ Union of NSW chief executive Leo Patterson Ross said the state of the rental market was “a disaster”. Rents and no-grounds evictions were rising, and some tenants who were evicted were struggling to find a new property in time.

“We’re hearing from people with 100-plus applications in,” he said, adding the application process for homes was also becoming more intrusive, as some tenants were asked to provide links to their social media profile.

“Given the job summit [last week], this inability to make sure that people have houses that are good quality, that are near their employment, is something that we really need to get a handle on because it is affecting people’s ability to maintain employment,” he said.

“We need to recognise housing as an essential service … and where the private market won’t supply houses that are available and affordable, then the government needs to step in.”

Both Coates and Farouque also called on the governments to do more to boost housing supply, particularly social and affordable housing, and wanted an increase to Commonwealth Rent Assistance. Farouque also called for the Victorian government to look to limits on rent increases.

We recommend

We thought you might like

States

Capital Cities

Capital Cities - Rentals

Popular Areas

Allhomes

More